About the Exhibition

The new Austrian exhibition in Block 17 of the State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau bears the title “Far Removed. Austria and Auschwitz”. The notion “far removed” refers to the geographical distance between Austria and Auschwitz, which was part of the Nazi strategy to conceal the genocide. At the same time, removal was synonymous with extermination: it meant the physical removal of the deportees – from Austria and from the realm of the living.

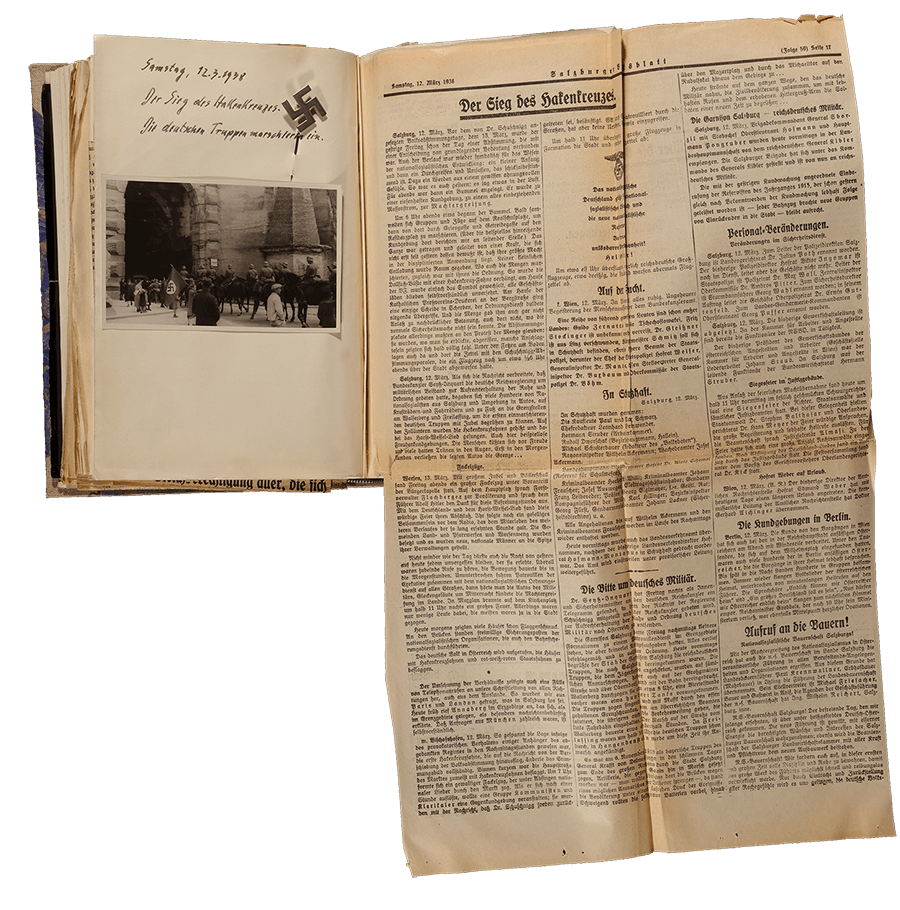

Nazi Germany’s annexation of Austria and Adolf Hitler’s march into his former homeland in March 1938 were greeted with widespread euphoria. The event is commonly known as the “Anschluss”.

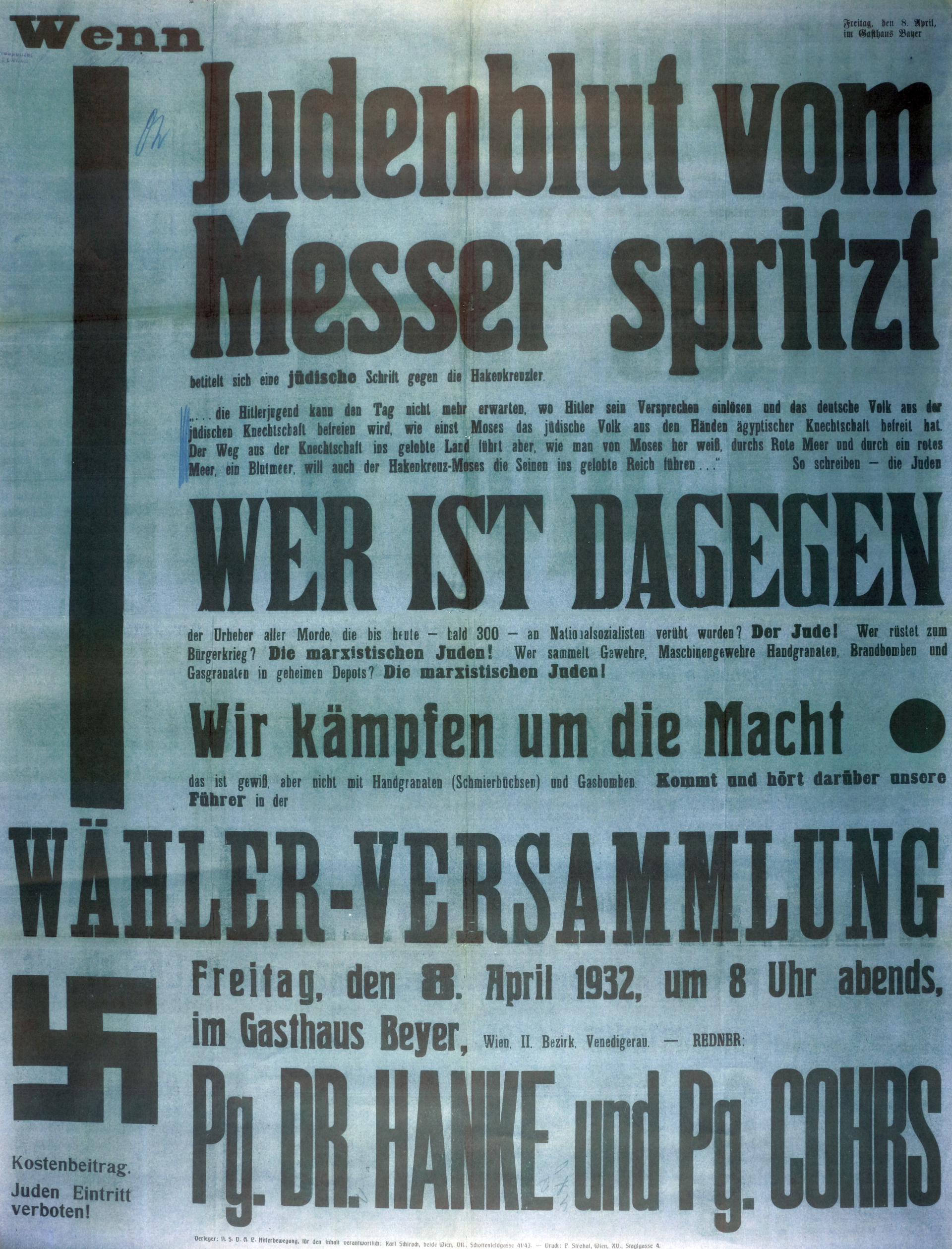

In terms of ideology, the Nazis were able to count on deeply entrenched antisemitic beliefs: racial antisemitism rooted in centuries of anti-Jewish sentiment had formed a part of daily social and political life since the late 19th century.

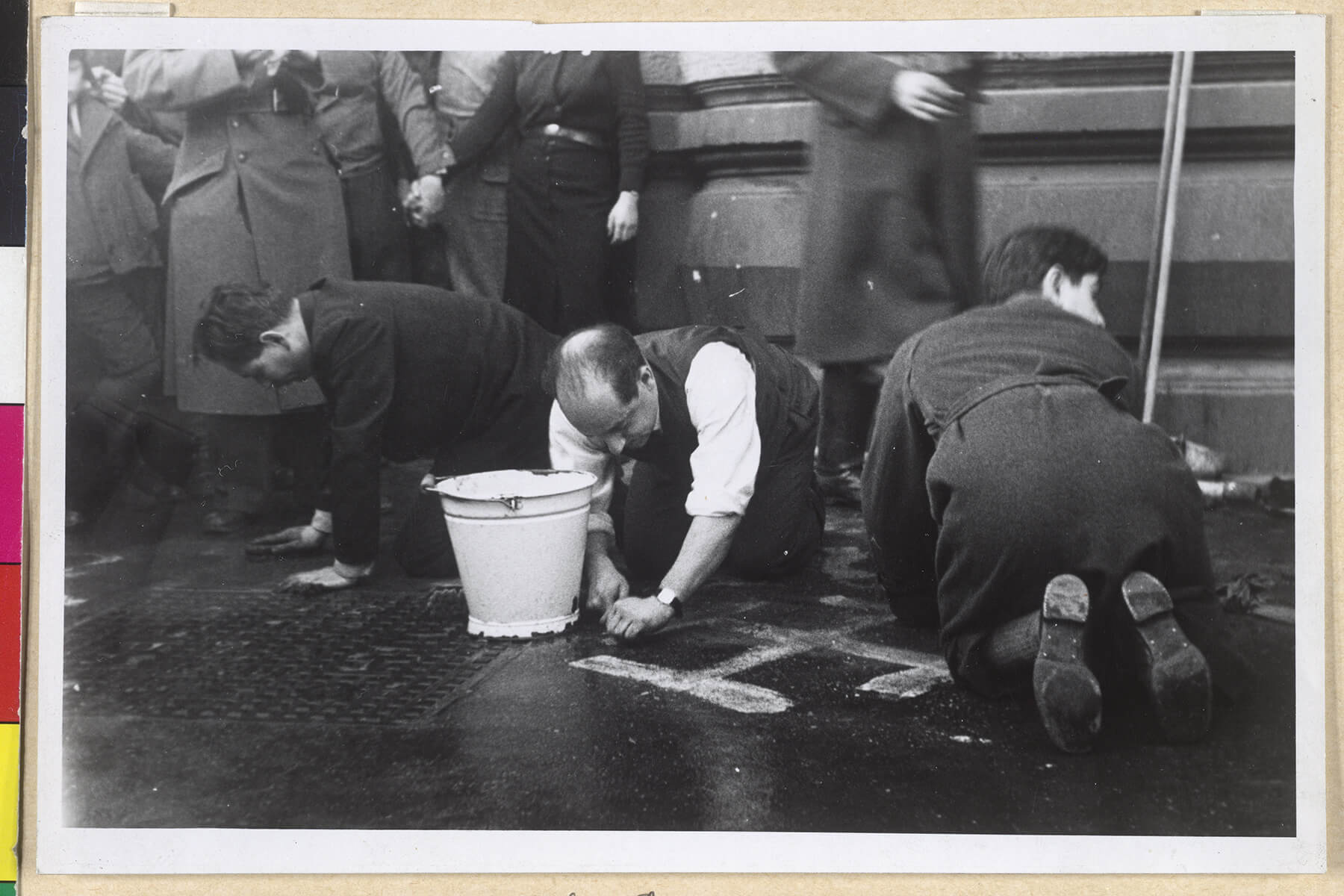

The months following March 1938 were characterised by repeated outbreaks of antisemitic violence, which were similar in nature to pogroms and received broad popular support and approval. Jews were forced to scrub the roads and pavements to remove political slogans calling for Austrian sovereignty and denigrating Nazism. This took place in public as a gloating audience looked on.

In spite of this, after 1945 Austria perceived itself as the “first victim” of the Nazi regime. This perception, which negated Austria’s shared responsibility for Nazi crimes, continued to be perpetuated for many years and only started to be gradually revised from the 1980s onwards.

Hostility towards Jews and anti-Jewish stereotypes and prejudice had been rife in Austria since the Middle Ages. Even at that time, financial chicanery had given rise to pogroms that were then justified by false allegations against the Jews (such as ritual murder, desecration of the Eucharist, poisoning wells). The Church viewed the Jews as the murderers of Christ and, consequently, it was the driving force behind the propagation and perpetuation of anti-Jewish sentiment.

With the advent of early capitalism, the claims made against the Jews also evolved. Usury, a term generally used to mean the taking of interest, became an accusation levied against Jews within the context of anti-capitalist criticism. The Jews were increasingly equated with big business, even though the majority made a living from the small-scale trading of goods and not from the money lending business. Pre-modern era hostility towards Jews was ultimately aimed at converting Jews to Christianity. Ever since Martin Luther, it had been a subject of debate whether there was an innate “Jewish nature” which could not be overcome through baptism.

The Enlightenment laid the foundation for the integration of the Jews, but only for those who were of economic benefit to the state. The equal rights demanded for the Jewish population in the course of the revolution of 1848/49 for were finally achieved in 1867. At the same time a new form of hostility towards the Jews began to proliferate: racist antisemitism. This built on “traditional” hostility towards Jews, integrated it into the modern science of race studies, and turned the familiar stereotypes into “scientifically quantifiable” characteristics of a “Jewish race”.

From the late 19th century onwards, antisemitic ideology permeated all classes of society. In Austria it was first seized on by the Christian-Social mayor of Vienna, Karl Lueger, and, later on, by all political parties to varying degrees. The Nazis placed racist antisemitism at the centre of its political agenda, which culminated in the expulsion and annihilation of European Jewry.

The “Anschluss” of Austria to the German Reich and the subsequent introduction of the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 had far-reaching consequences for the Jewish population, who were progressively stripped of their civil rights. The weeks following Adolf Hitler’s march into his former homeland were marked by pogrom-like riots against the Jewish population: Jews were forced to scrub Austrofascist slogans denouncing the “Anschluss” from the streets in so-called scouring actions as a largely gloating crowd looked on. Jewish shops were defaced, looted and destroyed.

The “Anschluss” of March 1938 saw the Austrian people divided into two groups: those who “belonged” and those who were excluded from society from that time on. Those who belonged ranged from people who supported the regime through silent complicity, to those who played an active role in the crimes of the Nazi regime. The other group, the excluded, included political opponents, Jews as defined by the Nuremberg Laws, Roma and Sinti, Jehovah's Witnesses and people deemed by the Nazi system to be asocial, homosexual, criminal or professional criminals, as well as those with hereditary illnesses or considered “unworthy of life”.

