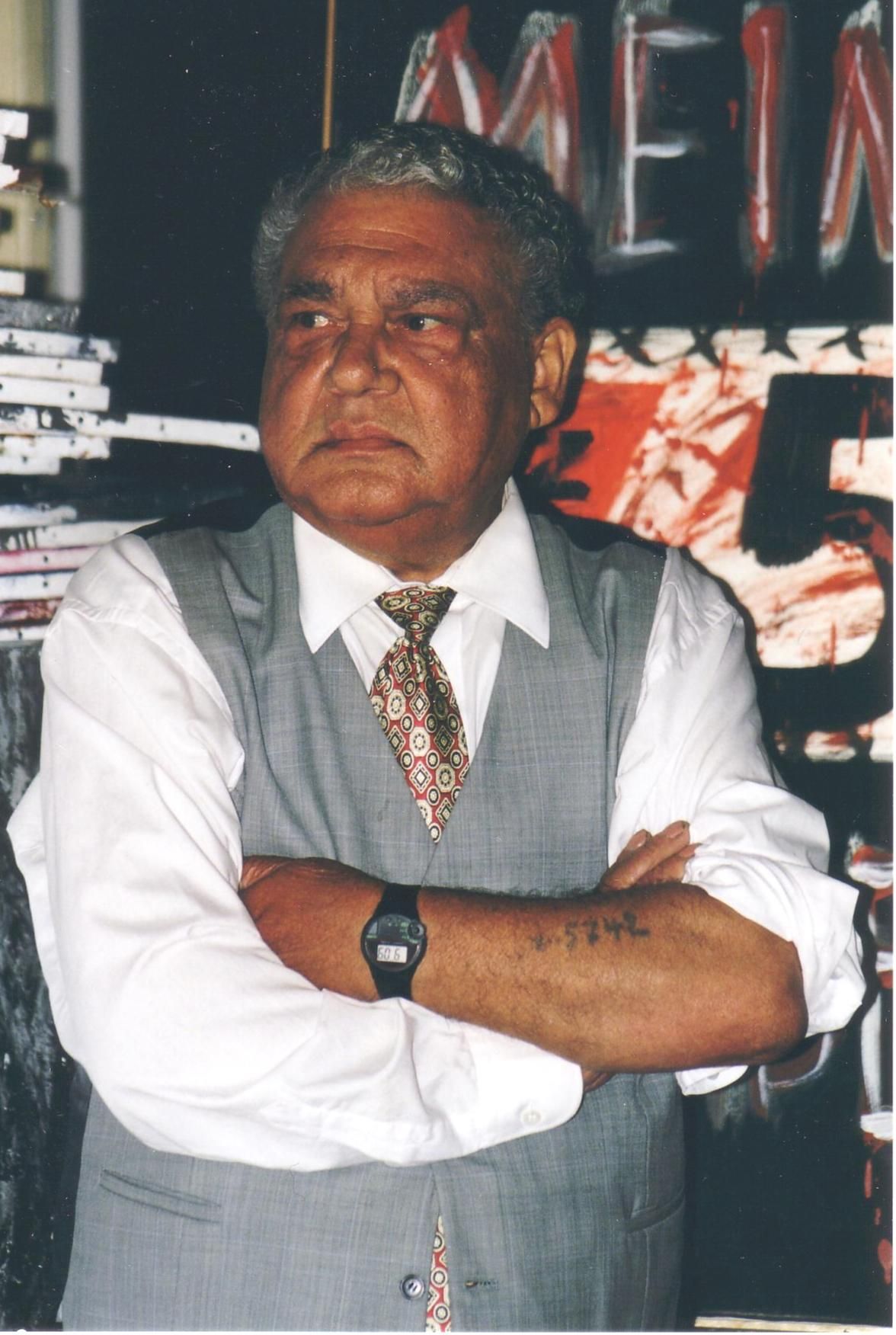

Karl Stojka

(Wampersdorf 1931 – Vienna 2003): Roma survivor

“Help, my God, what have these people done to us?”