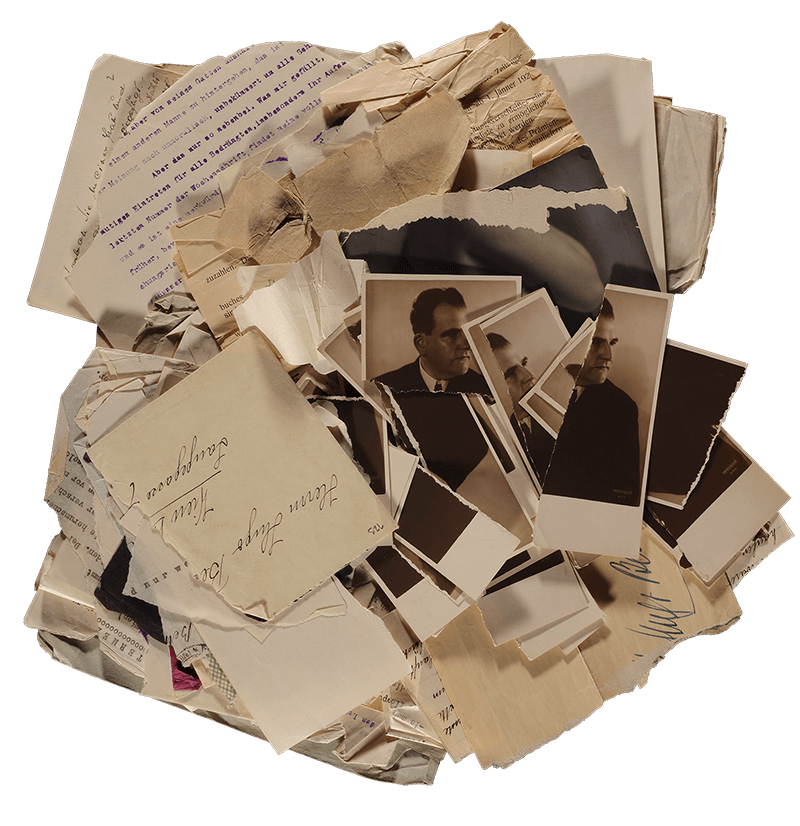

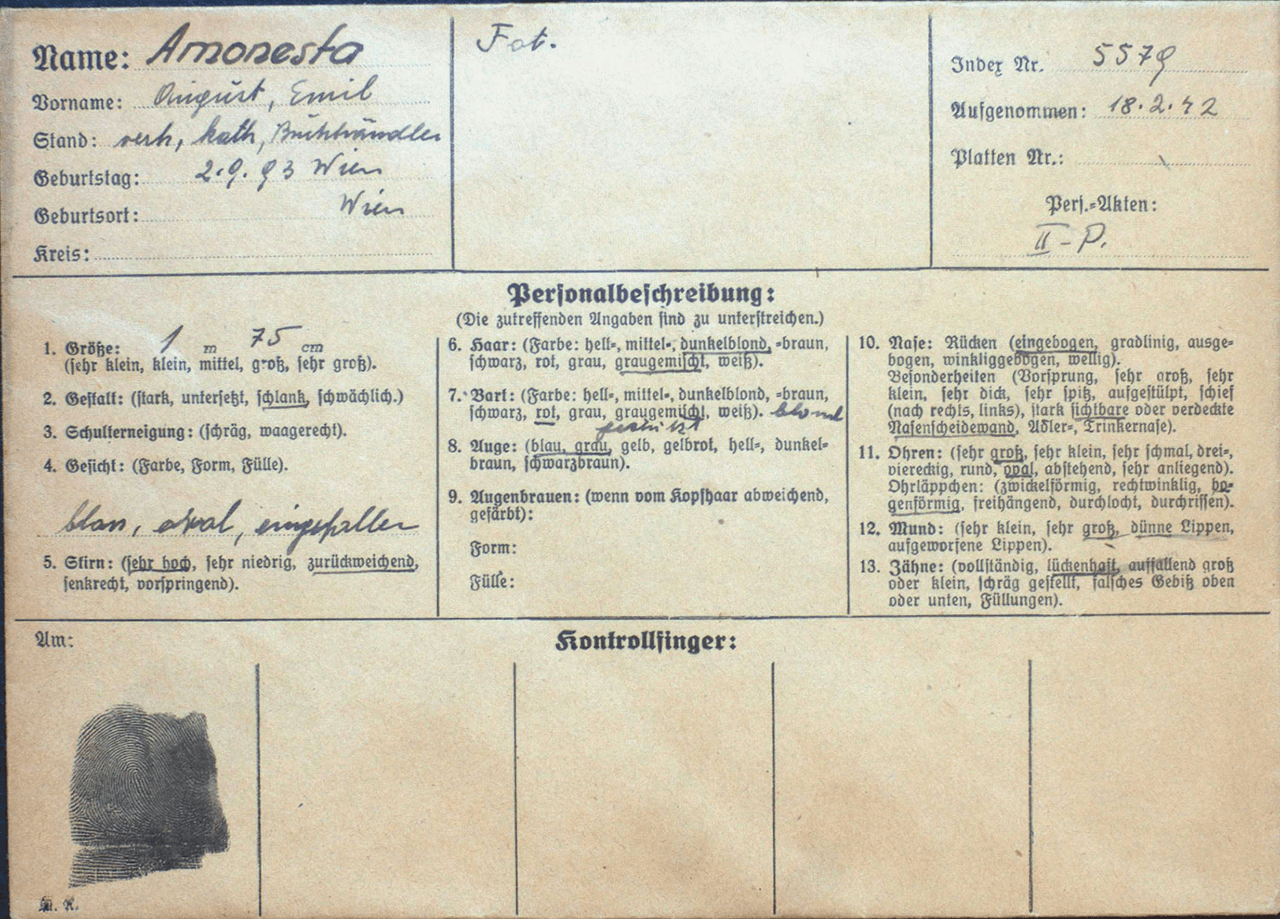

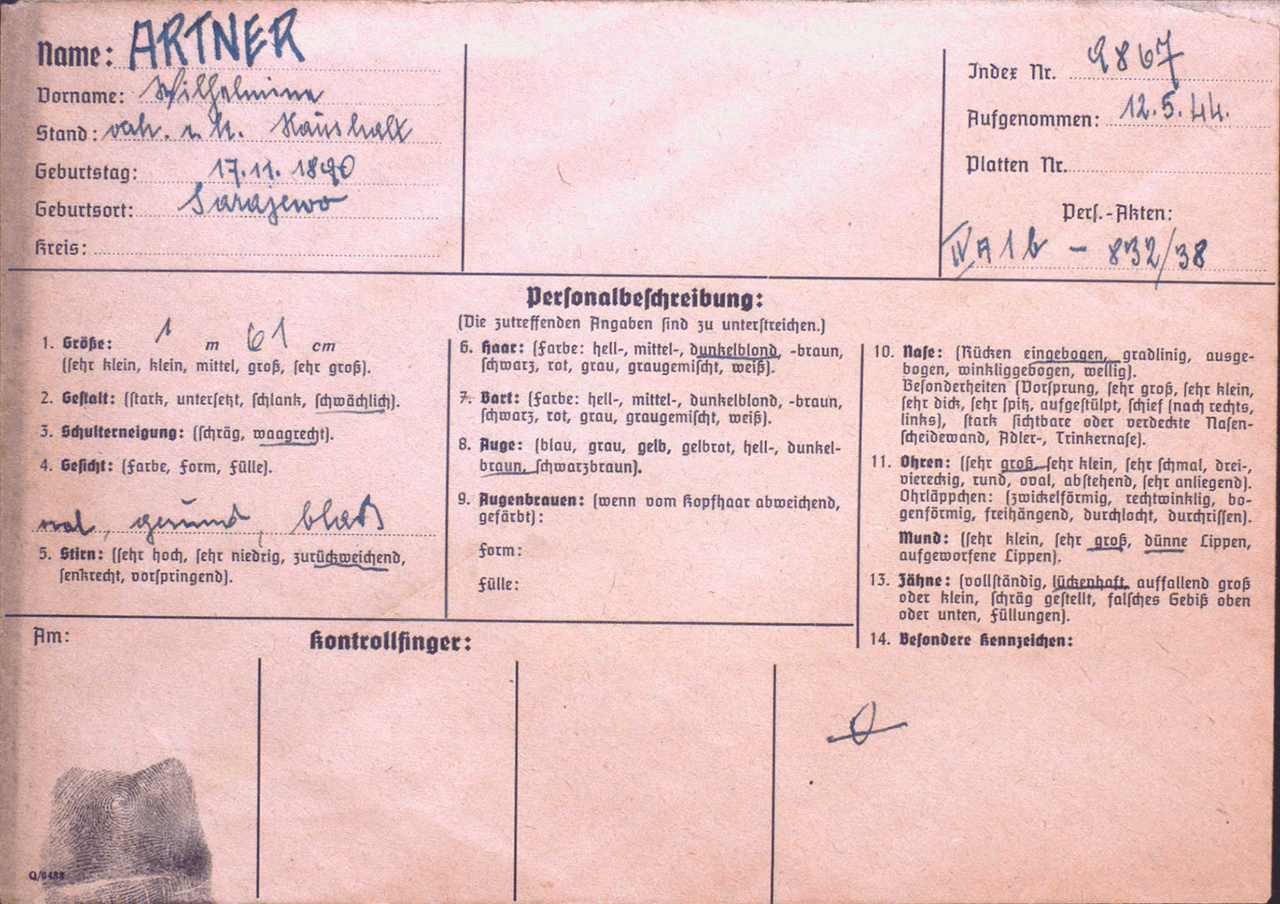

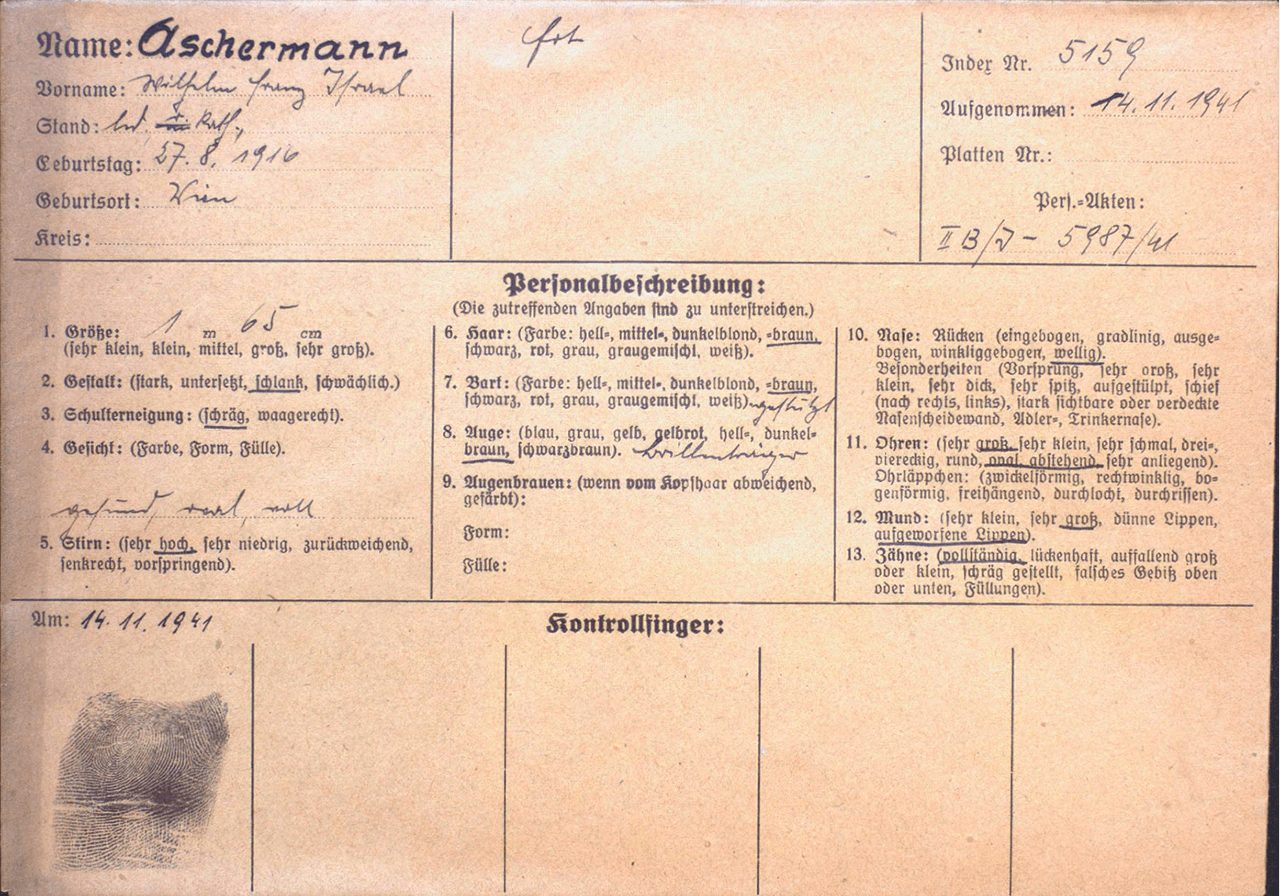

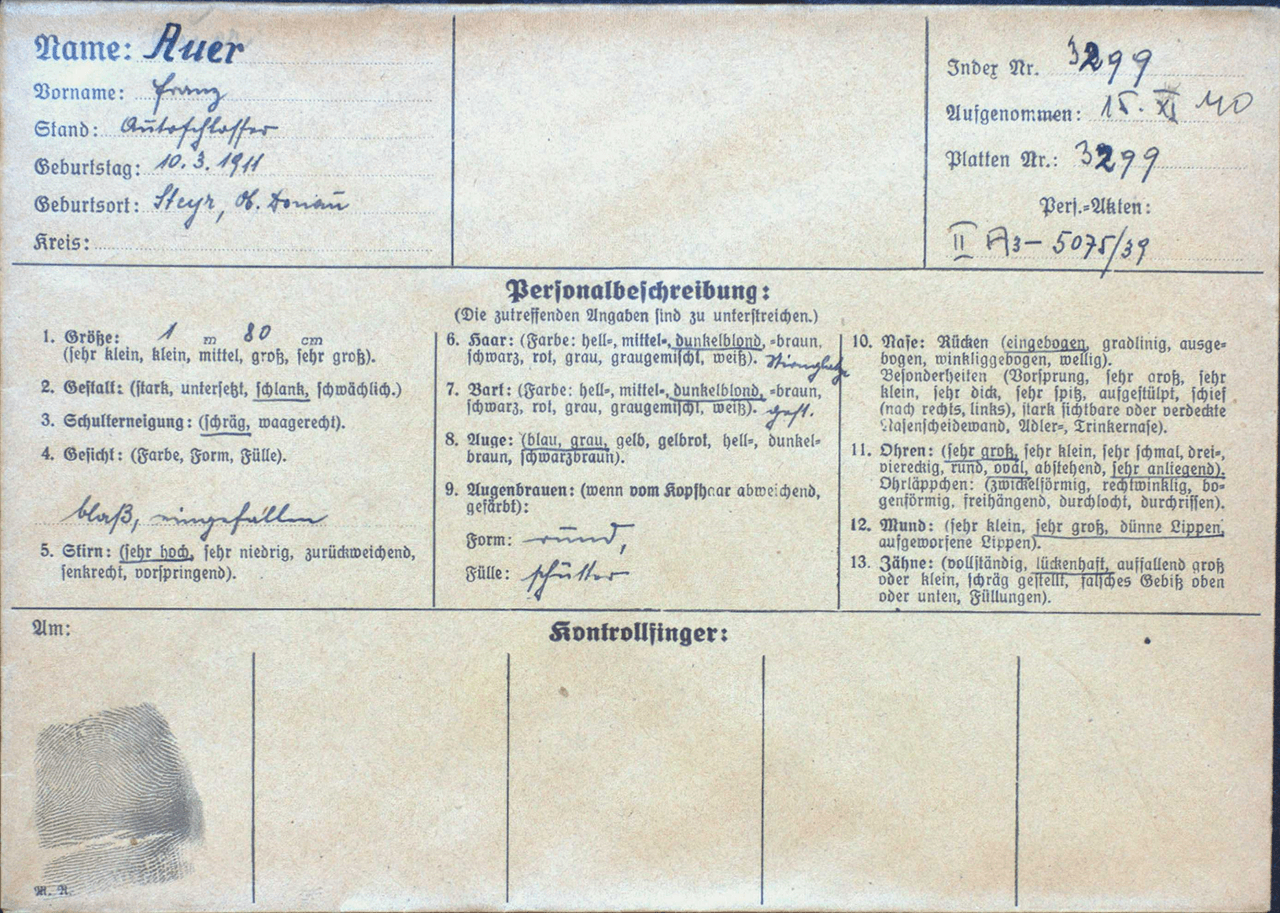

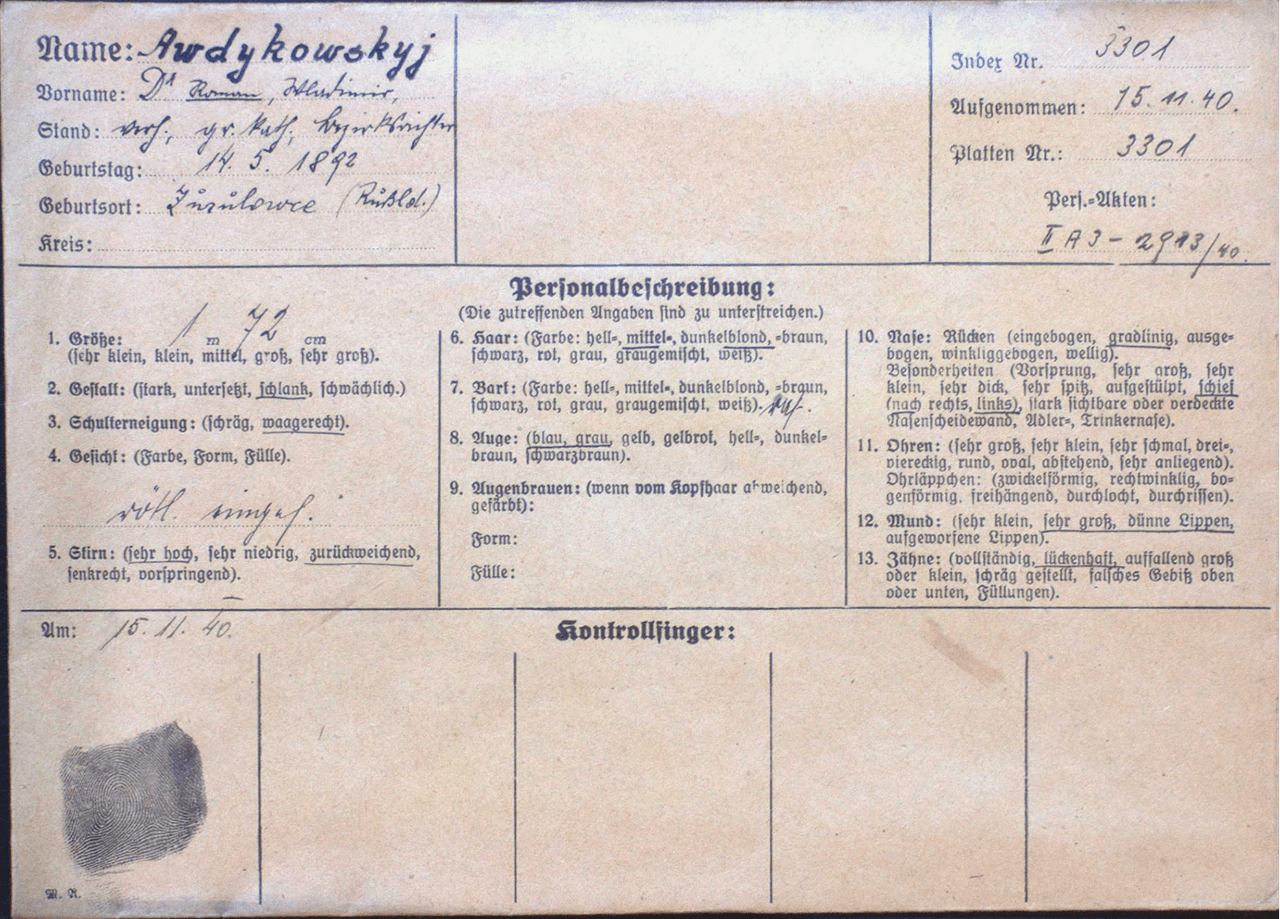

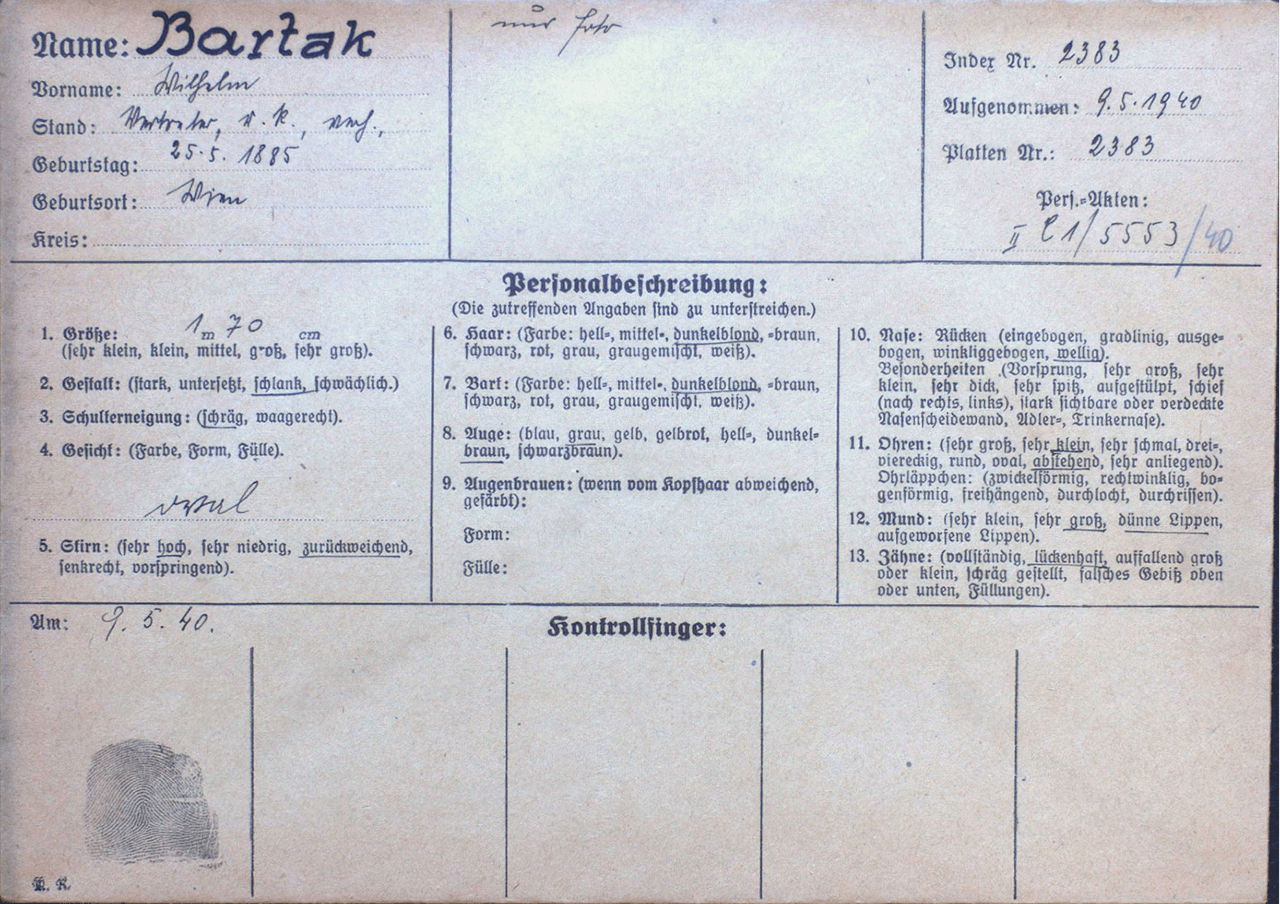

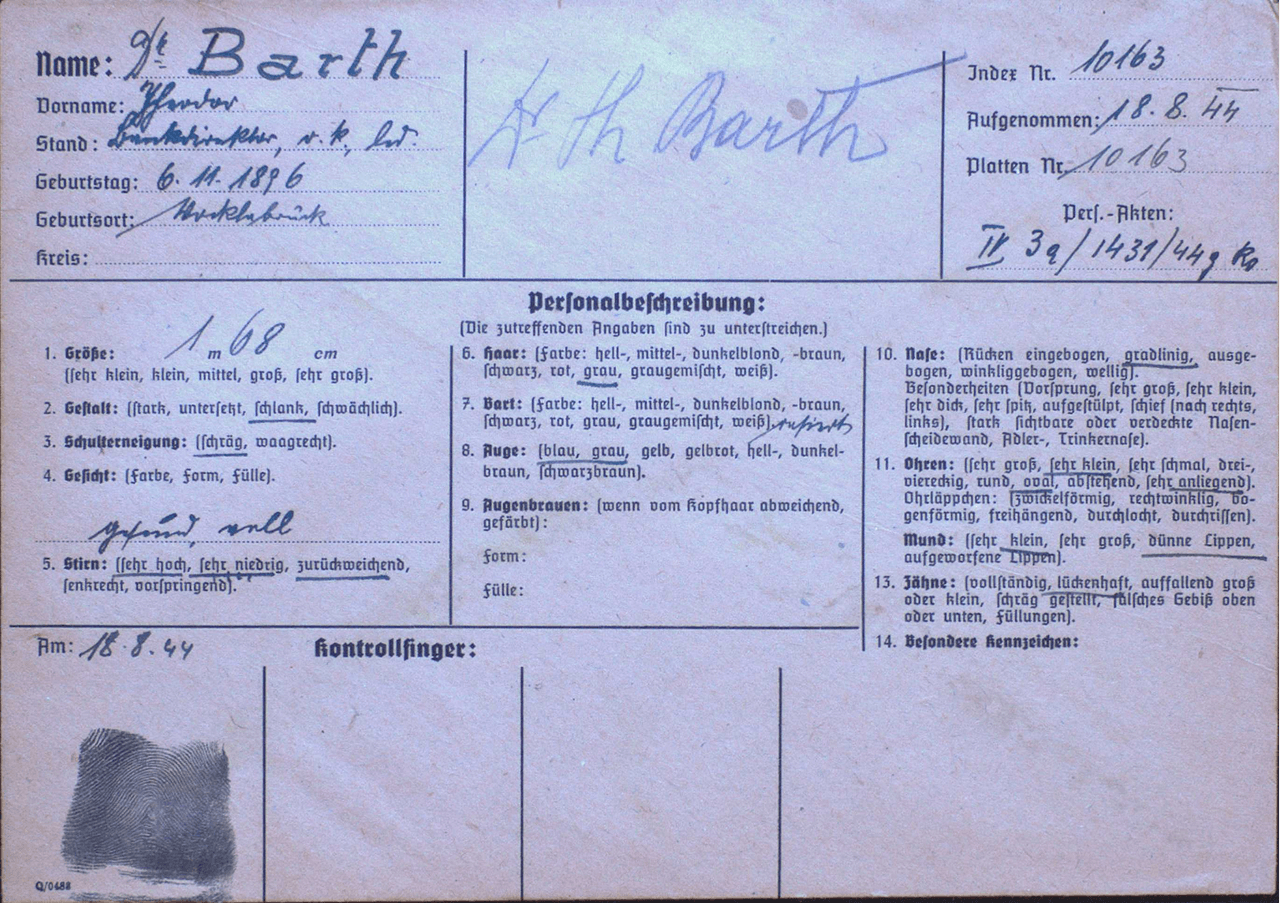

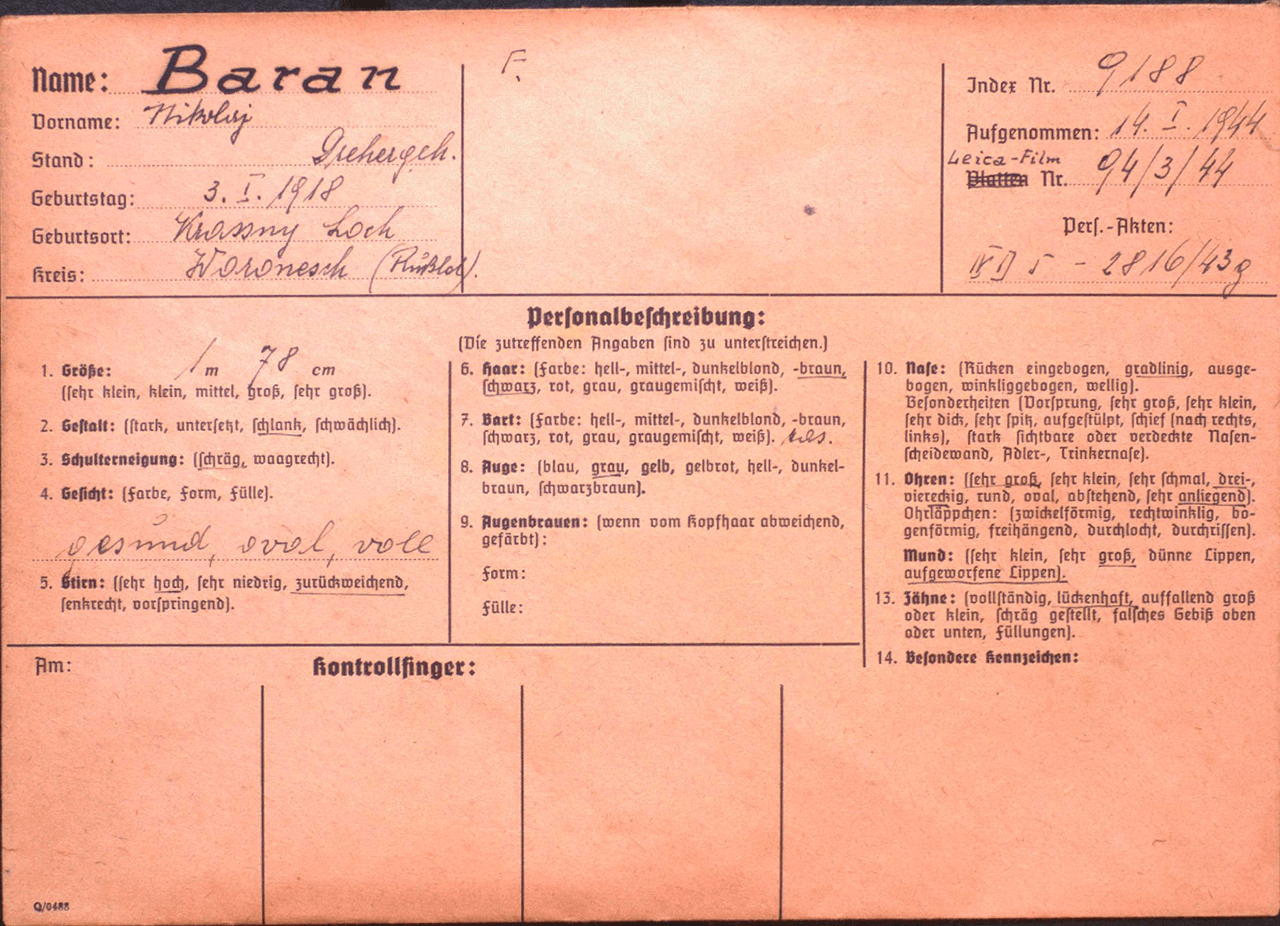

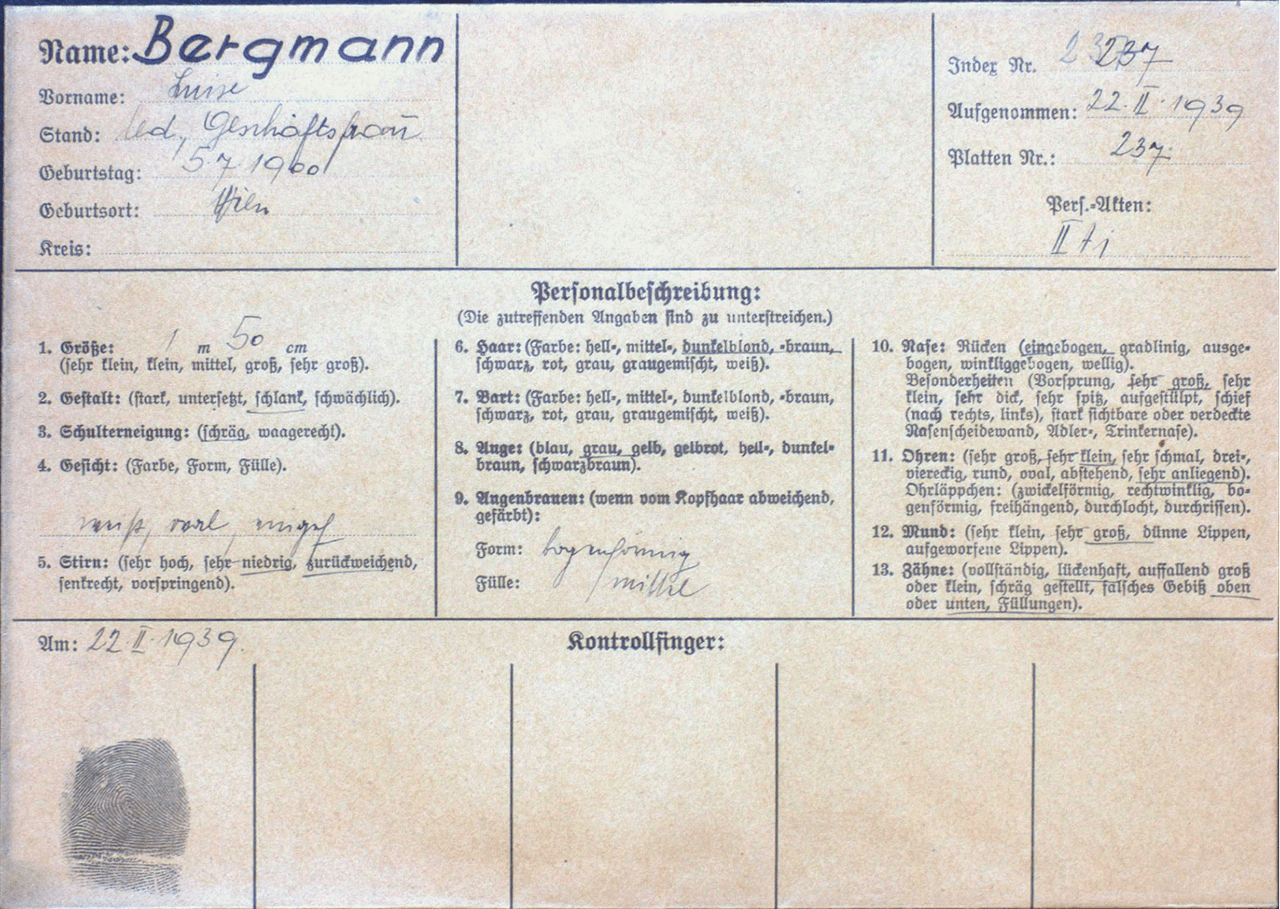

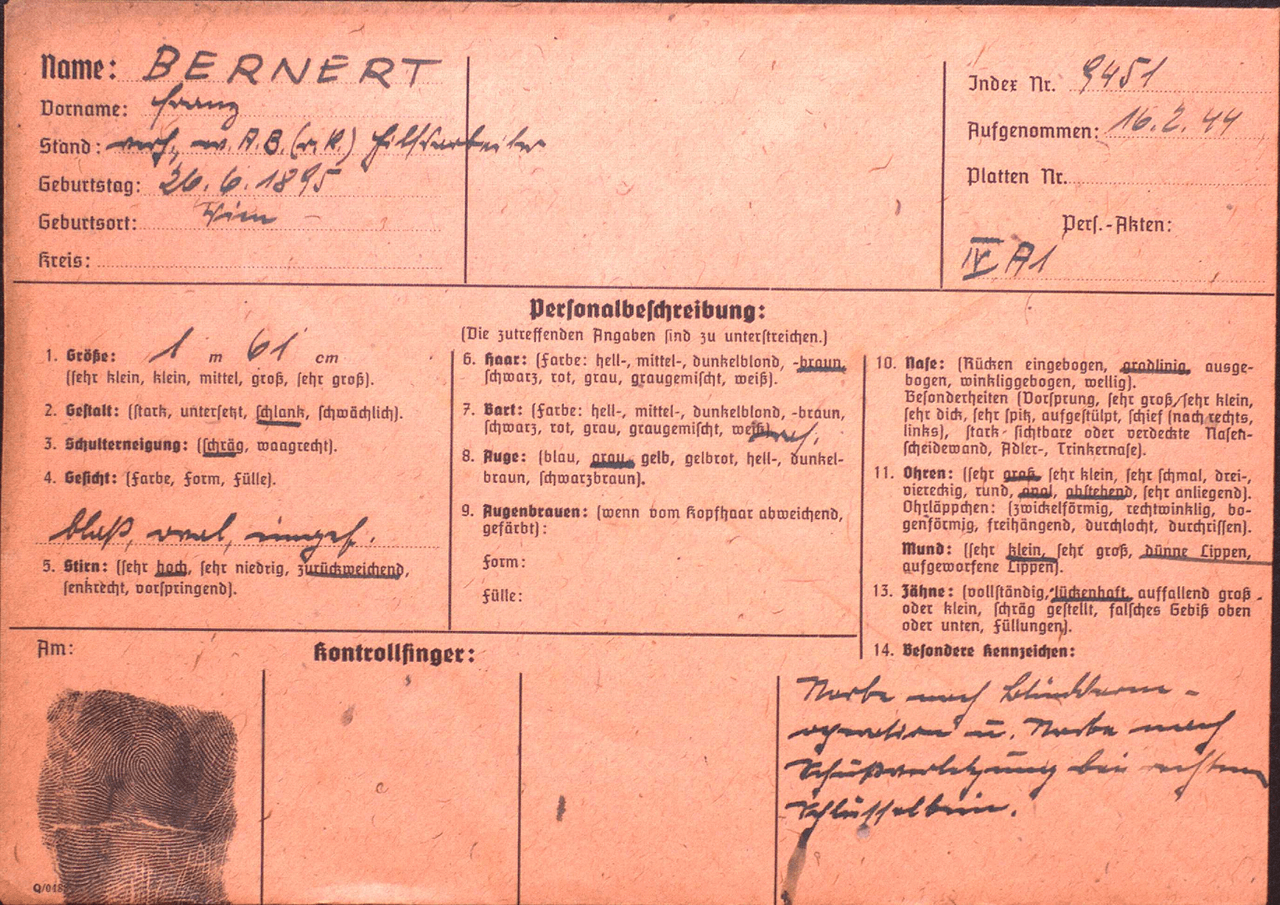

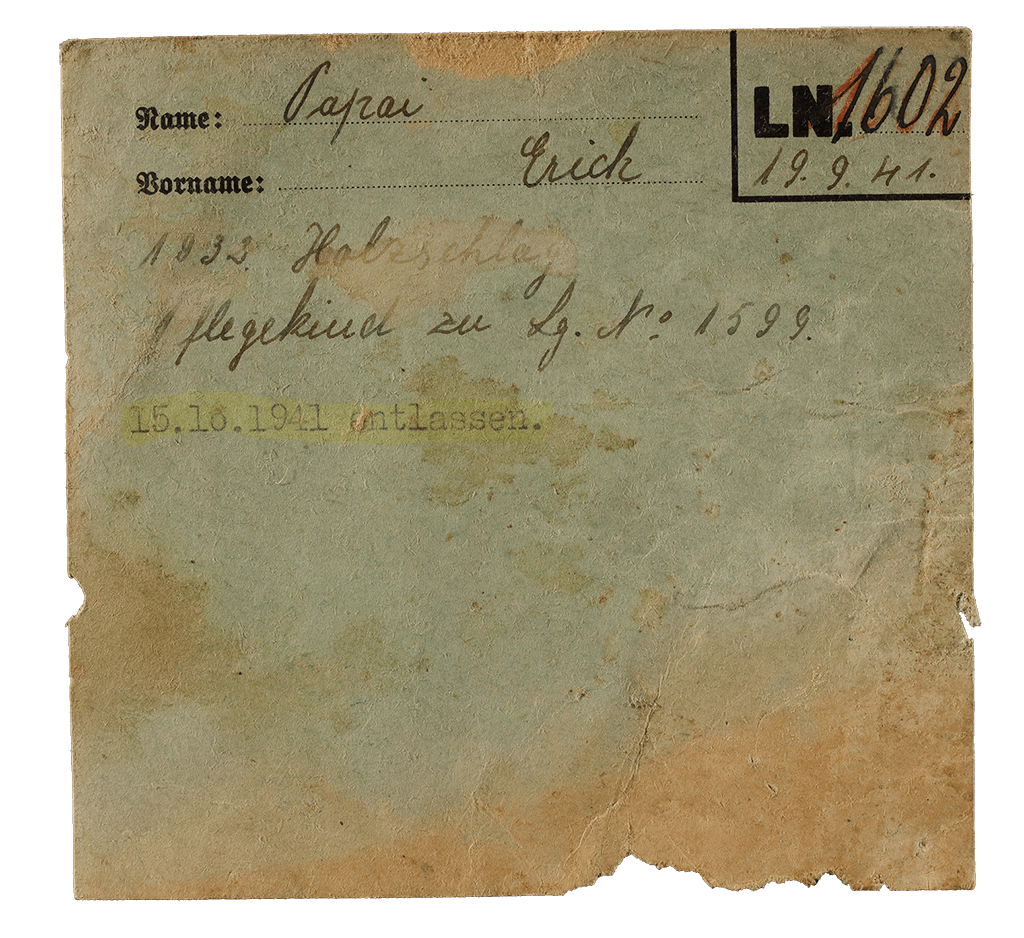

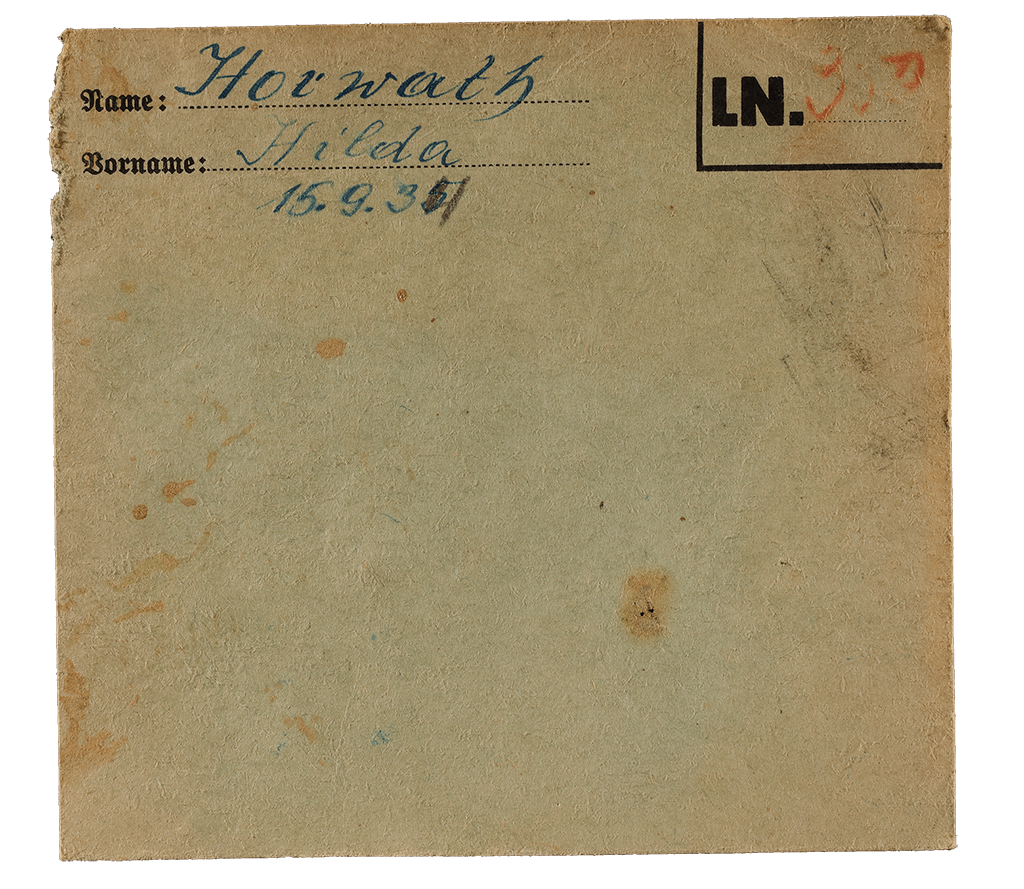

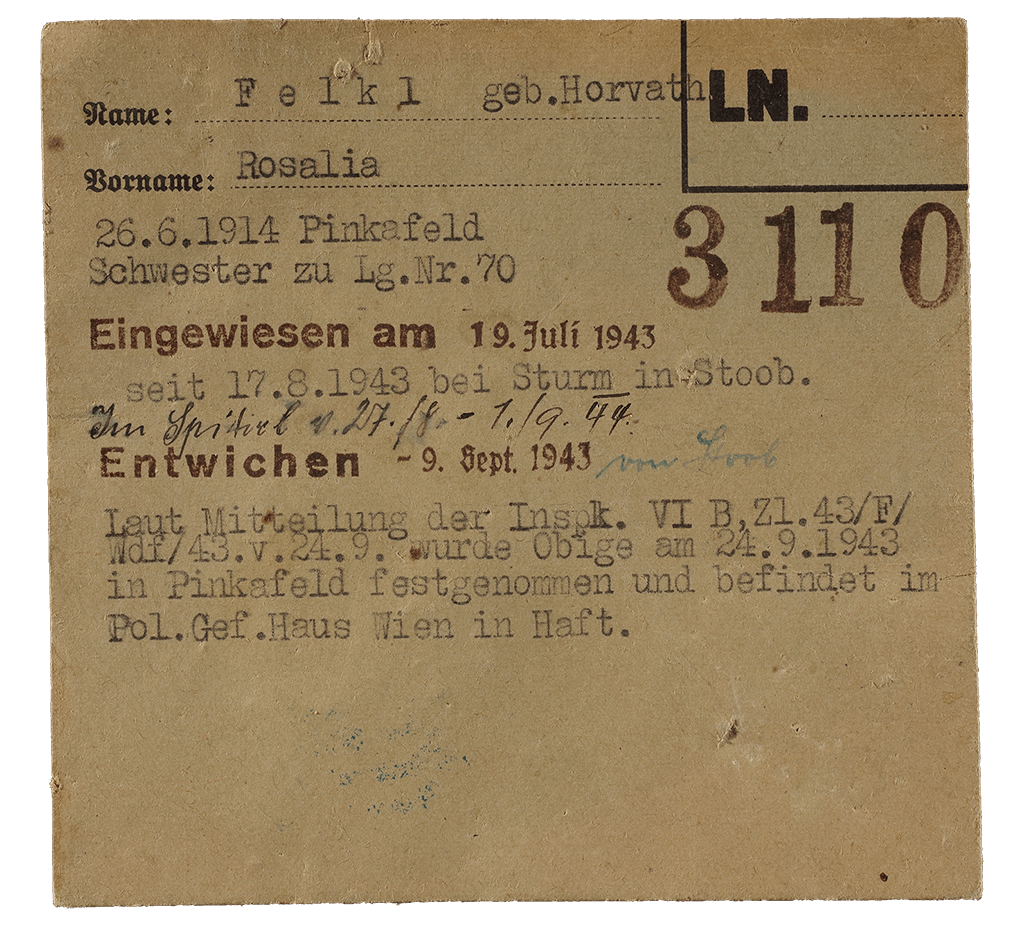

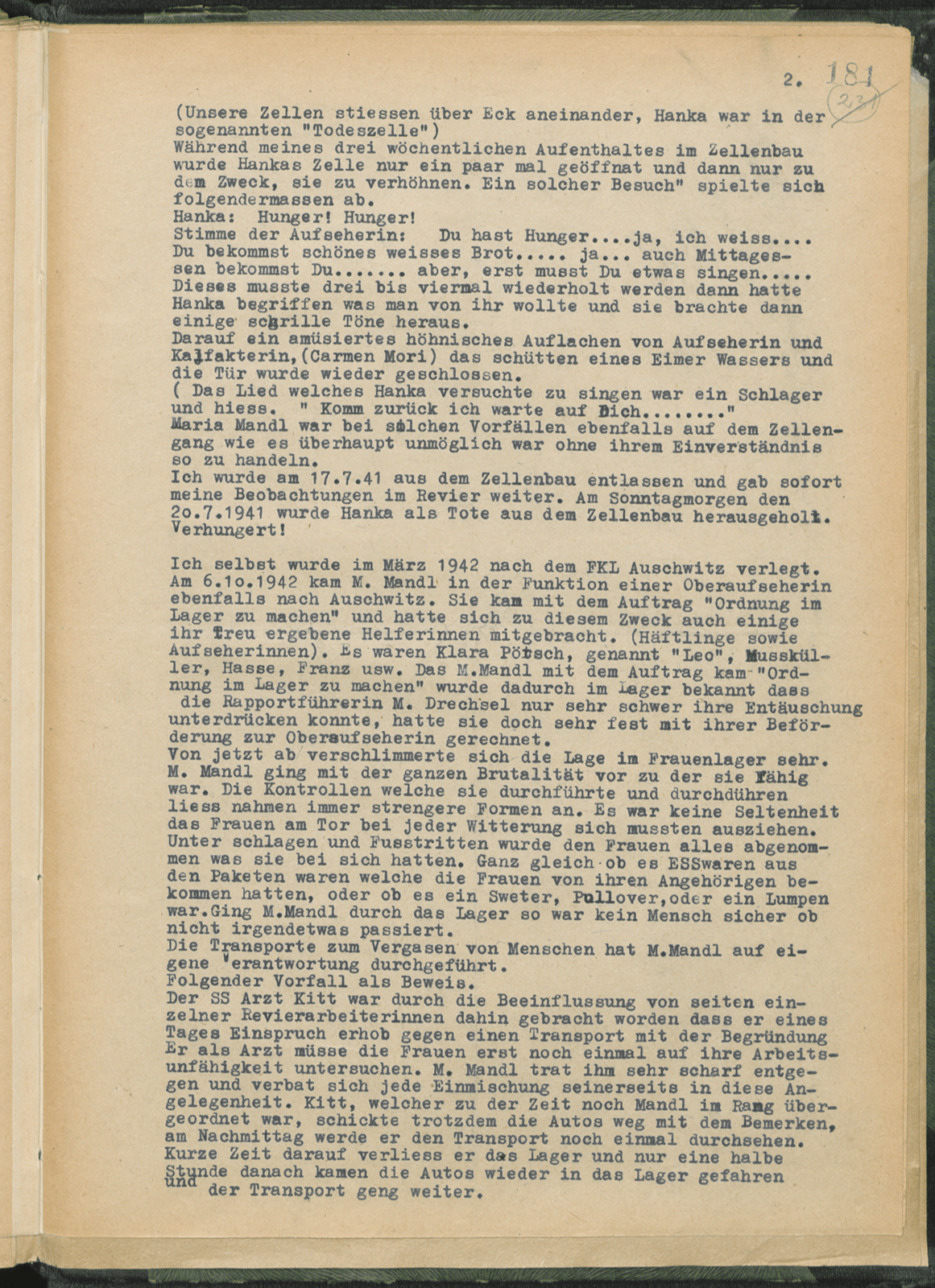

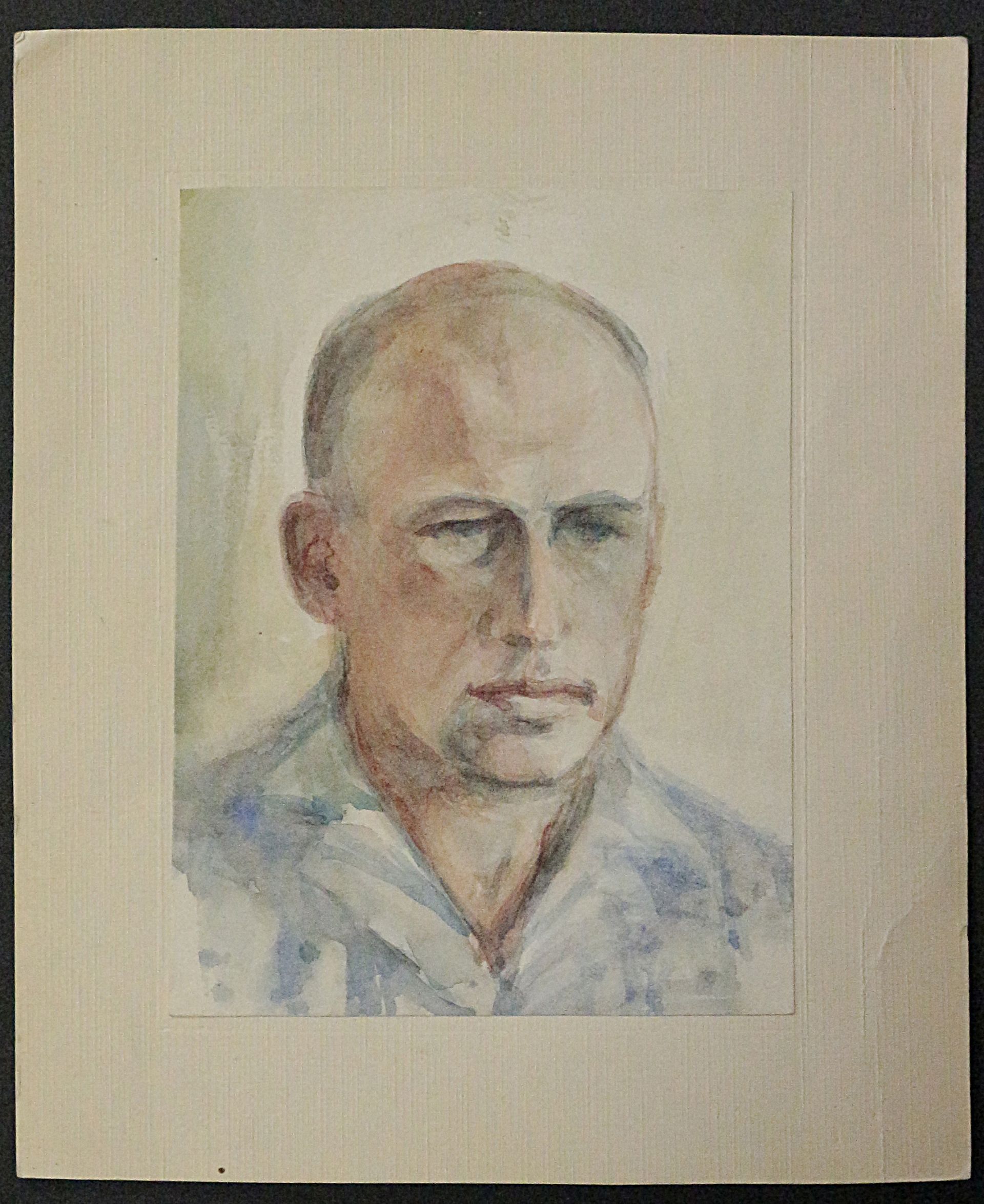

Hermann Langbein was a political prisoner in the “main camp” Auschwitz I. He was a stenographer for the SS doctor Eduard Wirth and a member of the international camp resistance movement. After 1945 he systematically gathered testimonies from former inmates and collected information on the camp’s staff. These index cards formed the basis for his decades spent working to document the atrocities committed at Auschwitz. His work made a valuable contribution towards bringing Nazi criminals to justice.

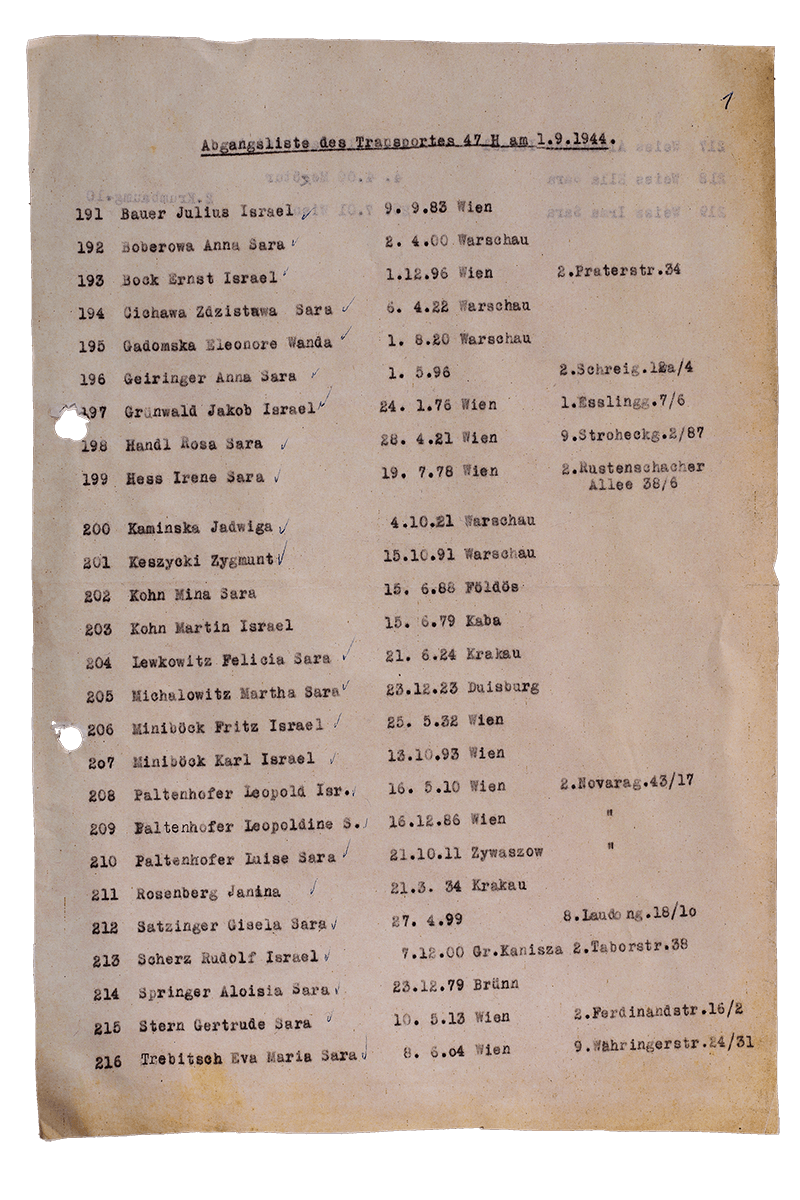

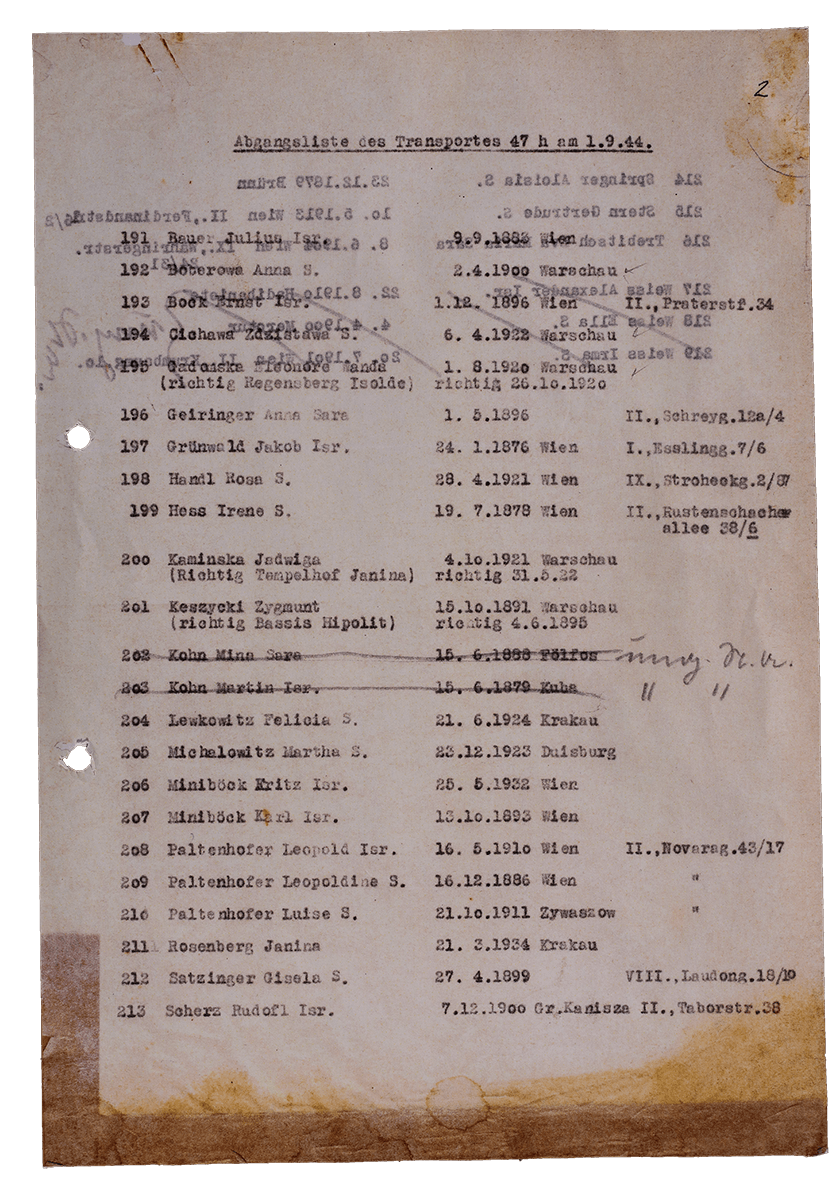

From 1939 to 1942 the majority of trains used to deport Jews from Austria to the concentration camps departed from Aspang Railway Station. Later on, the “transports” mainly left from Vienna’s Northern Railway Station, like those carrying Roma and Sinti. People were also deported to the death camps from other railway stations throughout Austria.

After World War I, polarisation among social groupings and political factions began to grow in Austria, like in many European countries. Democracy and parliamentarianism became increasingly unpopular. Violent clashes between the various political factions shaped the political climate. This made way for the rise of the Austrian Nazi Party, which became a mass movement in the early 1930s and pursued its goals with brute force.

Despite being outlawed in June 1933, it continued to spread terror and propaganda, culminating – under massive political, economic and military pressure from Germany – in the “Anschluss” to the German Reich on 13 March 1938, which was greeted with euphoria by many Austrians. The invasion of the German Wehrmacht in March 1938 marked the onset of Nazi rule in Austria.

Nazi tyranny was swiftly established in Austria. The Nazi regime legalised violence and oppression and incited hatred against its enemies. Brutal attacks on Jews and political opponents had already taken place during the days surrounding the “Anschluss”. In contrast, broad sections of the Austrian population profited from the new system and welcomed the persecution measures it entailed. New career opportunities opened up for them. The anti-Jewish measures reached a climax marked by the organised pogrom on 9/10 November 1938, in which virtually every Austrian synagogue and prayer house was destroyed, innumerable shops were looted and people abused and murdered. In Vienna alone, almost 5,000 Jewish men were arrested and deported to concentration camps.

The end of World War I also marked the end of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. The breakup of the vast economic region and the underdevelopment of the agricultural sector resulted in repeated famines, which led to rioting and unrest. Inflation and unemployment reached devastating proportions.

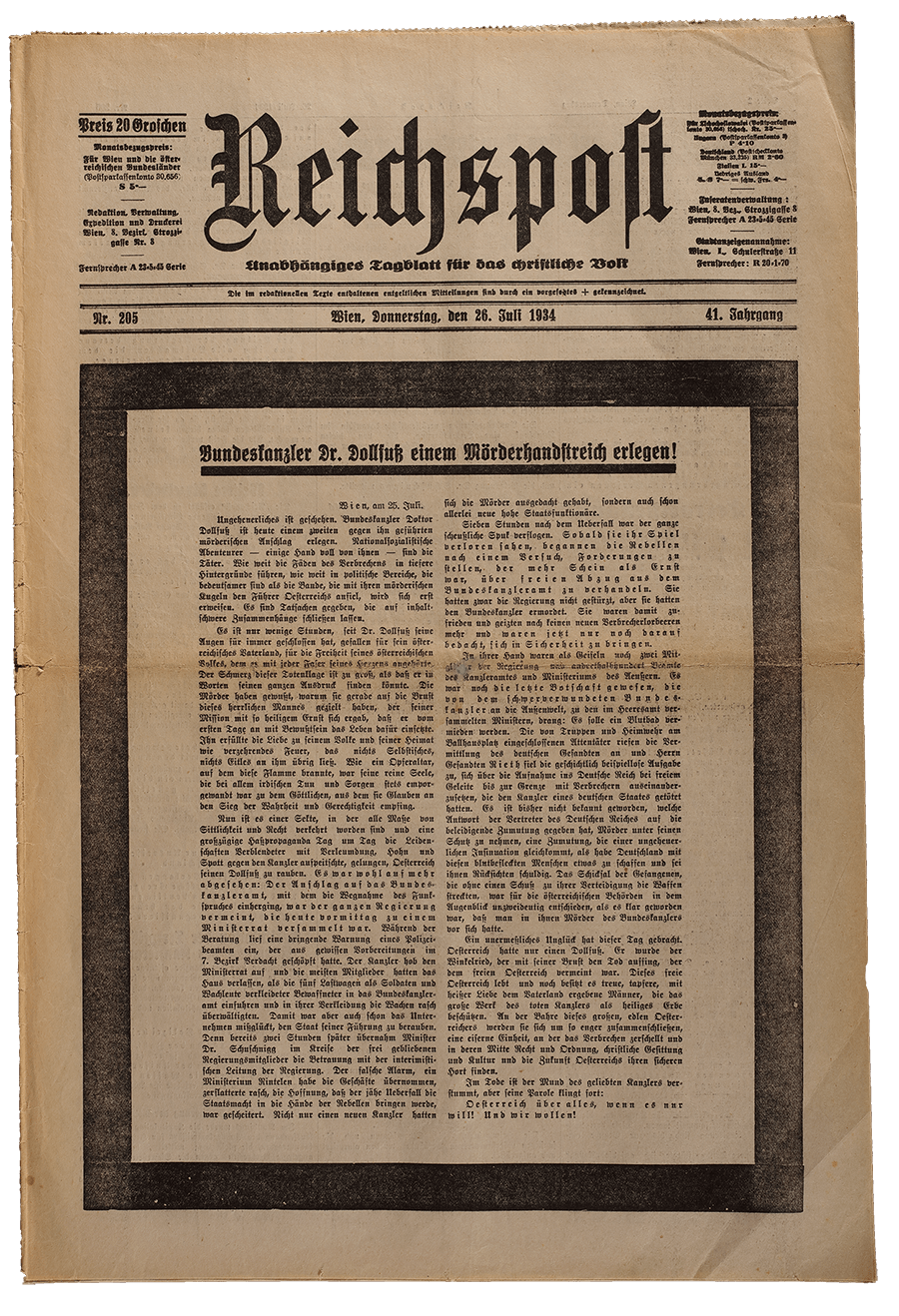

From 1927, violent clashes between political groups escalated into a latent civil war. In parallel to developments in Germany, the early 1930s also saw the rise of the Nazi Party in Austria, where it recorded enormous gains in the provincial parliament and municipal council elections in the spring of 1932. This led to a fragmentation of the bourgeois bloc and a marked shift to the right. Consequently, there were calls for an authoritarian state and the abolition of the party state and democracy. At the same time, from autumn 1932 onwards, the government under Engelbert Dollfuß began to circumvent the National Council by using the “War Economy Enabling Act” to achieve its goals, until 4 March 1933 when it took advantage of a voting error to gradually abolish the democratic system. From then on it ruled by means of illegal emergency decrees and established a dictatorship modelled on Italian fascism (“Austrofascism”). In May 1933, the Austrian Communist Party was banned from all and any activities. Following violent clashes in February 1934 between the Social Democrats and the Austrofascist government, the Social Democratic Party was banned.