The story of the Stojka family has already been described in the portrait of Karl Stojka’s sister Ceija. Karl Stojka decided late in life to start appearing as a contemporary witness, and above all to capture the images in his memory in paintings. There is an interview by Karl Stojka for the Shoah Visual History Foundation initiated by Steven Spielberg, which is unsettling in its intensity and gives a deep insight into the abysses of survival. He remained resistant in his own way and narrated in a unique manner that confirmed, confounded and contested clichés. They had moved around like nomads; the Lovara family had traded in horses, their mother had also been a fortune teller. Of course, she had stolen chickens from the farmers, they had known it too, saying: “Oh no, the gypsies are coming. Hide the washing and the chickens and the children.” Karl Stojka strongly denied the stereotype that children were stolen, since there were enough children in the families like his, with six siblings.

Karl Stojka describes dramatically how his father was taken away and interned in the concentration camp and how, later on, a package arrived containing his belongings such as a suit, shoes, shirt and also ashes and bones. As a deeply religious Catholic, his mother had wanted a Catholic funeral, which was actually not legal because of his cremation. Nevertheless, the priest lent her his support. With her hands, and with the priest’s blessing, his mother buried the ashes, the bones and her own hair, which she had cut off. The young Karl could not understand this and hoped to find his father again on the street. In 1943, the Gestapo took him out of school and brought him to the Rossauer barracks. He was deported with his family to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Crammed into the wagon, the small children died first, then the old and the older children. The children cried out in vain: “We’re thirsty, so thirsty, we’re so hungry and thirsty.” He described it unabashedly: “...the shit just ran down us, we pissed on ourselves, we crapped ourselves. It all just ran down us, the excrement and the dirt. And there were the dead. Help, my God, what have these people done to us?

He, too, describes how his little brother Ossi died of typhoid fever in the Auschwitz-Birkenau gypsy camp, the miracle that all the others survived, then how he was separated from his mother and sisters, survived the concentration camps in Buchenwald and Flossenbürg, and, finally, the death march. He was friends with Viennese Jews, and they saved each other’s lives, so the story goes. His friend Fredl could no longer walk: “And then I took him on my back and dragged him a few metres. Then it was Fredl’s turn to help: “Those Jews saved my life, because once I couldn't walk any more, they dragged me, on my back.” When Karl Stojka saw an American tank on the death march, he fantasised that the tank driver was God: “Thank you, God, that you’re finally here, thank you, Lord God.” The tank driver just waved and said kindly, “Go, go, go.”

Remembering was a burden for Karl Stojka, as it was for many other survivors. In the interview, Karl Stojka suffered and was completely exhausted by the fact that he could only recount so few of all the terrible things. Like others who remembered, he knew that he would not be able to sleep for nights on end afterwards: “Because then I’m there... I fall asleep and I am at Auschwitz again or Birkenau. Why is that possible?”

Incidentally, Austria’s cultural landscape has benefitted in many ways from the survival of the Stojkas. Karl Stojka’s son is the legendary jazz guitarist Karl Ratzer, the son of Karl Stojka’s brother, Johann Mongo Stojka, is the guitarist Harri Stojka.

Literature

Gerhard Grassl (ed.), Karl Stojka. Nach der Kindheit im KZ kamen die Bilder, Vienna 1992.

Karl Stojka, Mein Name im Dritten Reich: Z 5742, Vienna 2000.

Karl Stojka, Wo sind sie geblieben …? Geschunden, gequält, getötet – Gesichter und Geschichten von Roma, Sinti und Juden aus den Konzentrationslagern des Dritten Reiches, edited by Sonja Haderer-Stippel, Oberwart 2003.

Mongo Stojka, Papierene Kinder. Glück, Zerstörung und Neubeginn einer Roma-Familie in Österreich, Wien 2000.

Karl Stojka, Interview 43.504. Visual History Archive. USC Shoah Foundation. Transcript Freie Universität Berlin. 2012: http://www.vha.fu-berlin.de (23.3.2015).