The bombings carried out by the Vienna SS in June 1933 set the course for the terrorist activities of the Austrian Nazi Party. Despite being outlawed on 19 June 1933, the Nazi Party continued to carry out acts of terrorism illegally, with support from Germany. This development culminated in the attempted coup of July 1934, during which Chancellor Dollfuß was assassinated by members of the Vienna SS.

Austria's relations with Nazi Germany became increasingly strained as the German Reich exerted massive political, economic and military pressure. This finally culminated in the "Anschluss" of 13 March 1938, which was greeted with euphoria by many Austrians. Upon the invasion of the German Wehrmacht in March 1938 Nazi rule commenced in Austria.

The establishment of Nazi tyranny in Austria was marked by brutal attacks on the Jewish population and the arrest of thousands of political opponents. Broad sections of the Austrian population profited from the new system, many partook in the looting and violence. The hostile measures against Jews reached a climax with the organised pogrom of 9/10 November 1938, during which virtually every Austrian synagogue and prayer house was destroyed, innumerable shops were looted and in Vienna alone almost 5,000 Jewish men were arrested and deported to concentration camps.

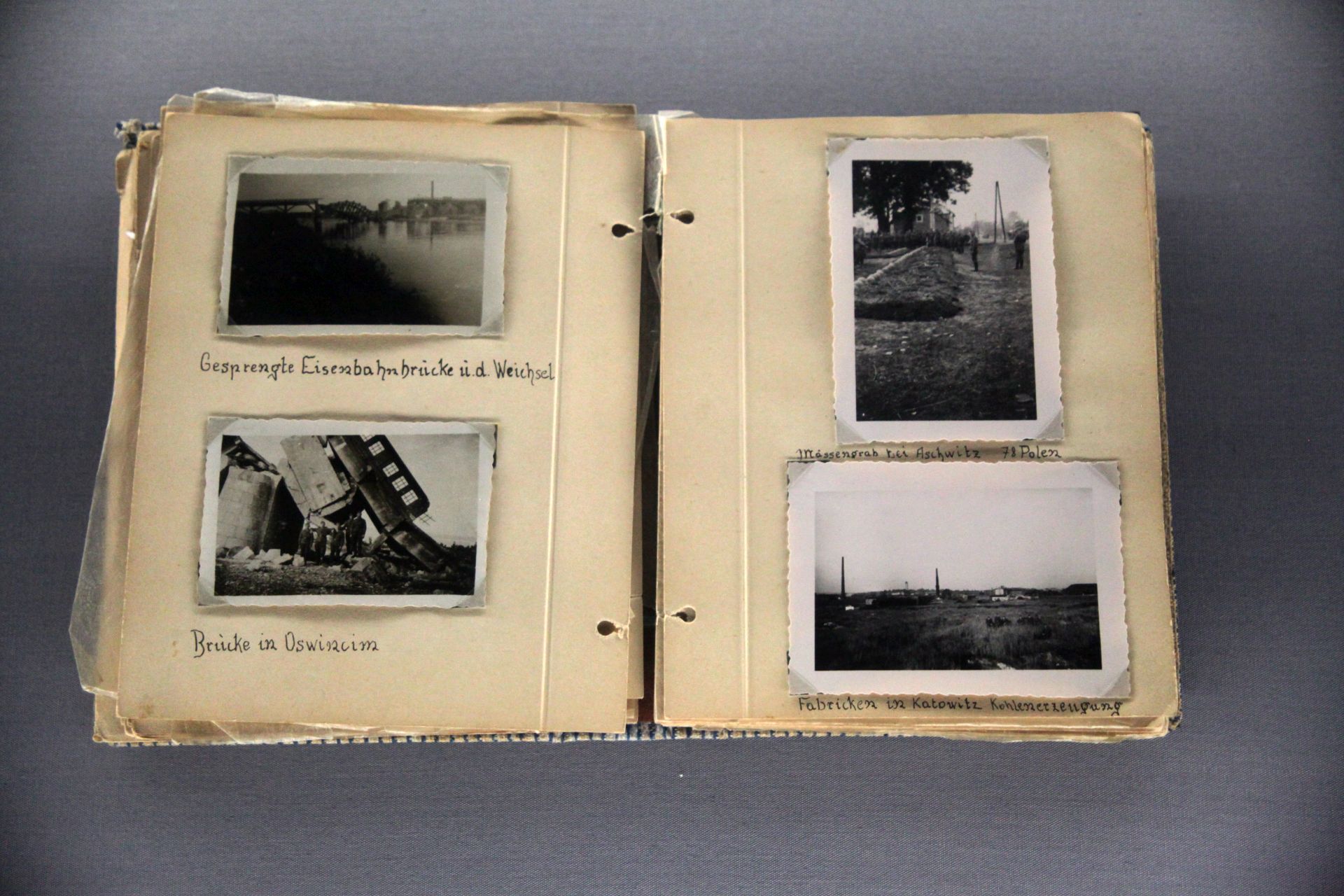

From 1772 to 1918, the Duchy of Auschwitz belonged to the Habsburg Monarchy, until becoming part of Poland after the end of World War I. Following the invasion of the German Wehrmacht, in September 1939 fierce fighting also broke out in the town of Auschwitz, in Polish Oświęcim. Auschwitz became part of the German Reich. The racist Lebensraum (“living space”) policy foresaw the resettlement of the resident Jewish and non-Jewish Polish population from there as well in order to make space for Germans.

On 1 February 1940, Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler launched a search to find a suitable site for another concentration camp. The choice fell on the site of the former Austro-Hungarian barracks in Auschwitz, as it had a suitable railway connection.

At first, Auschwitz was mainly used as a concentration camp for Polish prisoners; they were later joined by Soviet POWs and then by other persecuted groups, particularly Jews and Roma and Sinti. From 1942 onwards, Auschwitz became the largest extermination camp for Europe’s Jewish population.

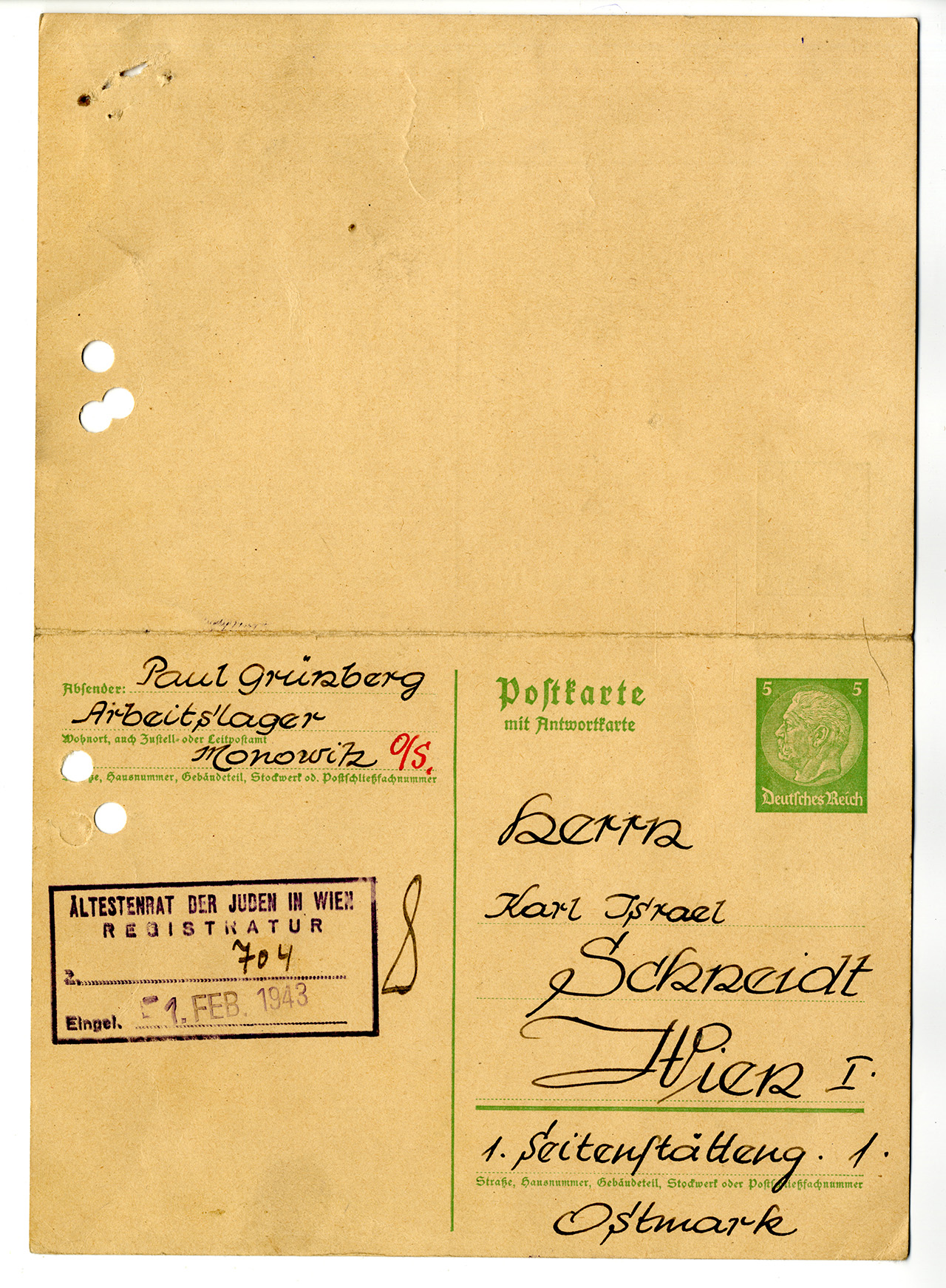

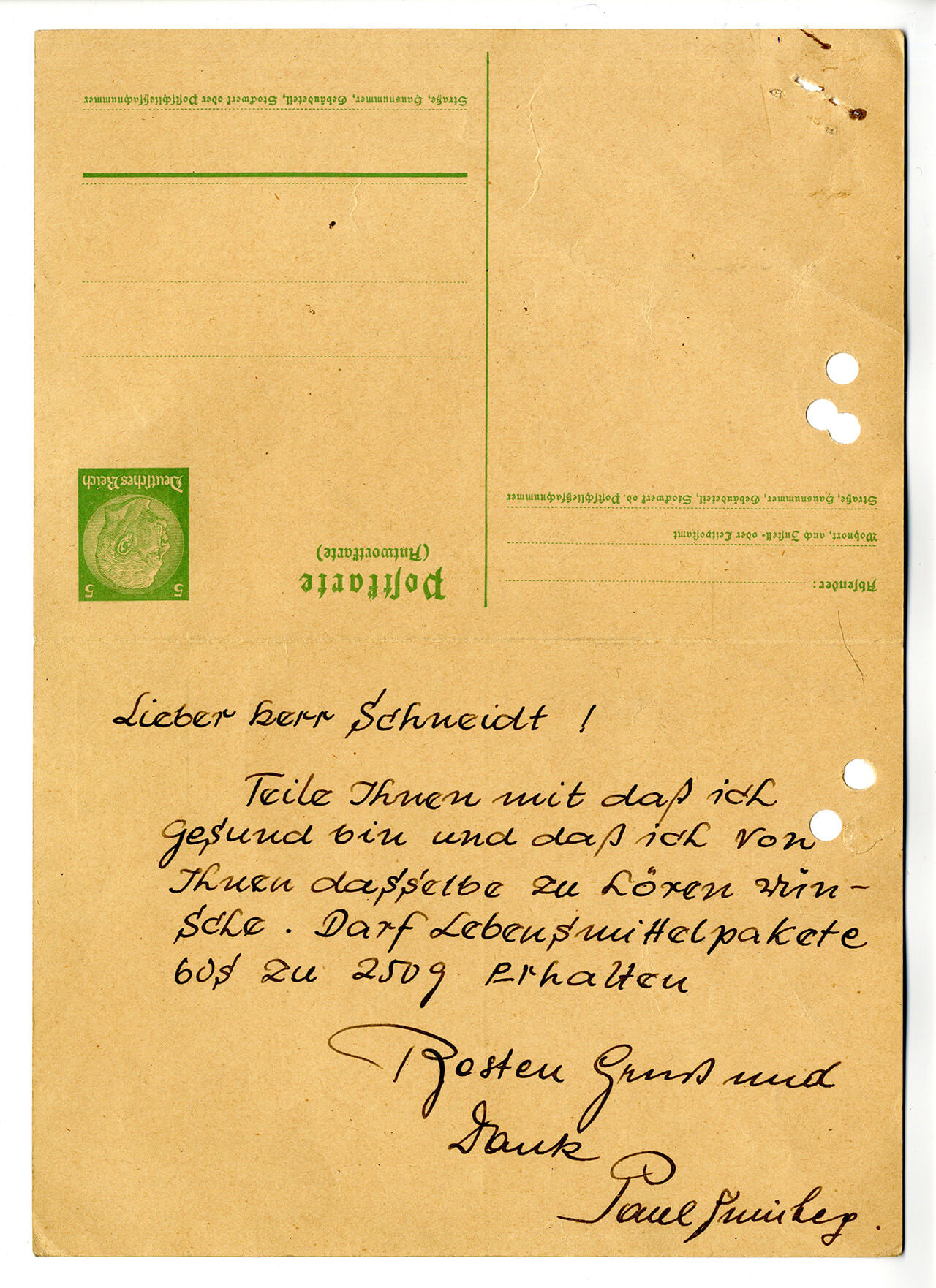

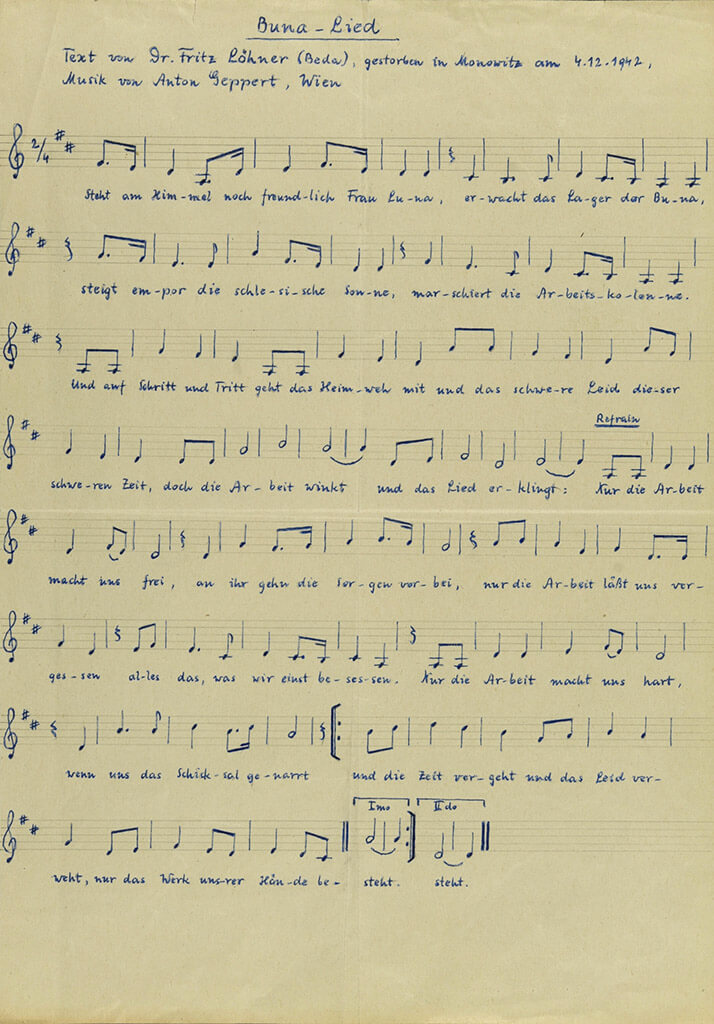

On 27 April 1940, Heinrich Himmler ordered the construction of a concentration camp in Auschwitz. The first transports carrying prisoners arrived there in late May 1940. Those prisoners and the Polish civilian population were forced to build what was later known as the main camp Auschwitz I. At that time, Auschwitz was primarily a concentration camp for Polish prisoners. In February 1941, it was expanded to include the subcamp Monowitz, where inmates were deployed as slave labourers for the German company IG-Farben. Following the invasion of the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941, planning commenced for the concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau (Auschwitz II) in the village of Brzezinka, approximately three kilometres from the main camp Auschwitz I. Initially intended as a camp for Soviet POWs, it soon became one of the central sites used for the extermination of European Jewry.

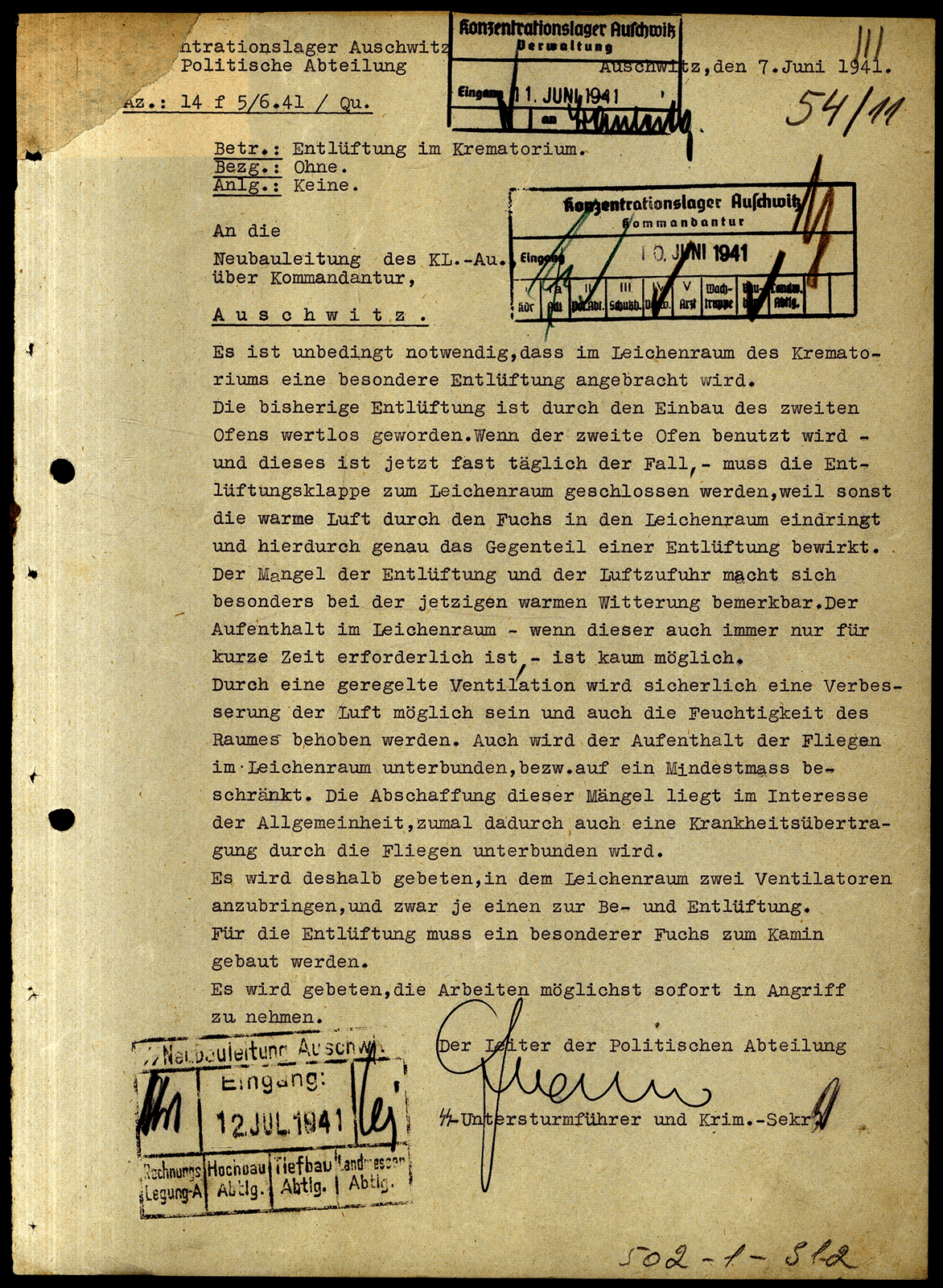

Poisonous gas had been used to murder prisoners at Auschwitz from autumn 1940 onwards, initially in the main camp and, later on, also in two former farmhouses in Birkenau. In December 1941, the decision was made to integrate large gas chambers into the crematoria facilities, turning the concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau into an extermination camp.

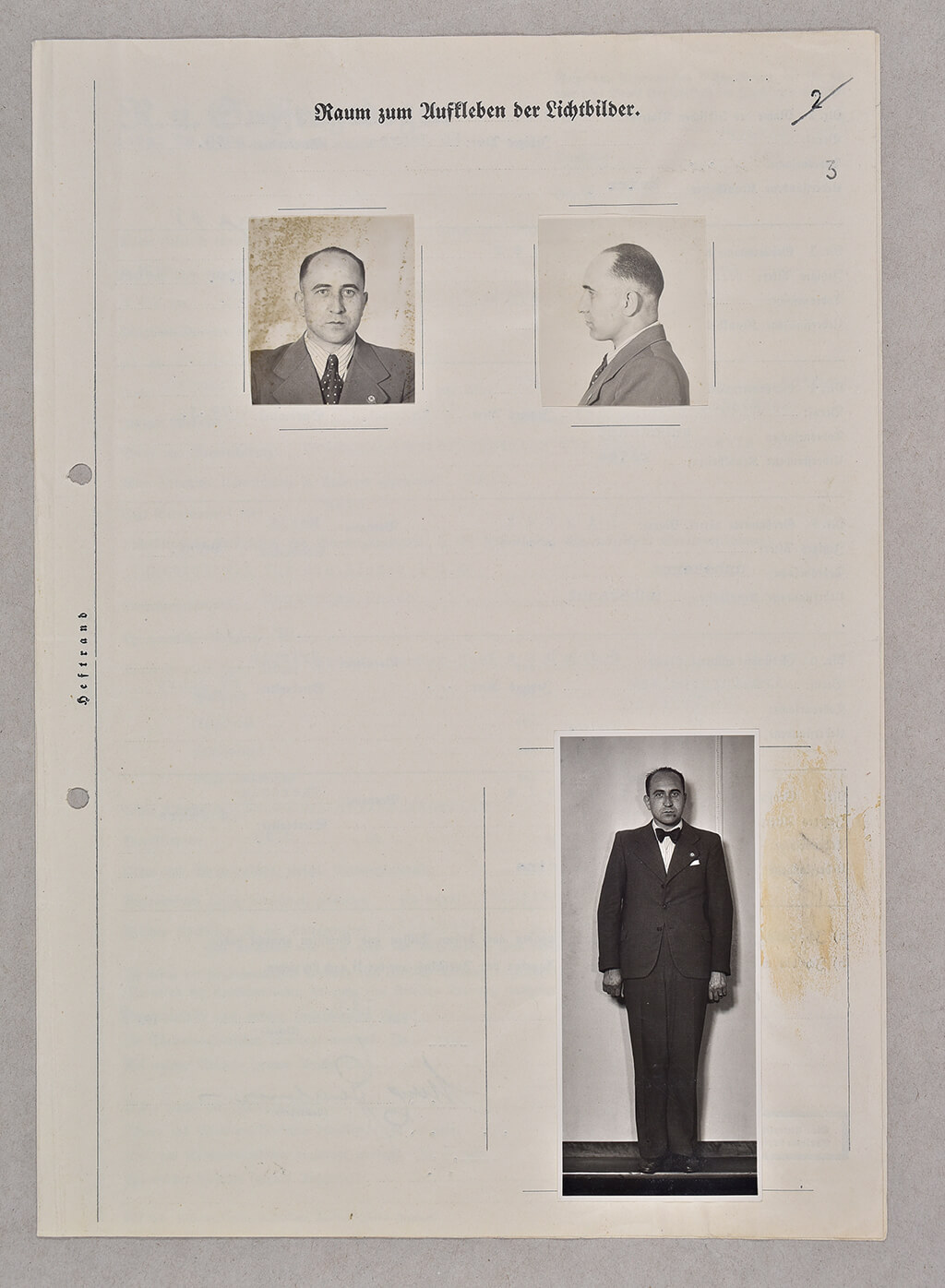

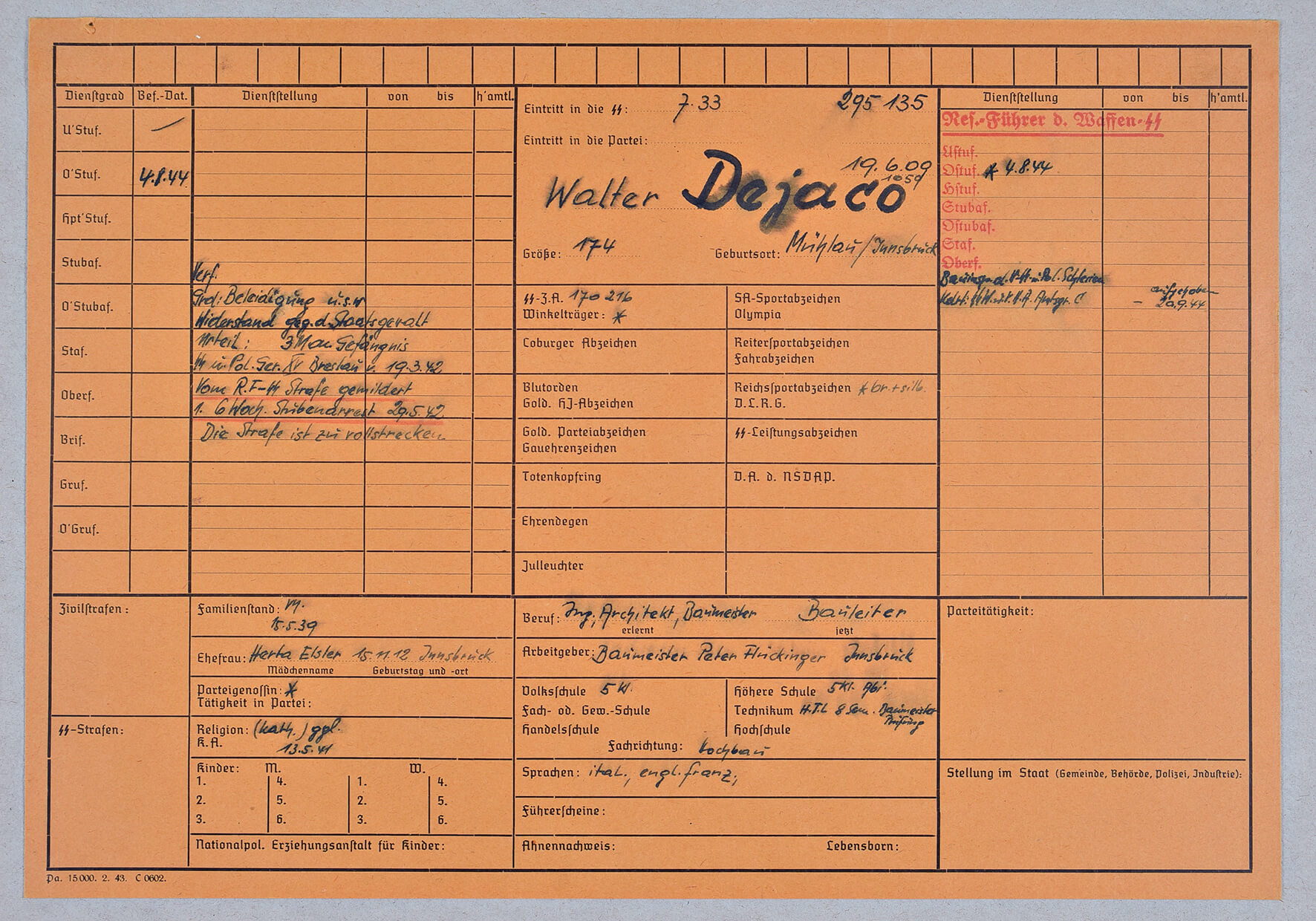

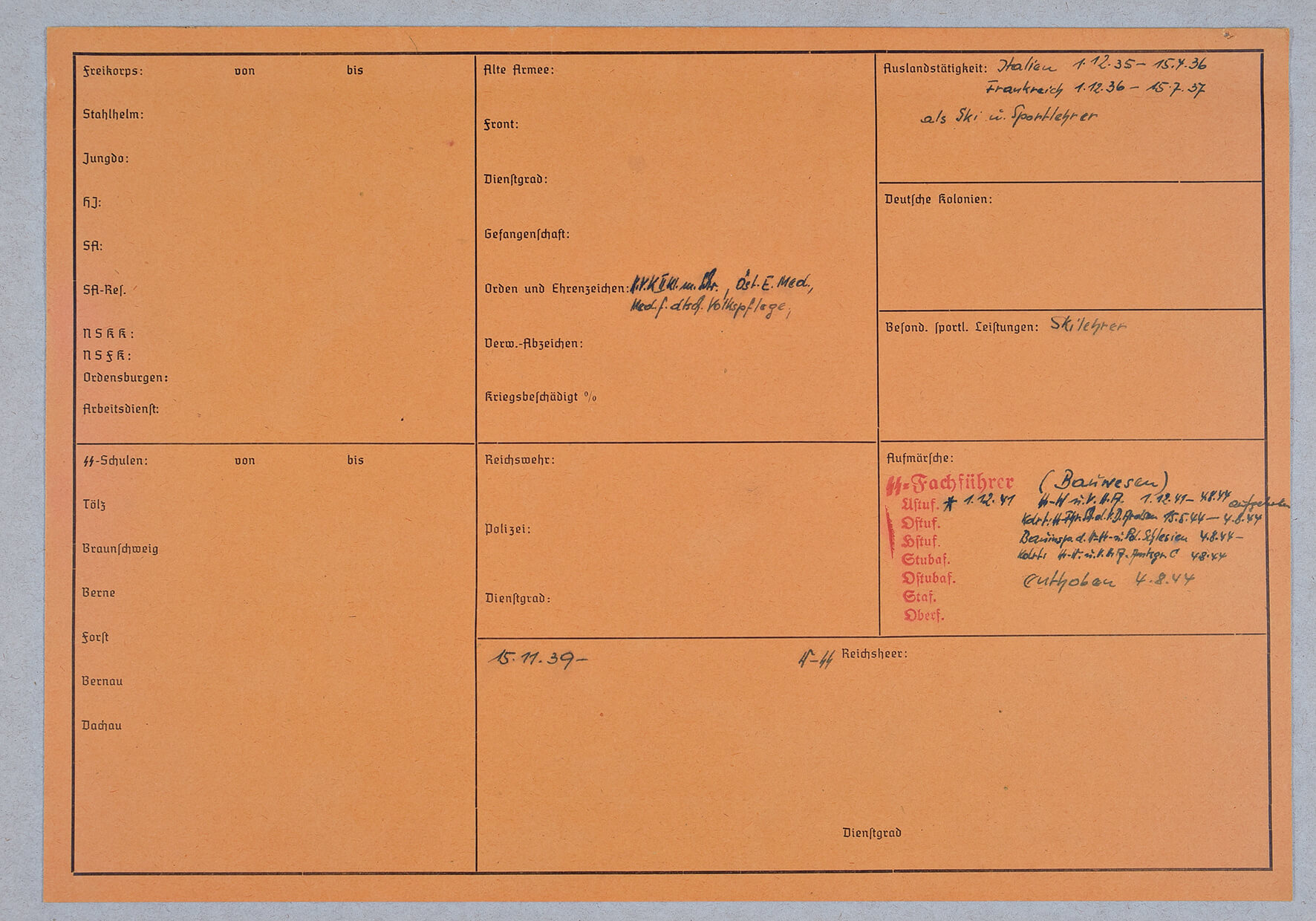

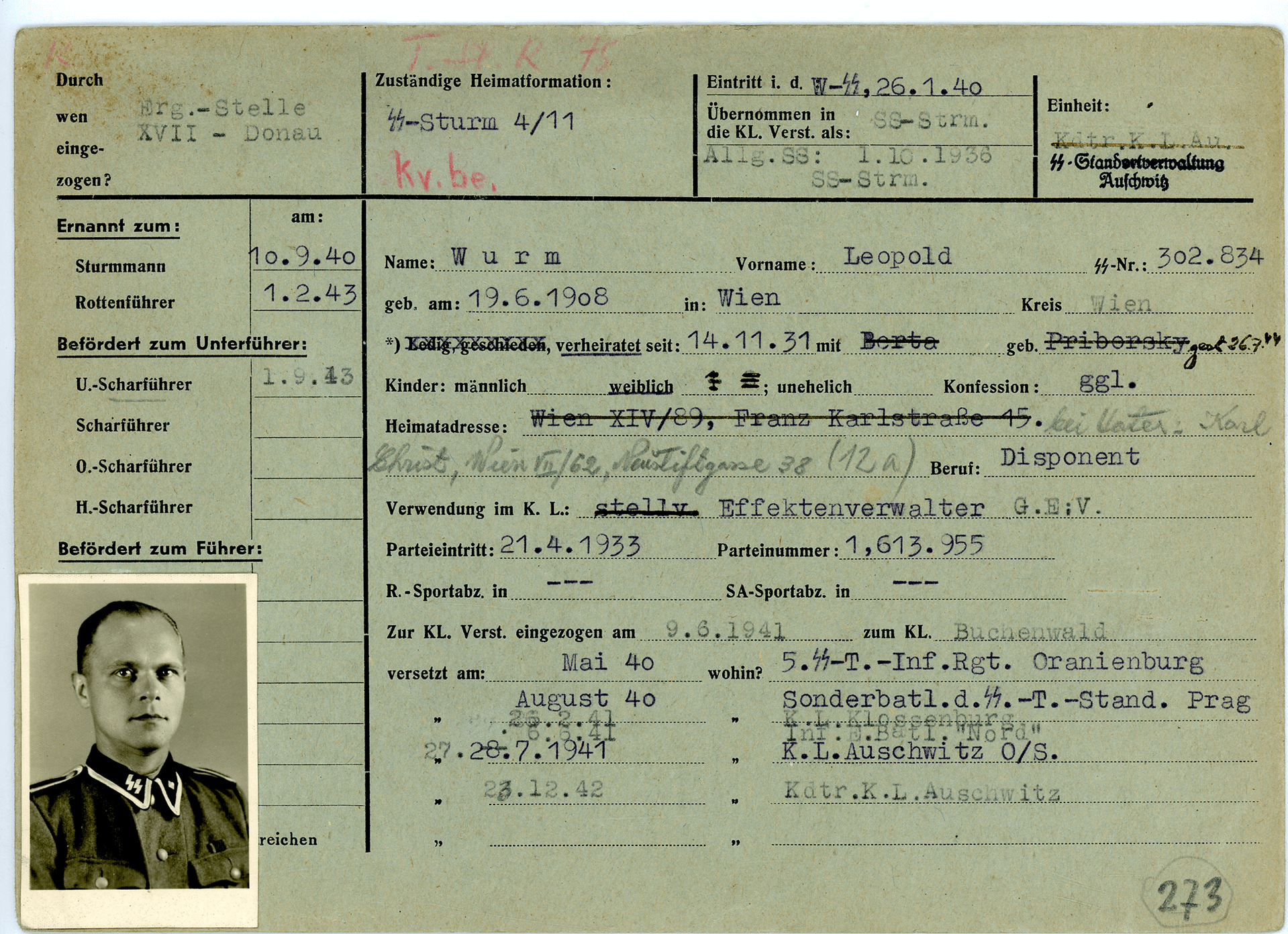

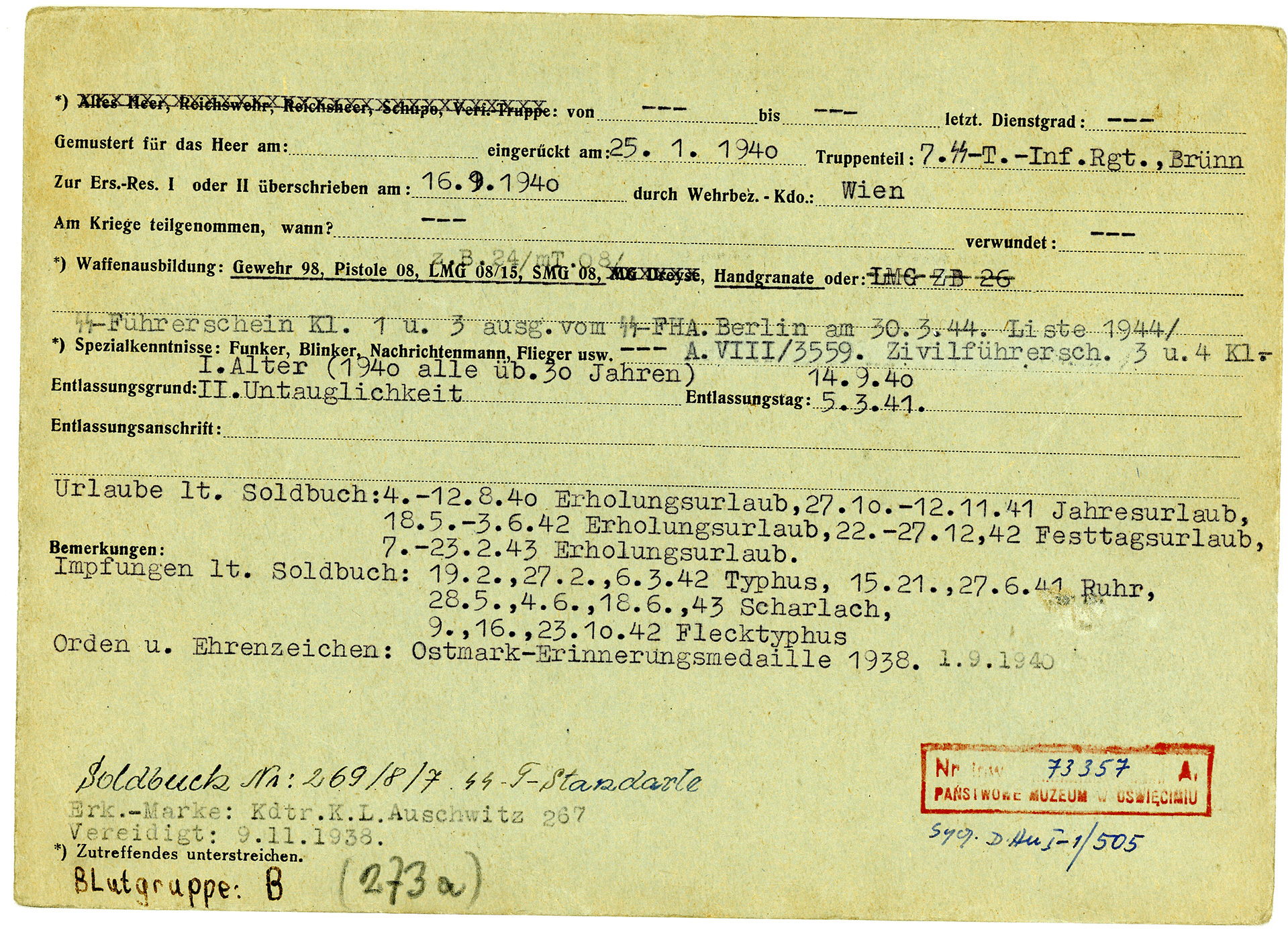

The SS Central Construction Office played a key role in the construction of the camp complex. It was in charge of the planning and execution of the construction work. A number of Austrians played pivotal roles there from the very start, particularly the architects Walter Dejaco from Tyrol and Fritz Ertl from Upper Austria. The construction of the extermination facilities was overseen by Josef Janisch from Salzburg, who was feared for his brutality.

The Auschwitz camp complex was, as such, a hybrid of concentration camp, POW camp, slave labour camp and extermination camp. In addition to the three central sections of the camp, prisoners also had to perform slave labour in about 50 subcamps.

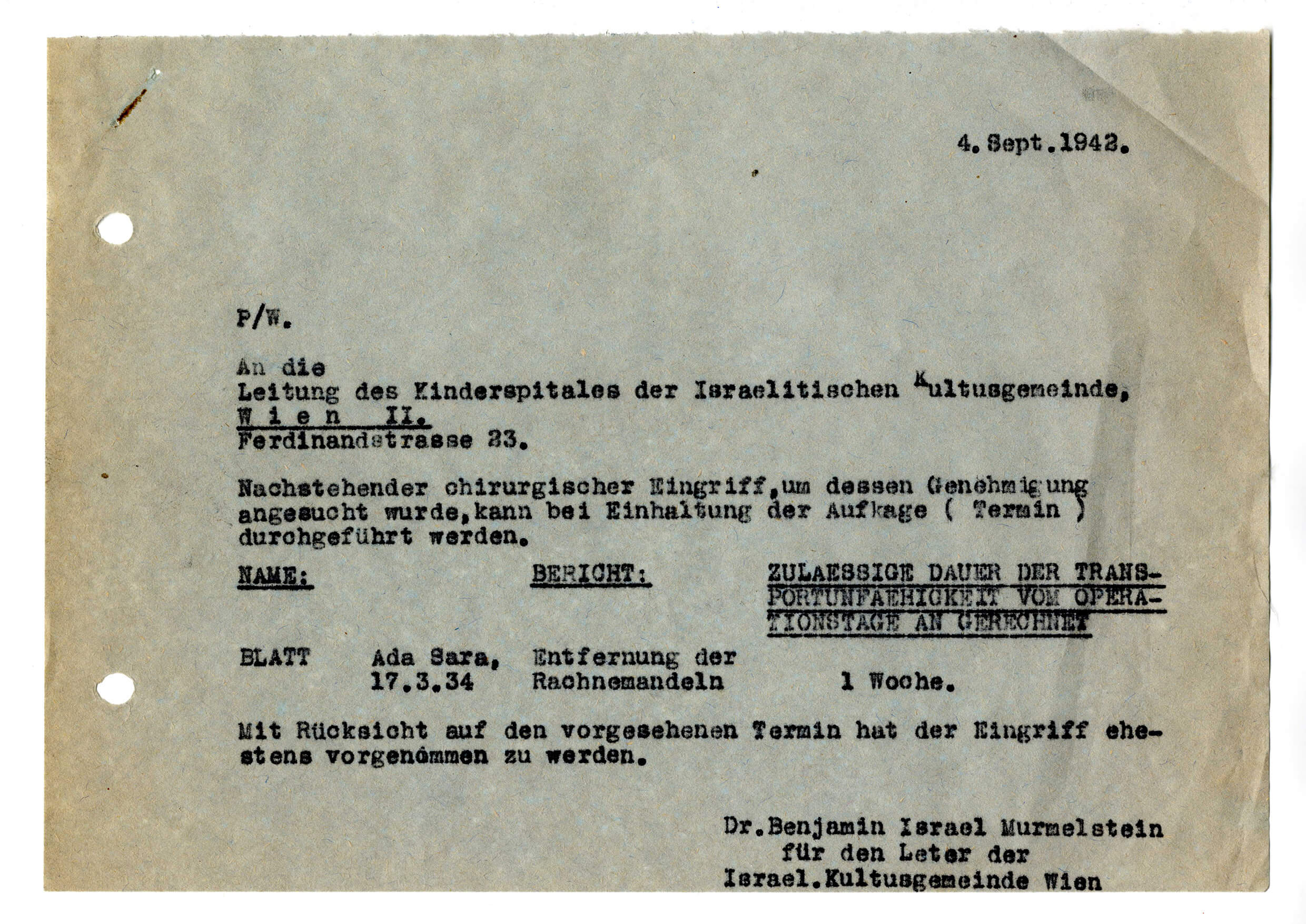

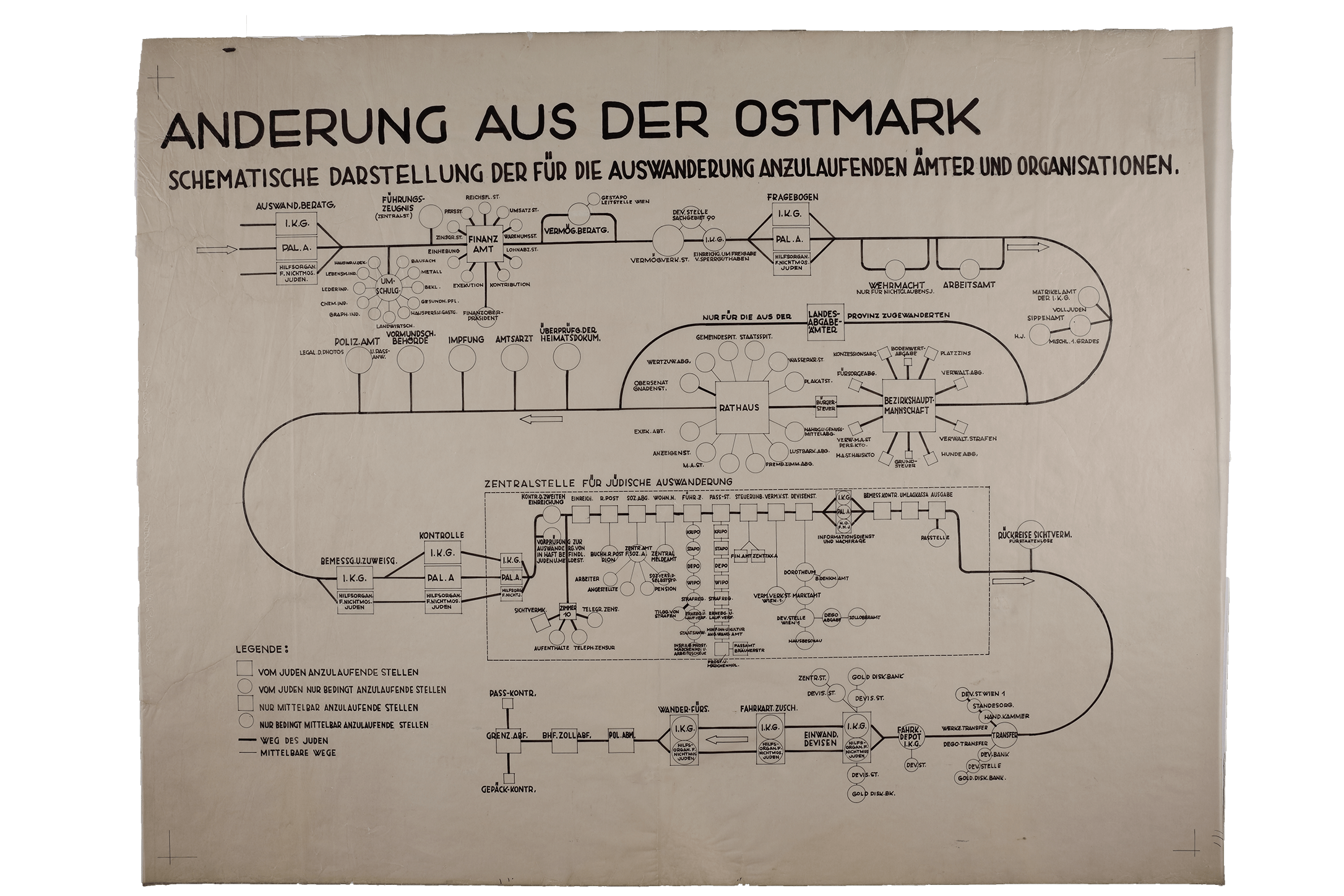

The Nazi regime quickly developed its own organisational structures to implement its persecution and extermination policies. At the instigation of Reinhard Heydrich, the Chief of the SS Security Service in Berlin, the “Central Office for Jewish Emigration” was set up in Vienna. Under the direction of Adolf Eichmann, a model was created for the systematic deprivation and expulsion of the Jewish population. From autumn 1939 onwards, the “Central Office” was also in charge of organising and implementing deportations from Austria. The Nazi regime coerced Jewish Community functionaries into playing an active role in this mass expulsion and, later on, in the deportation of Community members.

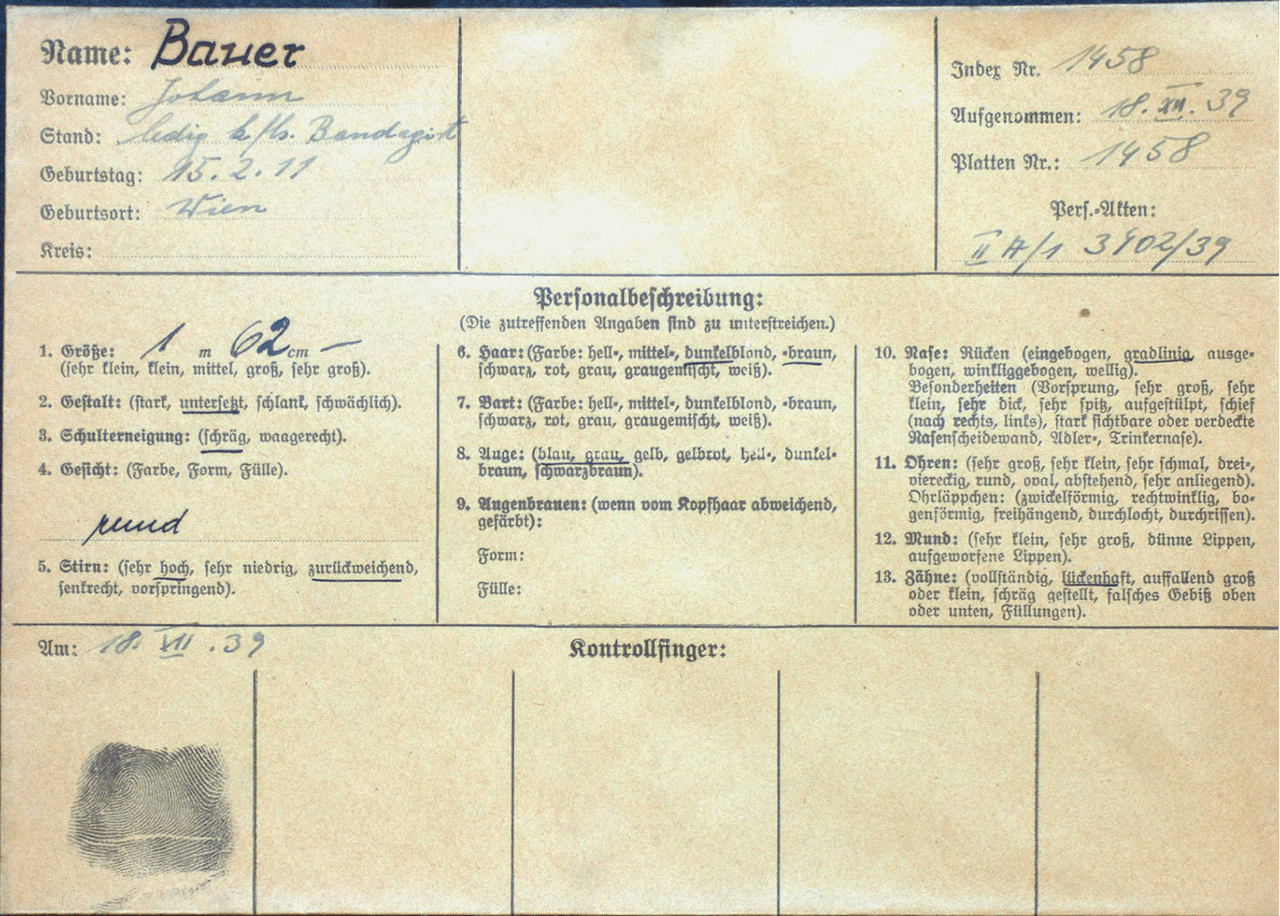

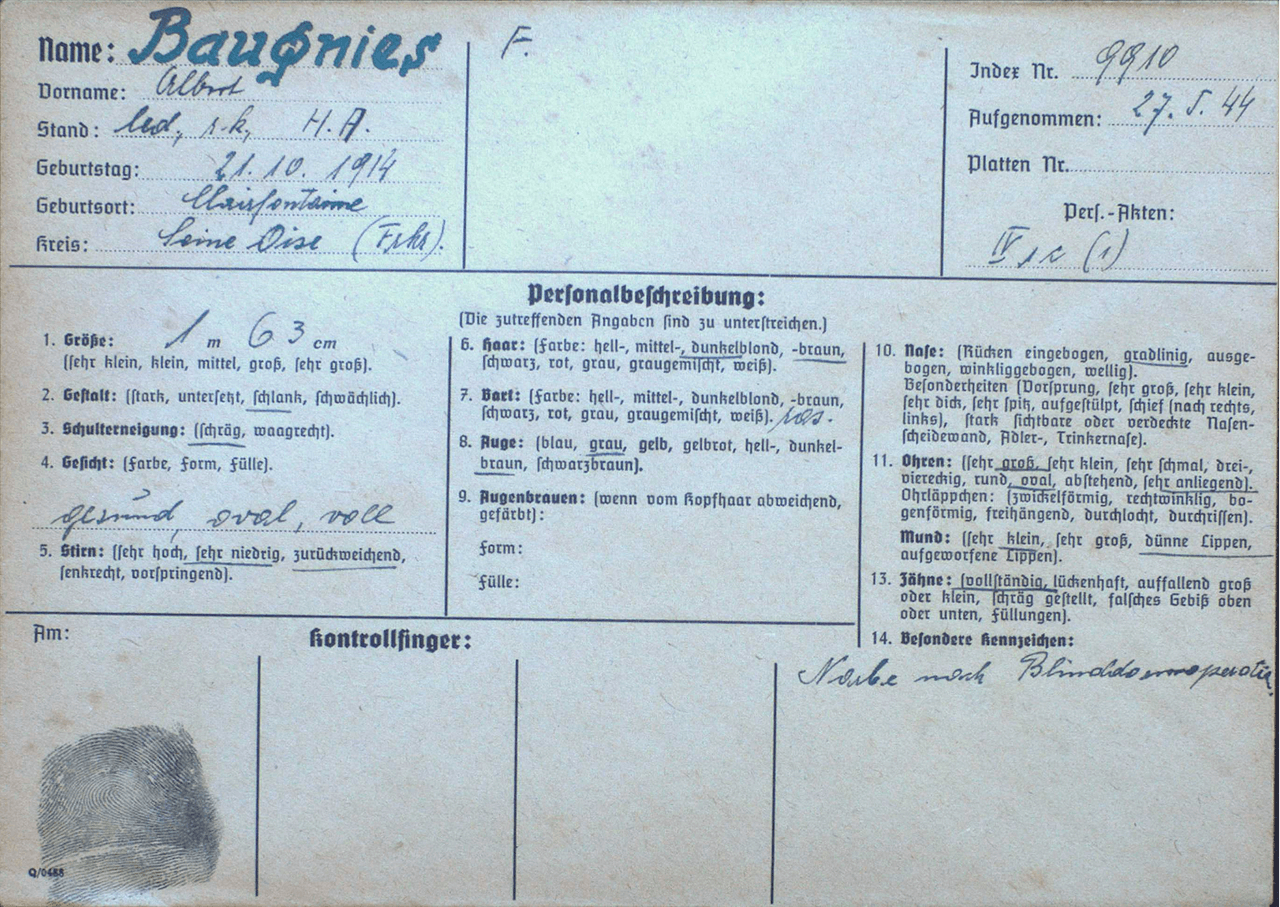

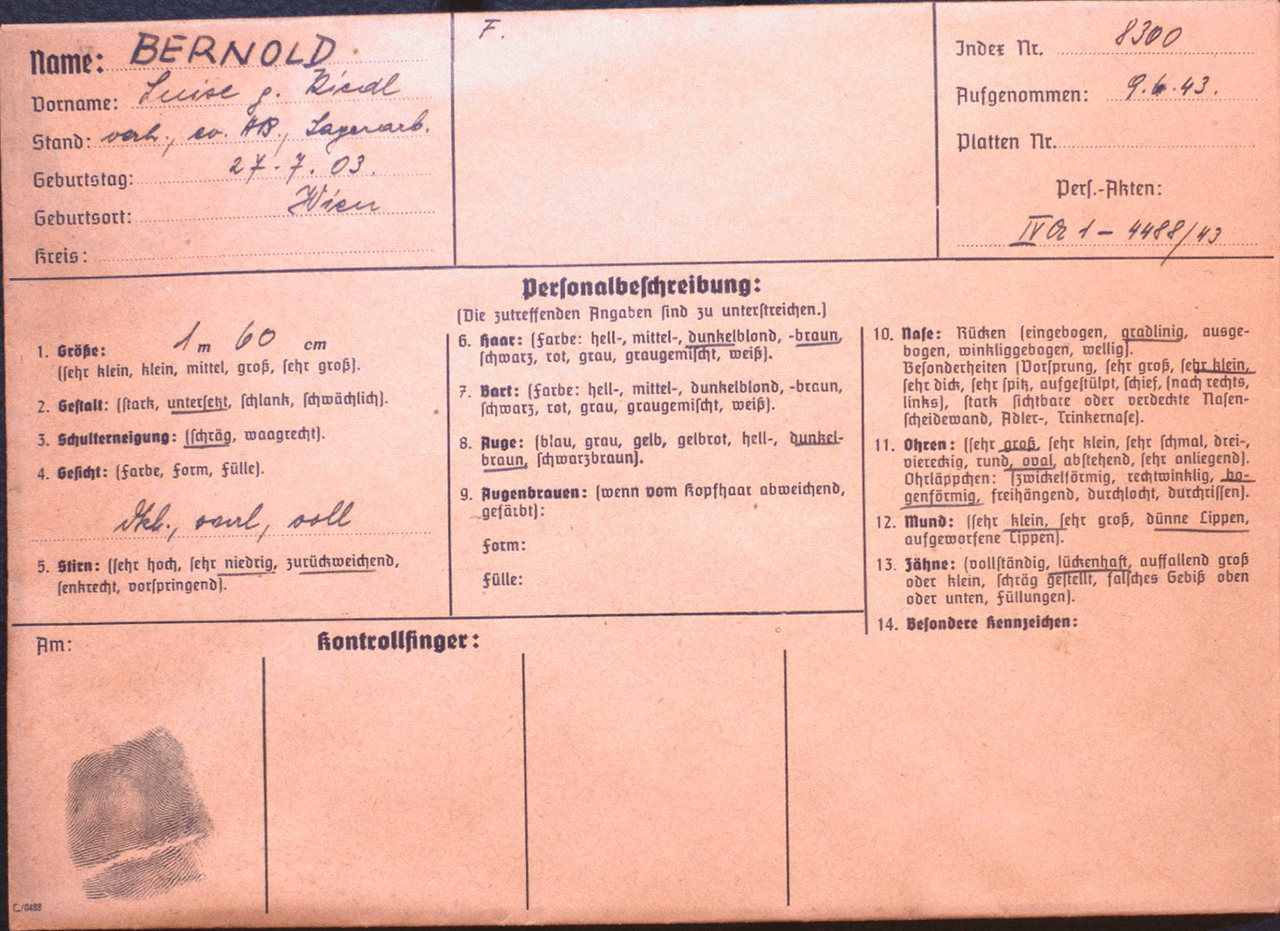

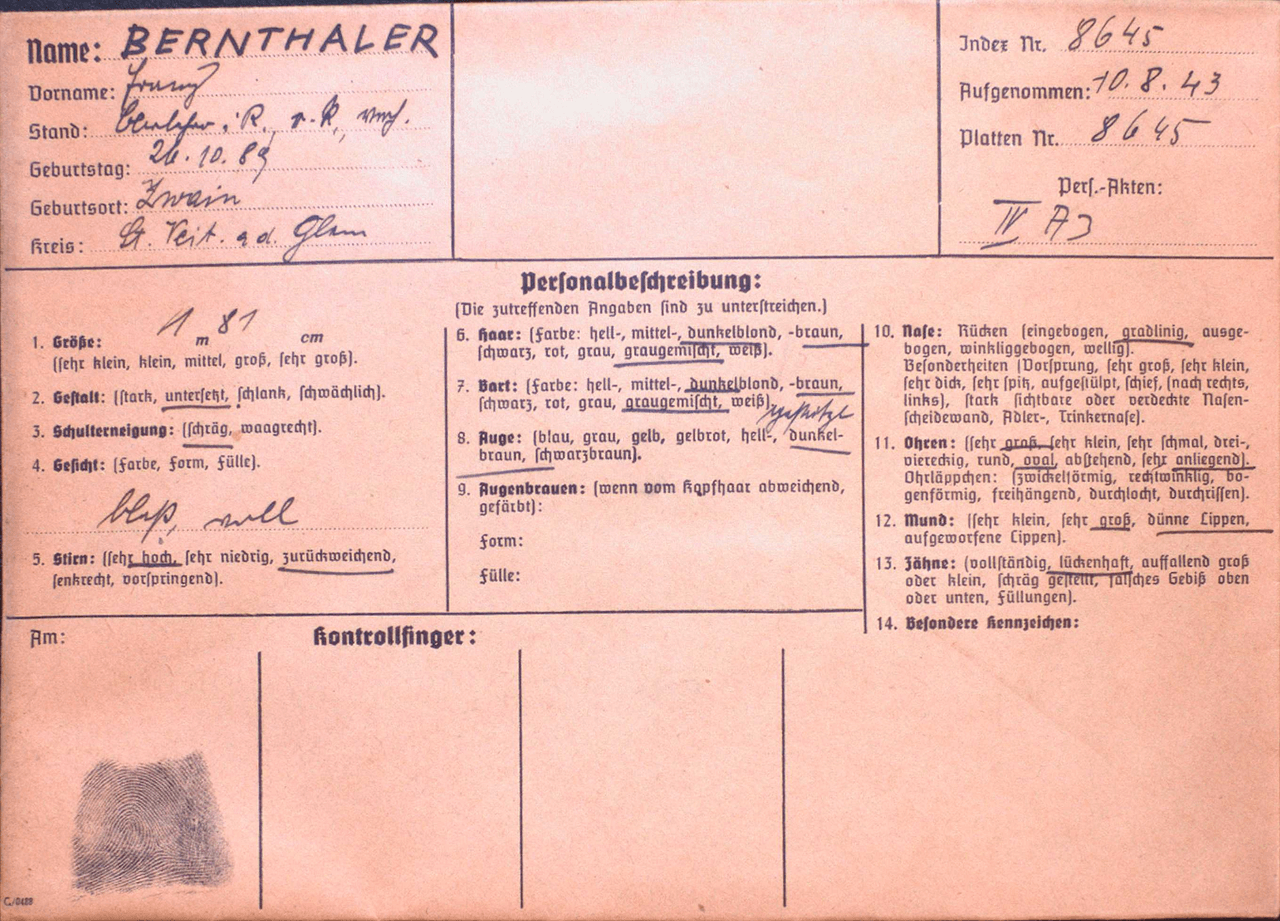

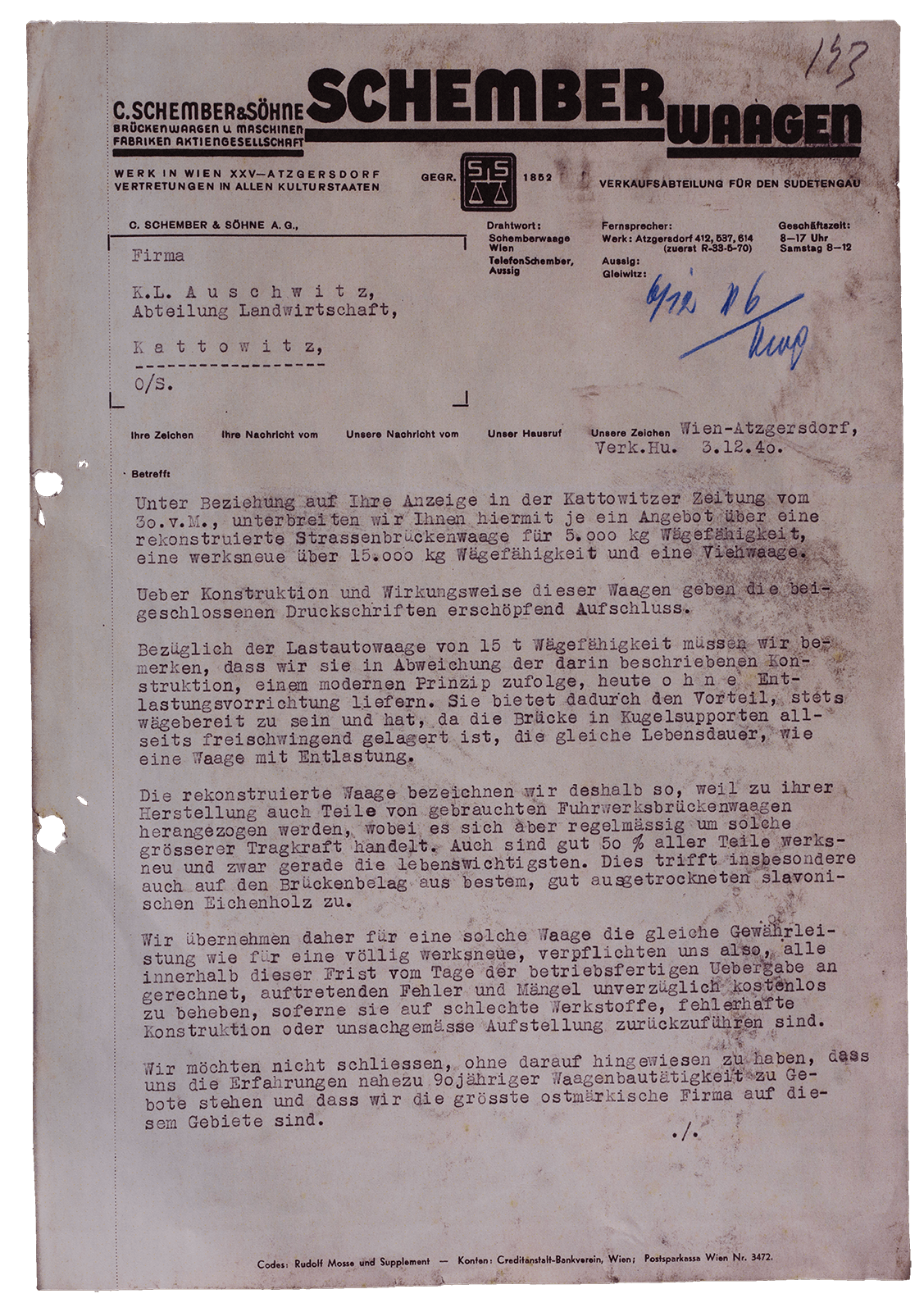

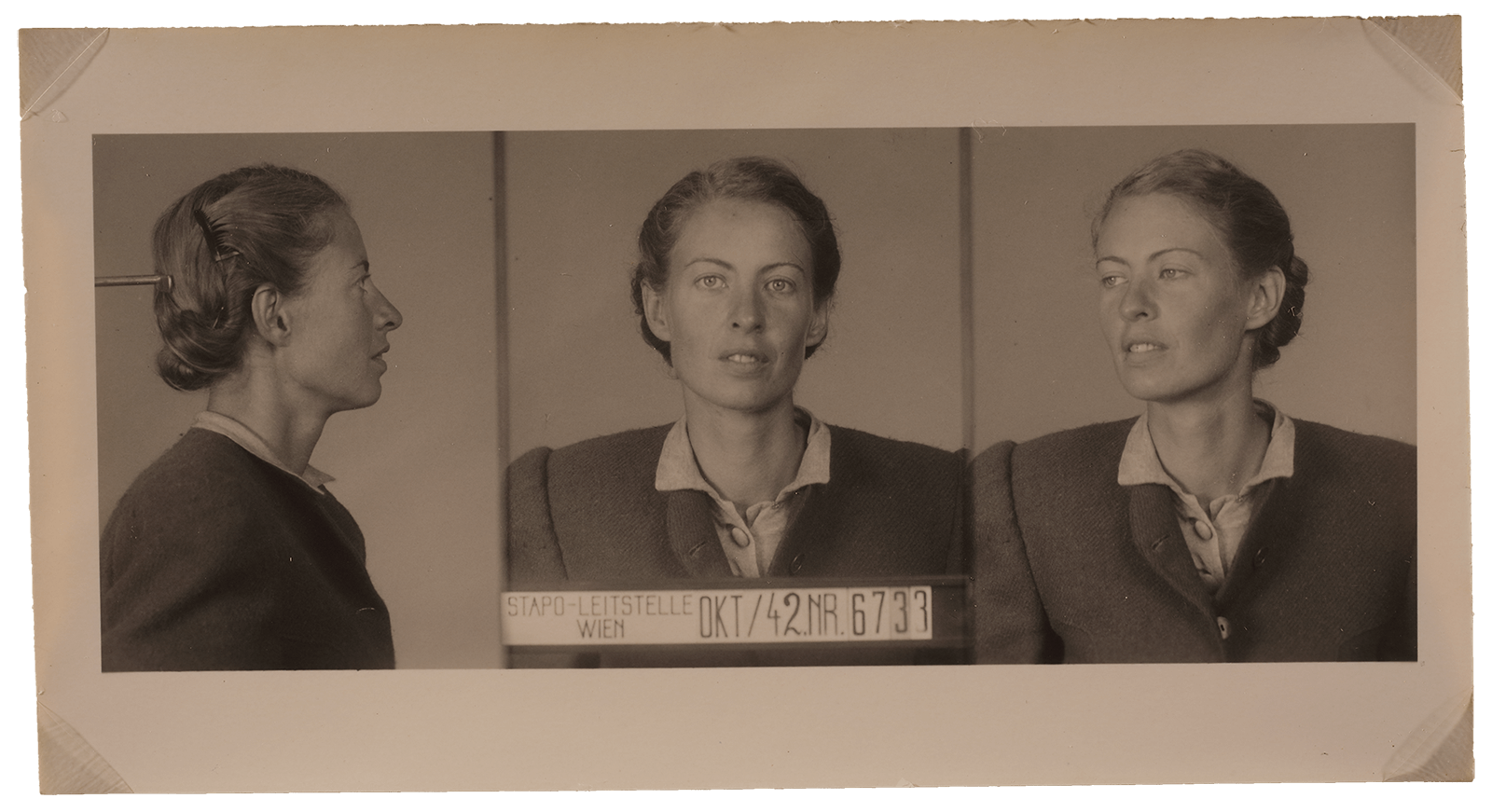

After the “Anschluss”, the Nazi terrorism of the 1930s was replaced by state-perpetrated terror. The Nazi regime quickly created institutional structures to implement its violent measures. The Secret State Police (Gestapo) Vienna, for example, took up its work at the beginning of April 1938 in the former Hotel Métropole. With over 900 employees, it was the largest state police headquarters in the German Reich. On 1 April, the first Austrian prisoners, mainly prominent figures from the fields of politics, culture and the arts, were deported from Vienna to Dachau concentration camp.

With the outbreak of war in 1939, the Reich Security Main Office in Berlin, established on the orders of Heinrich Himmler, became the main instrument for persecuting people who had been declared opponents of the Nazi regime for “racial”, political and ideological reasons. In 1943, the Austrian Ernst Kaltenbrunner was appointed Chief of the Reich Security Main Office, which put him at the head of the extermination machinery. The persecution measures, expulsions, disenfranchisement and dehumanisation were implemented systematically and aimed, first and foremost and on a vast scale, at the Jewish population and political opponents.

After the “Anschluss”, the hostile measures taken against the Jewish population took on many forms, such as public humiliation, arrests and physical assaults, and the devastation of shops and institutions. The “illicit aryanisations” also commenced immediately: Nazi gangs roamed the streets looting and plundering, and neighbours and business partners took advantage of the opportunity to enrich themselves at the expense of the Jewish population.

The pogrom atmosphere and uncontrolled looting of Jewish property led the Nazi regime to put legal and administrative measures in place to enable the “orderly” financial disenfranchisement of the Jews. At the instigation of Reinhard Heydrich, the Chief of the SS Security Service in Berlin, the “Central Office for Jewish Emigration” was set up in Vienna. Under the direction of Adolf Eichmann, it created a model for the systematic plunder and expulsion of the Jewish population. With the establishment of the Vermögensverkehrsstelle (Property Transaction Office), dispossessions were legalised and carried out nationwide, and the “spoils of aryanisation” secured for the Nazi regime and its supporters.

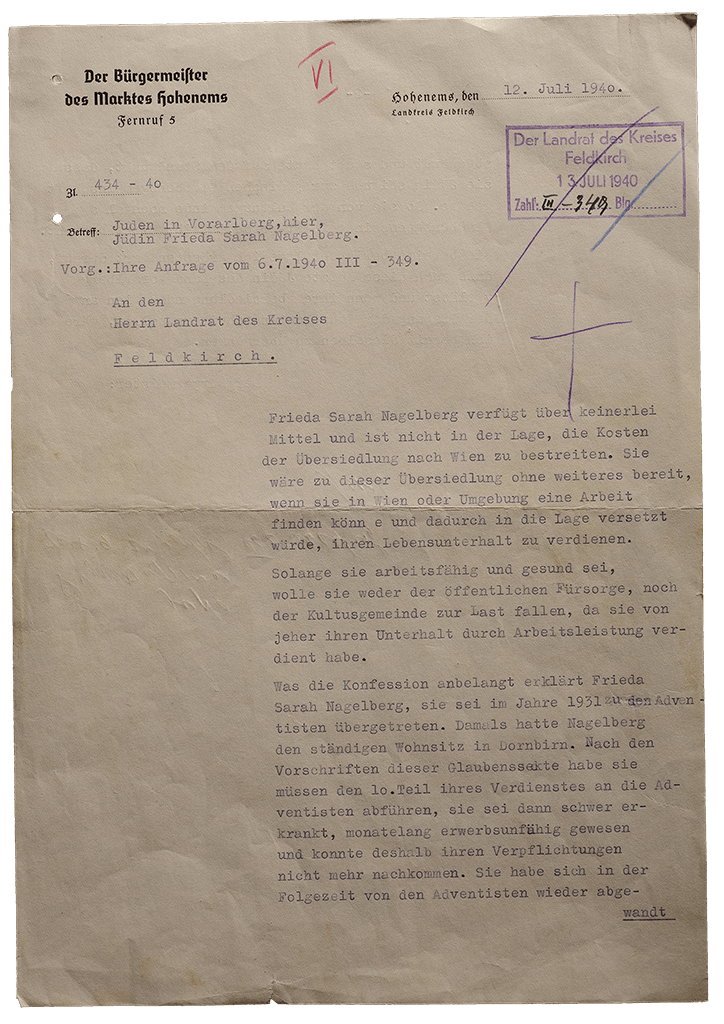

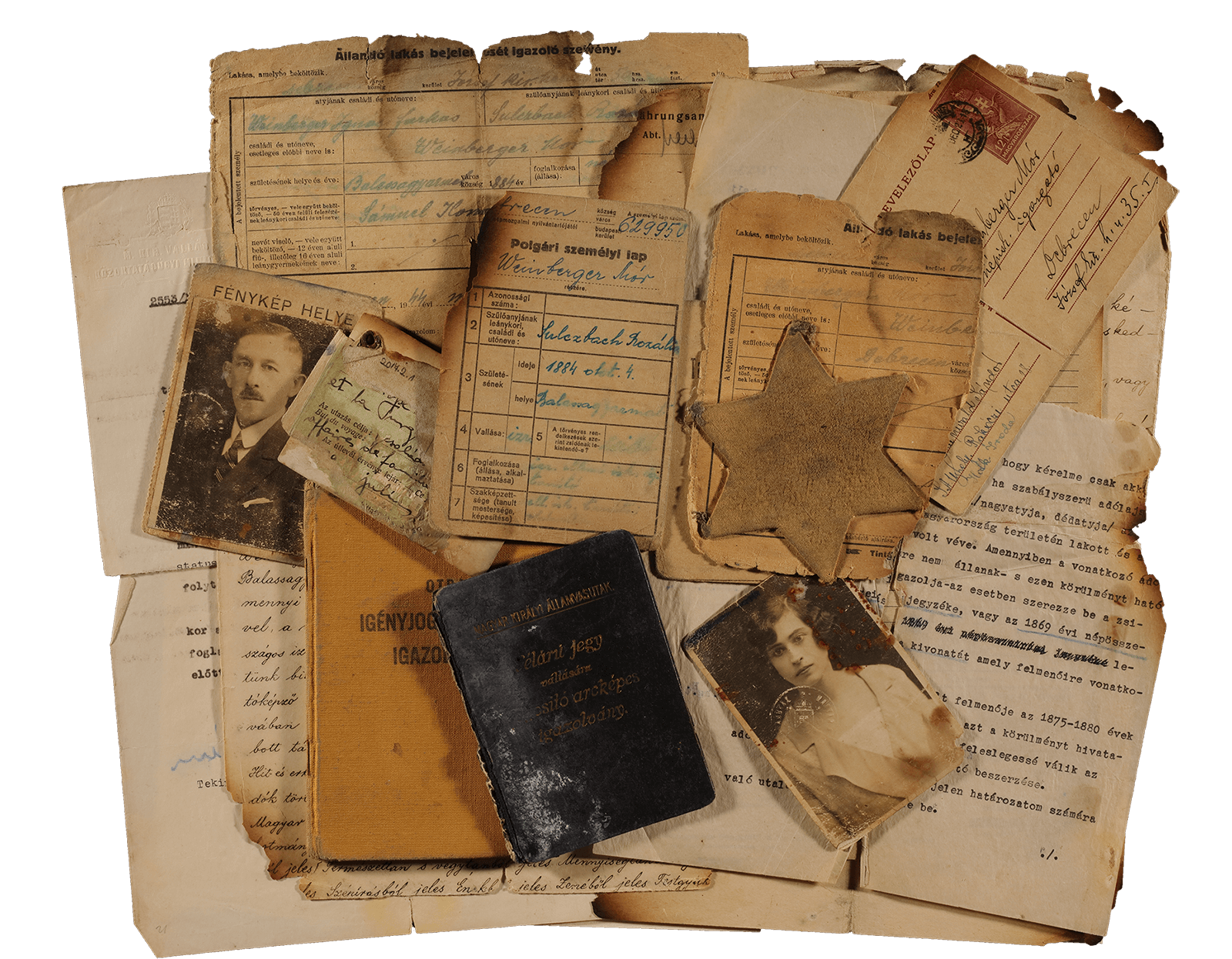

The legal basis for the marginalisation of the Jewish population – occupational bans, revocation of academic titles, expropriations, discrimination and stigmatisation, deprivation of housing and expatriation – was created by passing extraordinary legislation. Following the confiscation of their entire possessions, tens of thousands of Austrian Jews attempted to flee Austria. With the outbreak of war, it became virtually impossible to escape. From autumn 1939 onwards, the “Central Office” was also in charge of organising and implementing deportations from Austria. In a particularly perfidious move, the so-called Judenräte or Ältestenräte (“Jewish Councils”) were forced to cooperate.

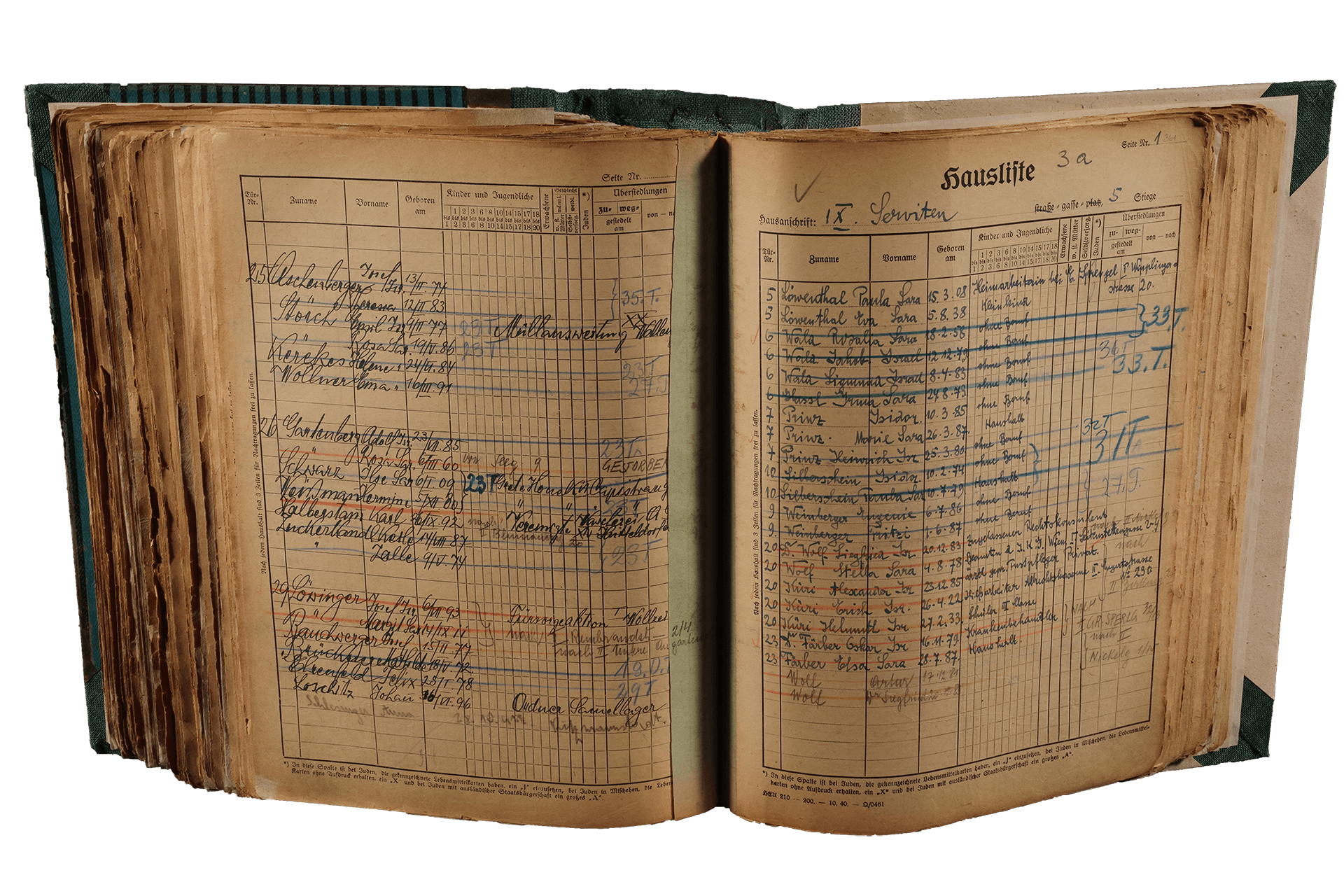

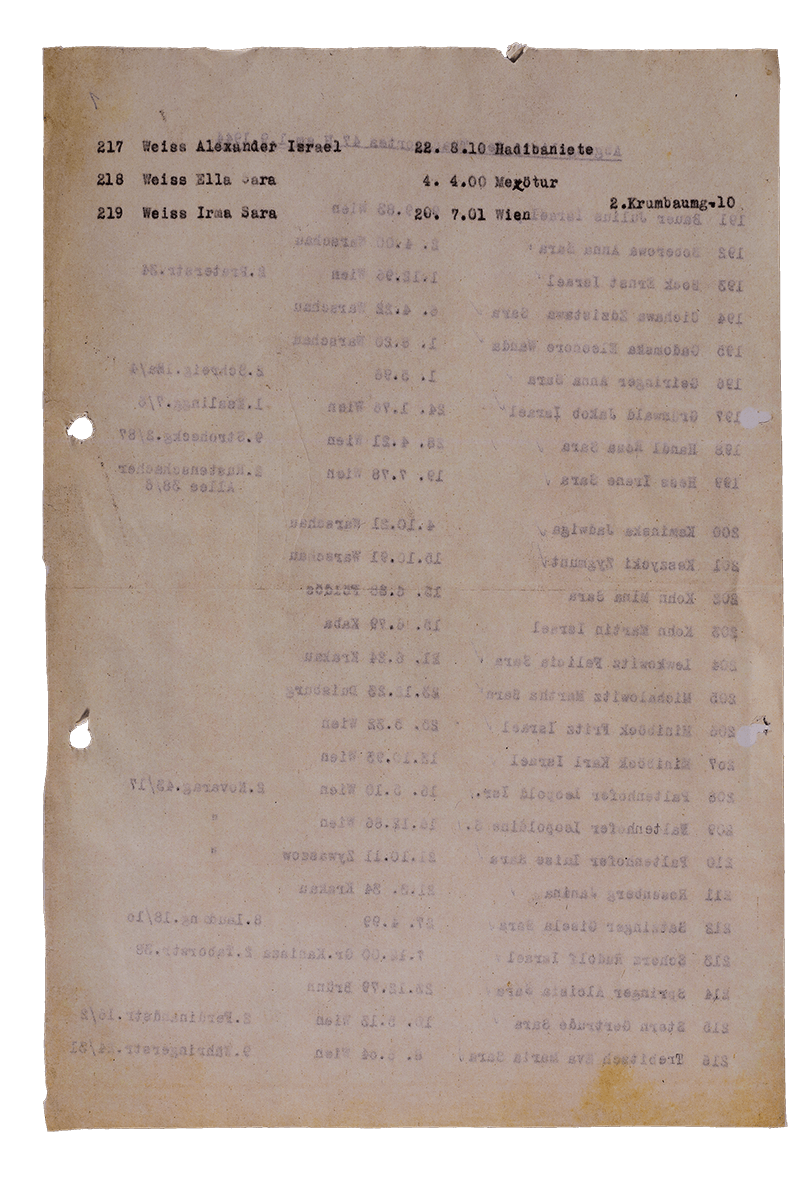

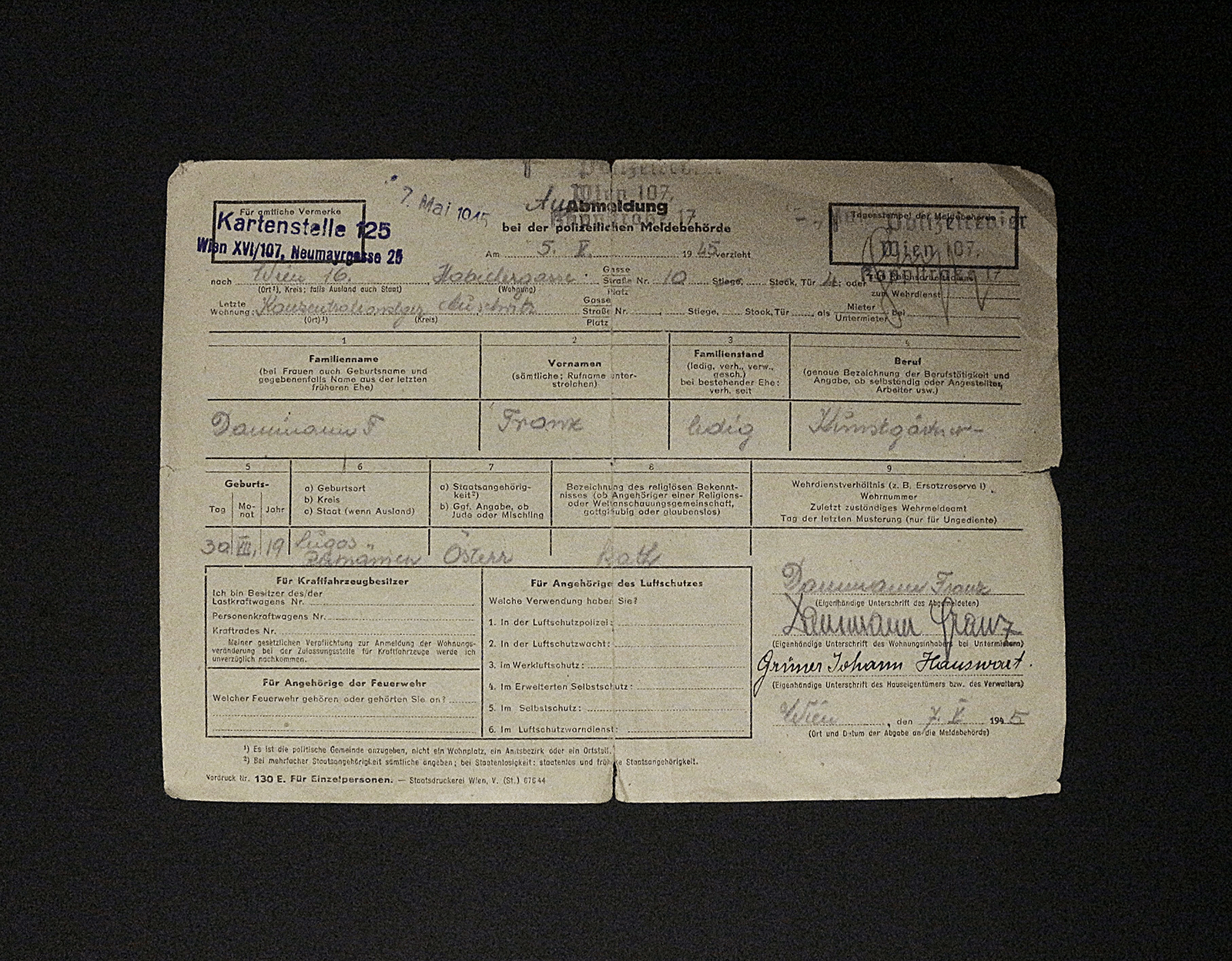

Before the deportations were carried out, numerous measures were taken to register the Jewish population. Jews from all over Austria were forcibly relocated to Vienna and, like the Viennese Jews, concentrated in shared apartments. The first deportations were carried out immediately after the invasion of Poland in 1939. Over 1,000 Jews with Polish citizenship were held at the Prater Stadium for several days and mistreated before finally being deported to Buchenwald. In November 1939, the so-called Nisko transport took place, the first deportation to the Generalgouvernement.

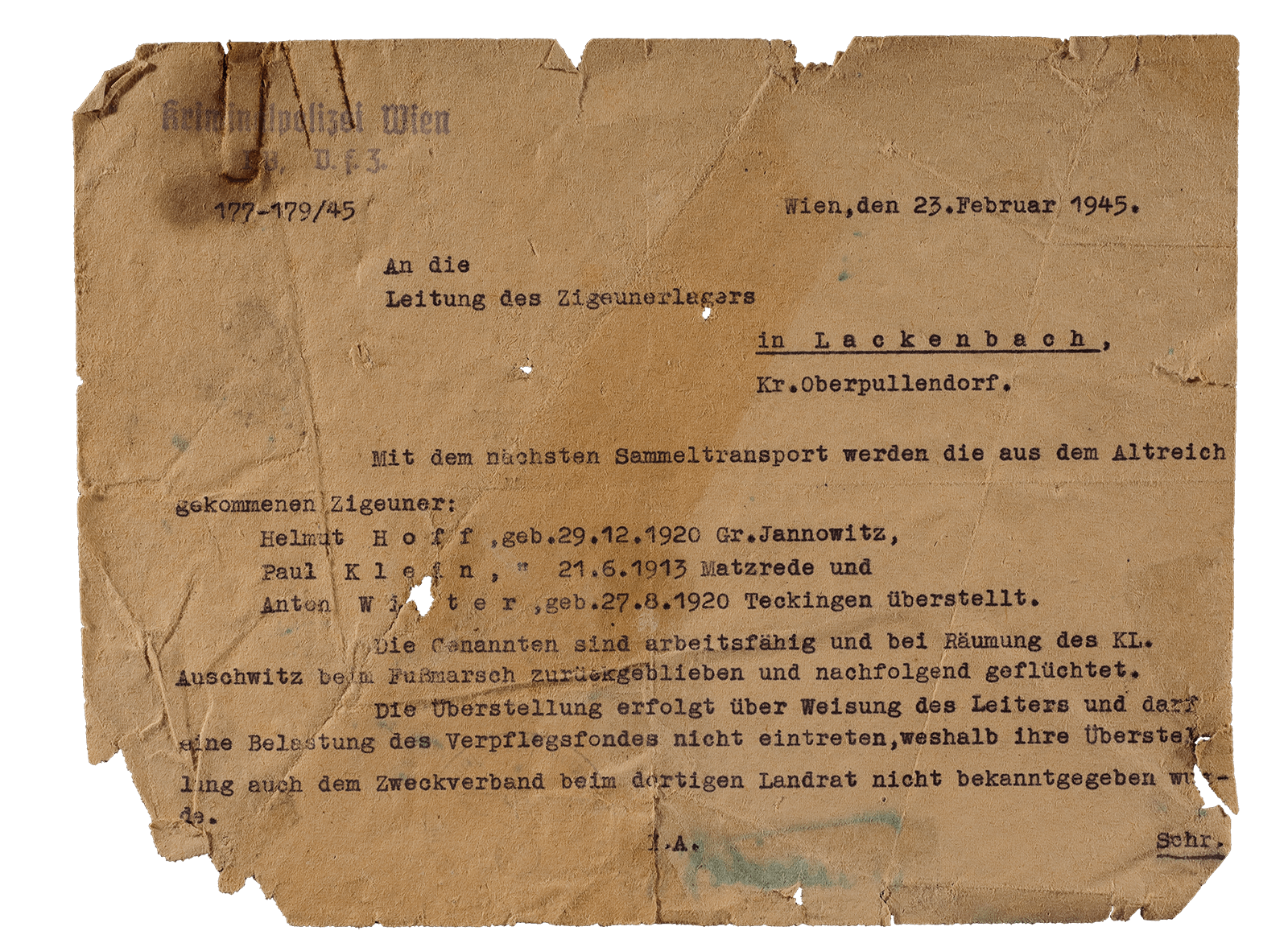

The “Central Office” worked closely with the Viennese Schutzpolizei (“Protection Police”) to deport the Jews. The Austrian Roma and Sinti were for the most part initially interned in concentration camps designated as “assembly camps”, such as Lackenbach, and deported from there. From 1943 they were also deported to Auschwitz.

The majority of Austrian Auschwitz victims had previously been interned in other concentration camps or were deported to Auschwitz from assembly camps and ghettos. Many were brought there from other countries, particularly from France.

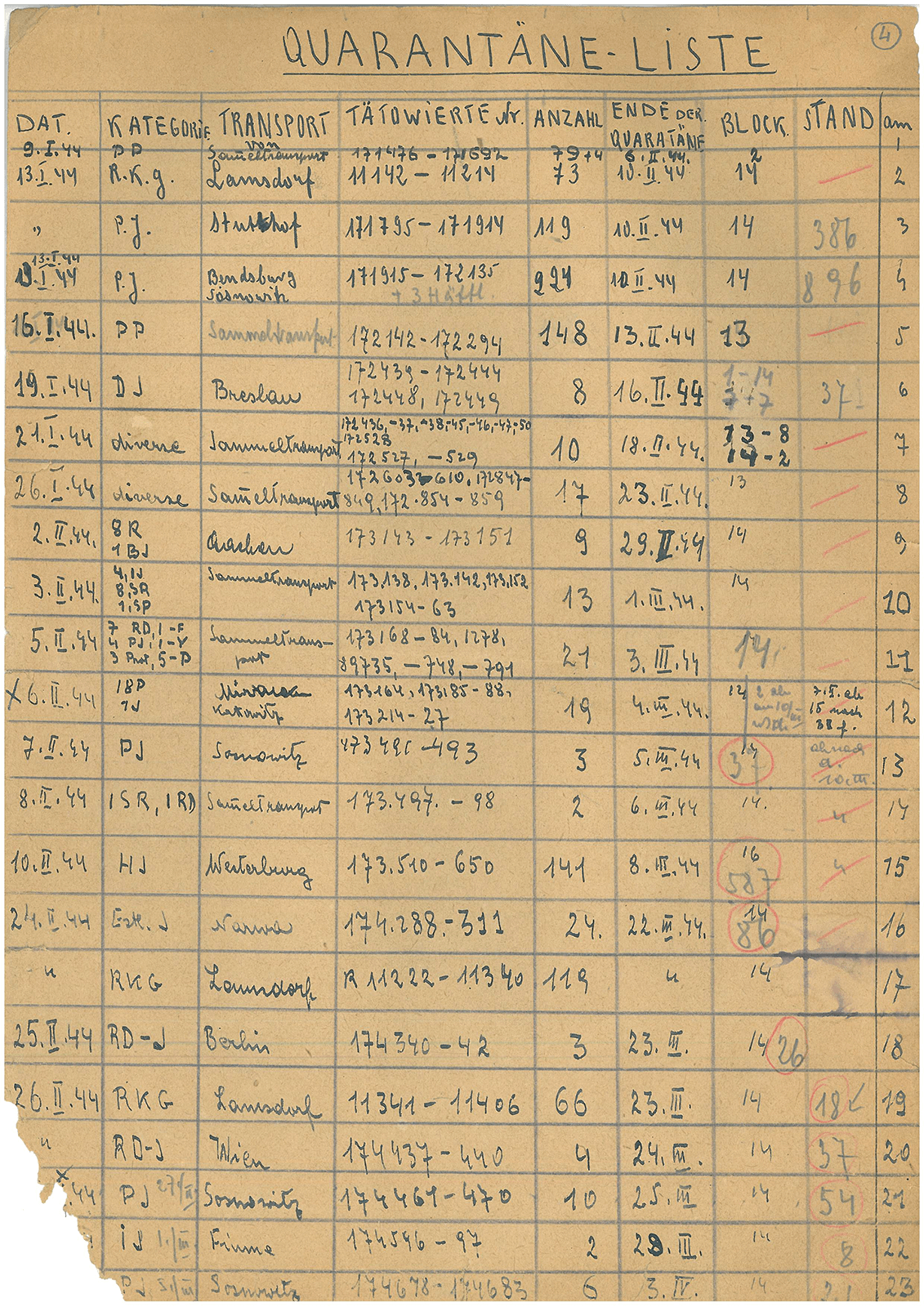

People persecuted for being Jews as defined by the “Nuremberg Laws”, political dissidents and members of the Resistance, Roma and Sinti, Jehovah's Witnesses and people categorised by the Nazi system as homosexuals, criminals or asocial were deported from Austria, almost 8,000 were brought directly to Auschwitz. Over 4,000 Austrians were taken to Auschwitz via Theresienstadt concentration camp, and another 6,000 from the occupied territories of Europe or other concentration camps. Upon arrival they were categorised depending on the grounds for their persecution. This categorisation determined their position in the camp hierarchy and hence also their living conditions and chances of survival.

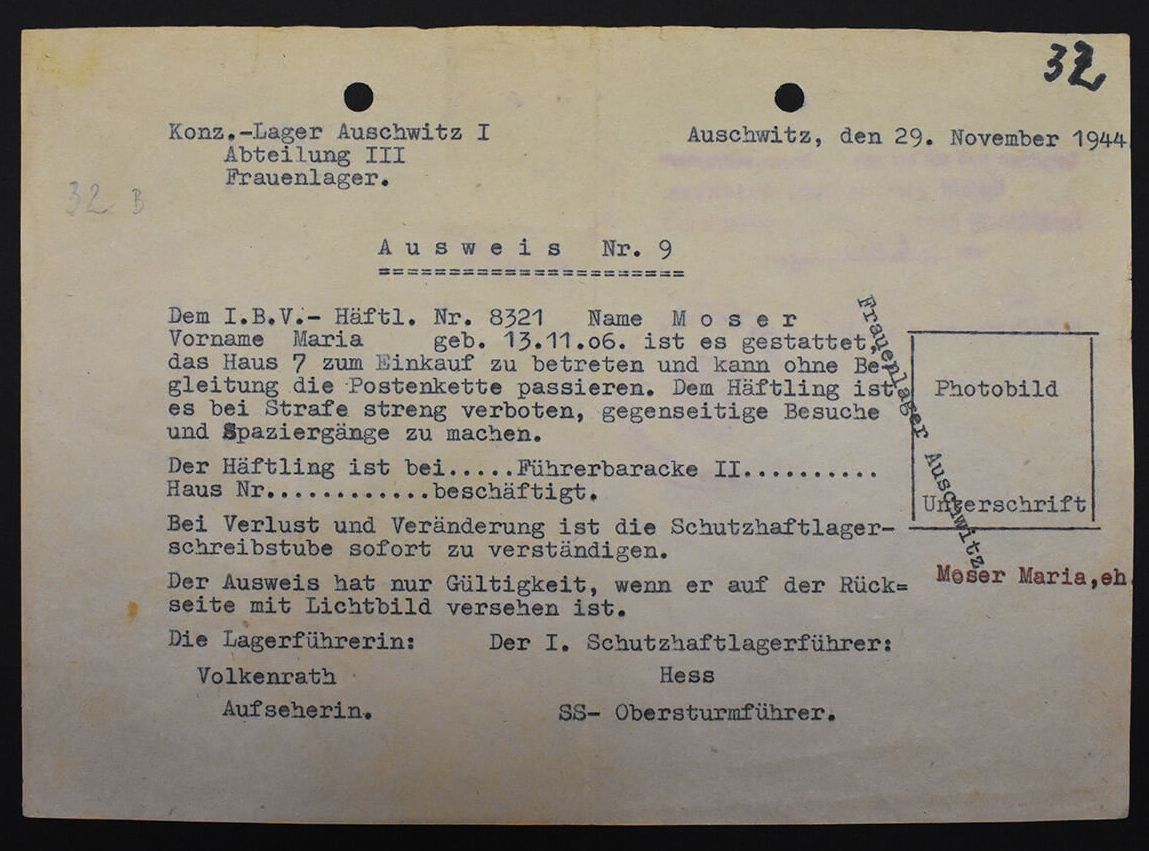

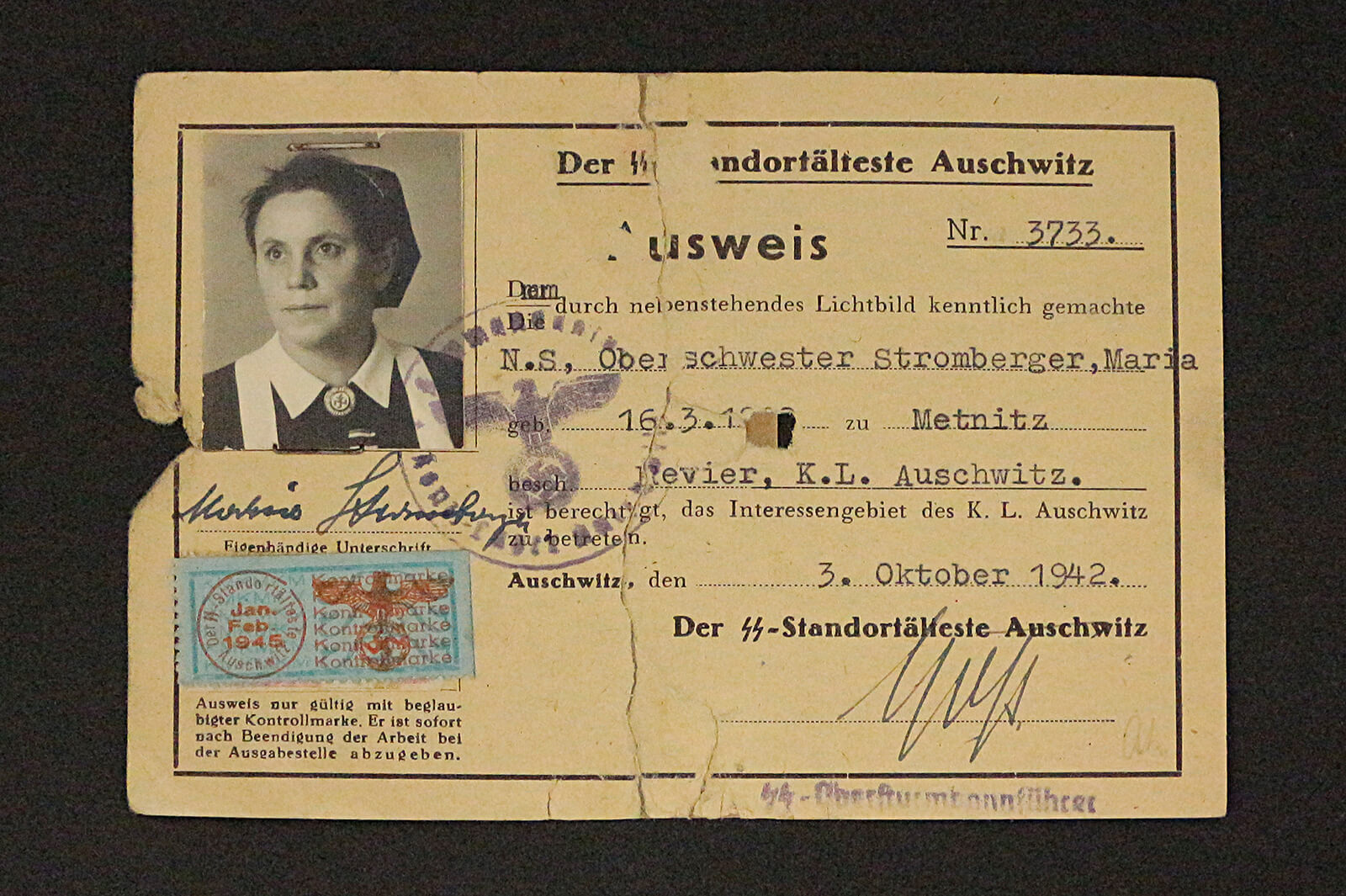

The SS generally put Jews through the “selection” process immediately upon arrival, when it was decided who would go straight to the gas chambers and who would be admitted to the camp. Austrian SS members, including a number of women, were involved in the system of dehumanization, enslavement and murder of the inmates in a wide variety of capacities.

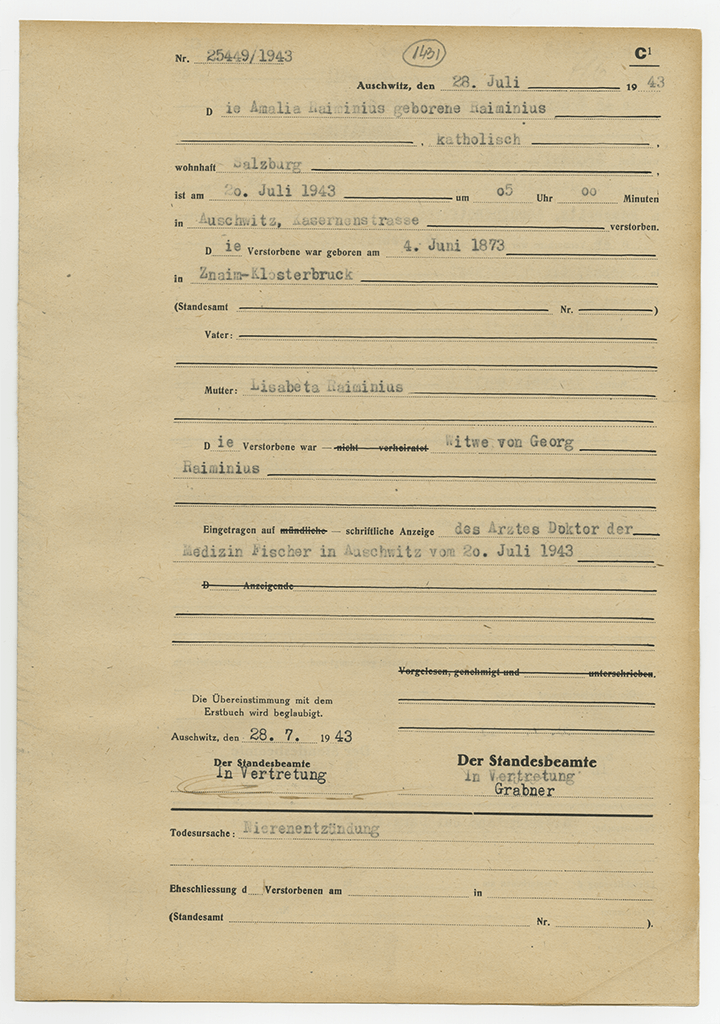

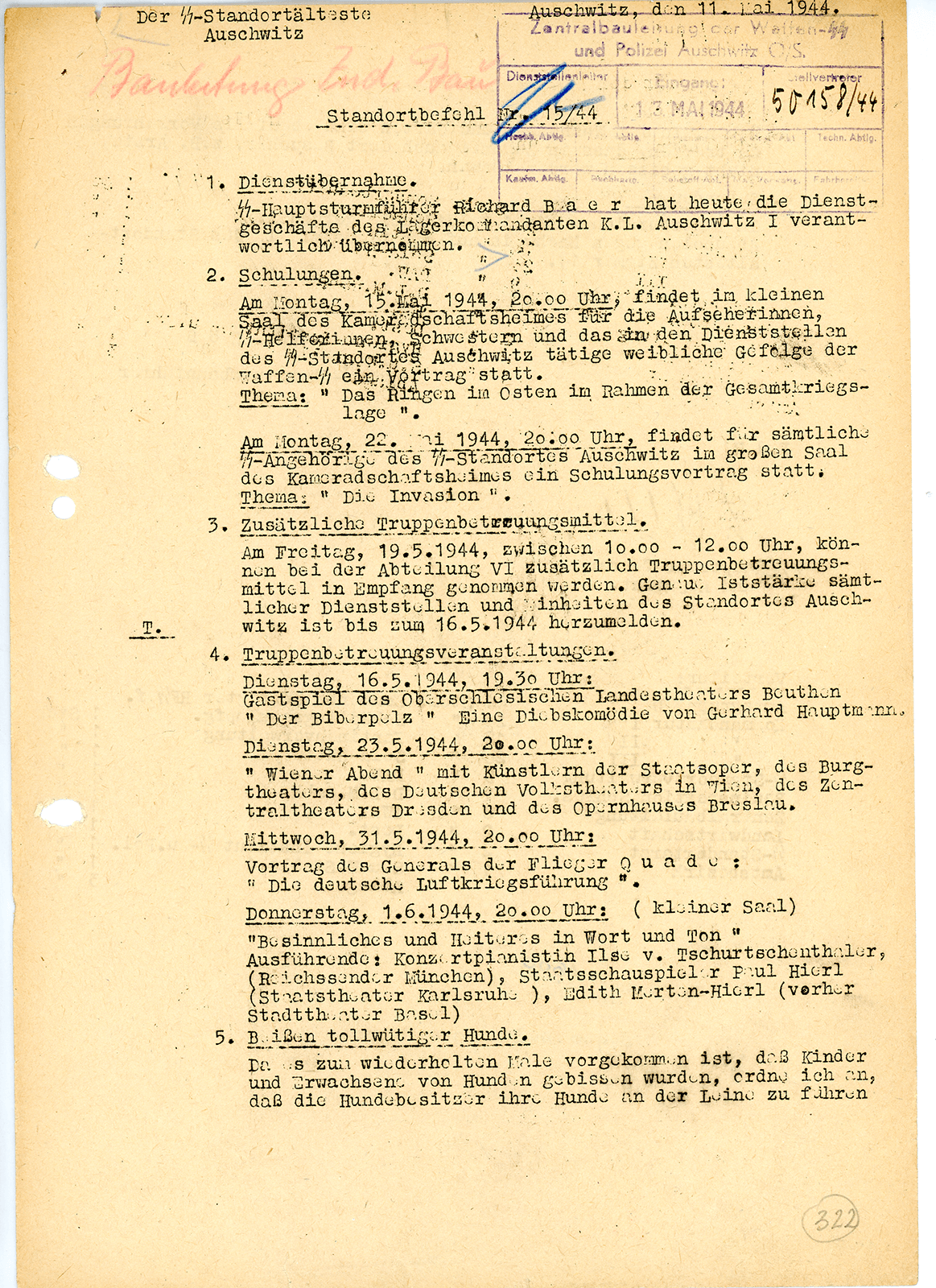

Auschwitz had a strict hierarchy. First and foremost, the camp administration dictated the lives, conditions of imprisonment and death of the deportees. However, the guards, the camp Gestapo, concentration camp doctors and other divisions were also part of this structure of terror. Austrians held leading positions at the camp, for example Maximilian Grabner and Hans Schurz as Heads of the camp Gestapo and Maria Mandl as Head Guard of the women’s camp.

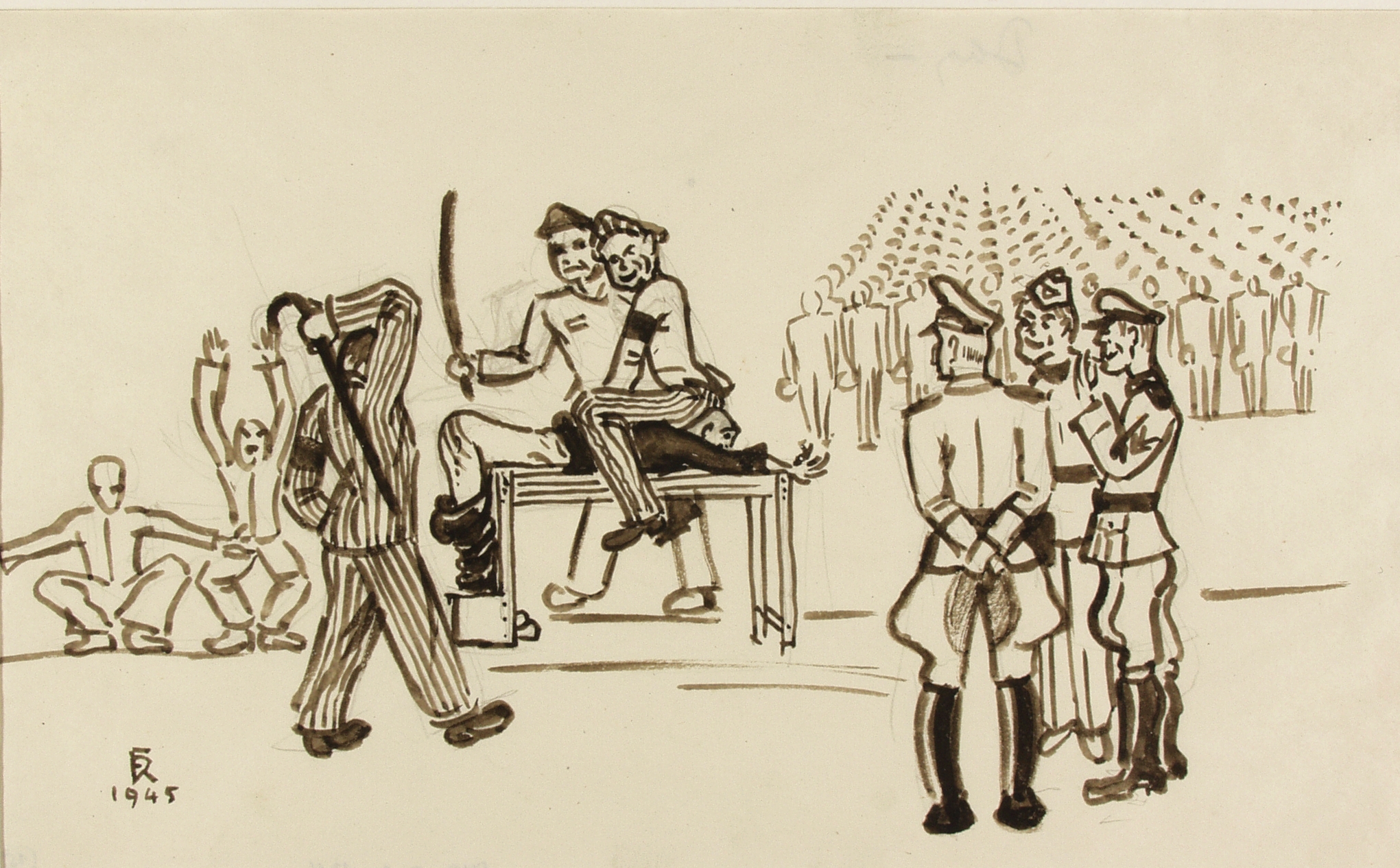

The concentration camp system also relied on a hierarchy among the inmates, who were divided into different categories. At the top of this hierarchy were the kapos, who acted as intermediaries between the prisoners and the guards and were responsible for guarding and disciplining the prisoners. Prisoner functionaries were given individual “privileges”, such as extra food rations, permission to receive parcels, to smoke or to visit the prisoners’ brothel. Jewish prisoners and Roma and Sinti were at the very bottom of the prisoner hierarchy. Despite this categorisation, ultimately the lives of all prisoners were constantly at risk.

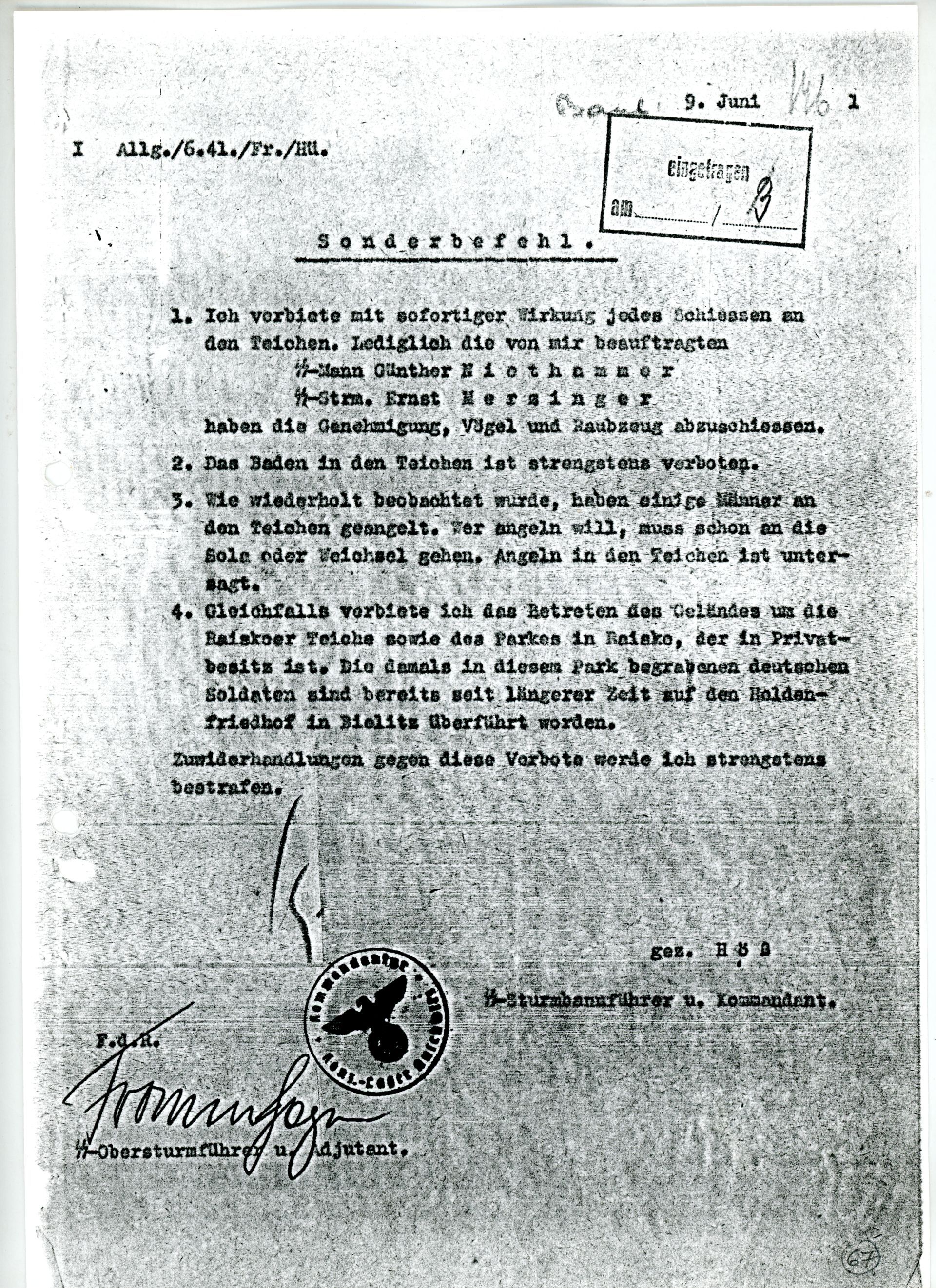

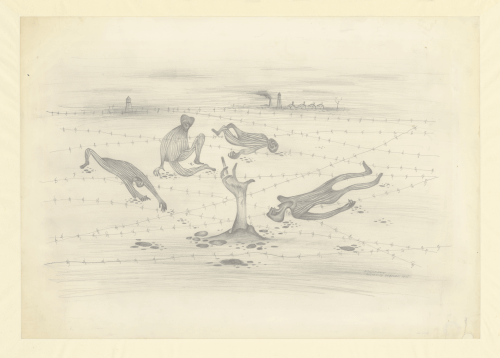

The Auschwitz camp complex existed for a period just short of five years, and during that time the tasks performed there and the conditions changed repeatedly. Efforts to keep the industrial-scale extermination running smoothly were often impeded by improvisation and chaos. Like at other extermination sites, the genocide was to take place covertly. To achieve this, the Interessengebiet des KZ Auschwitz (“Auschwitz Concentration Camp Area of Interest”), a restricted area controlled by the SS, was established in 1941, covering approximately 40 km2.

The constantly changing circumstances at Auschwitz also led to the permanent expansion and reorganisation of the camp complex. From March 1942 onwards, for example, a separate “women’s camp” for newly arrived female prisoners and a so-called gypsy camp for Roma and Sinti were created in Auschwitz-Birkenau; from September 1943 onwards the “Theresienstadt family camp” was also set up there for thousands of Jews arriving from Theresienstadt concentration camp. A separate concentration camp was built on behalf of the German industrial sector, Auschwitz III-Monowitz, where Auschwitz inmates were put to work as slave labourers.

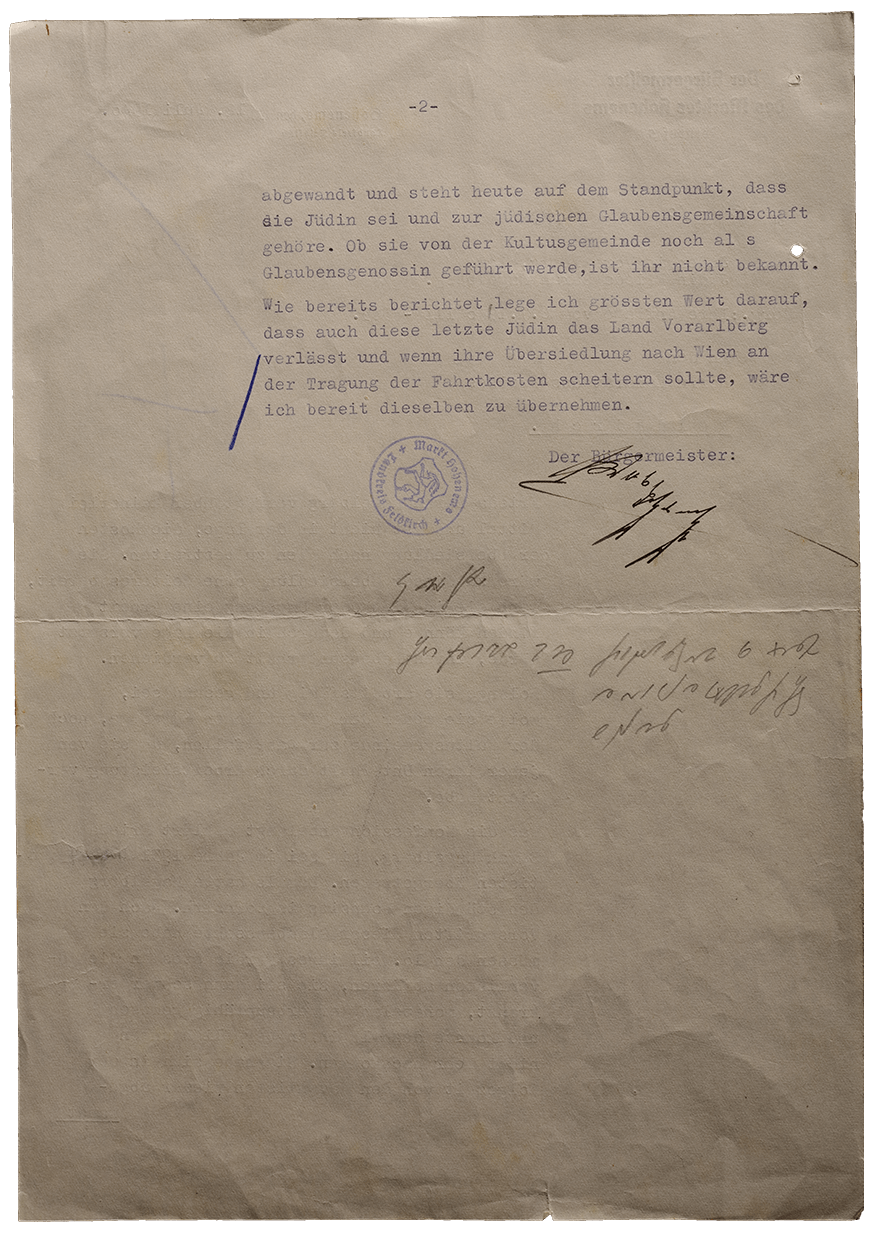

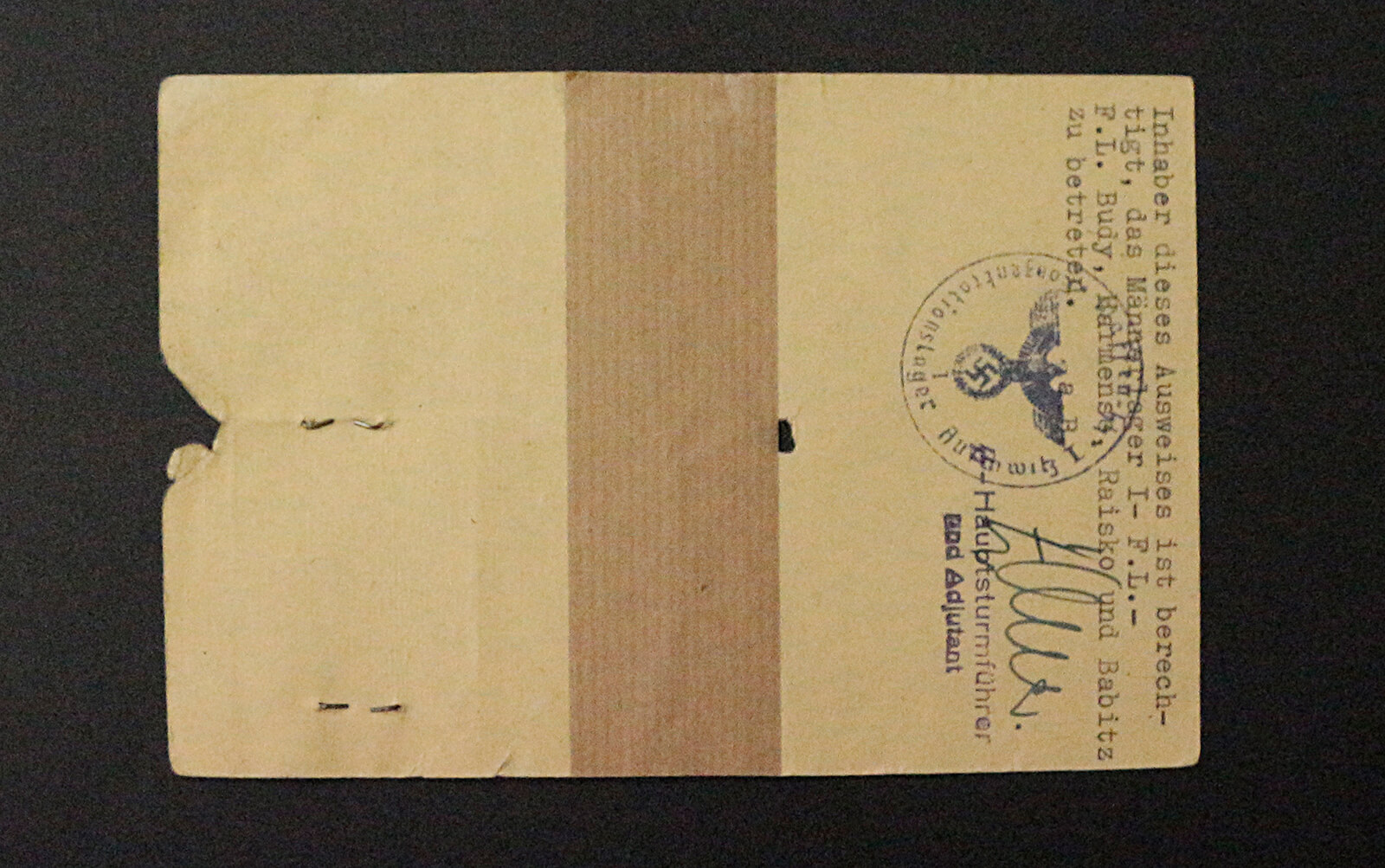

Exploitation in the form of slave labour, looting, liquidation and murder underpinned the economy of the concentration camp system. For this purpose, a distinction was made between people who were allowed to live to perform slave labour and those who were sent to their death. Absolutely everything was put to use to serve the economic interests of the German Reich – the deportees’ belongings and the labour of those who could still work. Even the corpses of the murdered, their hair or gold teeth, were put to further use. An important facility for the SS exploitation model was the “warehouse for personal effects” known as “Canada” – at that time a general synonym for wealth – where inmates sorted the belongings of the prisoners and the dead for further use. It was run by the Austrian Franz Schebeck.

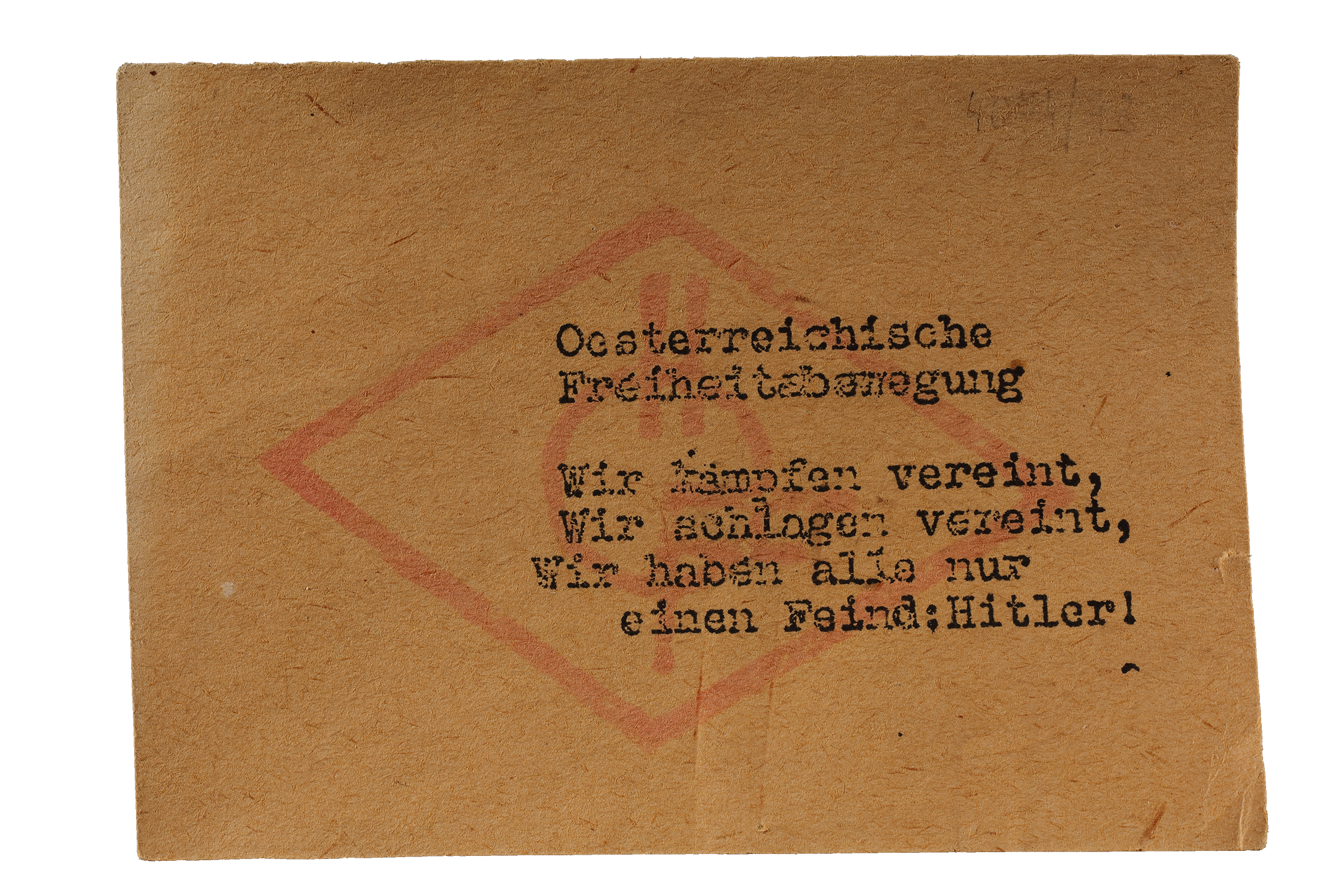

The Nazi regime demanded absolute compliance from the very outset. Apart from those who were excluded and persecuted from the start, the Austrian population consisted of those who fully subscribed to Nazi ideology; those who sought to benefit from the new political situation; passive bystanders or those who turned a blind eye; and a small minority who performed acts of resistance, either alone or as part of an organised group, in spite of the risk to their lives.

The ruling elite of the Nazi regime were responsible for the genocide. However, Nazi functionaries at all levels and many others played a part in executing the measures of persecution and carrying out atrocities in the run-up to Auschwitz.

The options available to those persecuted by the Nazi regime diminished rapidly. While escape was still an option at first, it became increasingly difficult. Once the deportations had begun, hiding or suicide were virtually the only options left.

The incorporation of Austria into the German Reich and the measures taken by the Nazi regime were met with approval by large sections of the Austrian population. The population consisted of those who fully subscribed to Nazi ideology or who sought to benefit from the new system; passive bystanders who looked on impassively or turned a blind eye; and those who were excluded and persecuted or who rejected the system and carried out acts of resistance against it. The ruling elite, which followed Adolf Hitler unquestioningly, felt legitimised to persecute, terrorise and commit mass murder. But it was the interplay between all levels – including a broad system of informants and spies at the bottom as well as highly dedicated individuals – that made it possible to implement the persecution measures. Above all else the disenfranchisement and deprivation of the Jewish population afforded numerous opportunities for personal enrichment and social advancement by eliminating the competition. In addition, new career opportunities arose for those loyal to the regime, often at the expense of others. Brutal assaults, arrests, acts of persecution and, later on, preparatory measures for the mass deportations became commonplace and occurred in full view of the population. Many looked on; others who did not approve of the injustices looked away without taking action.

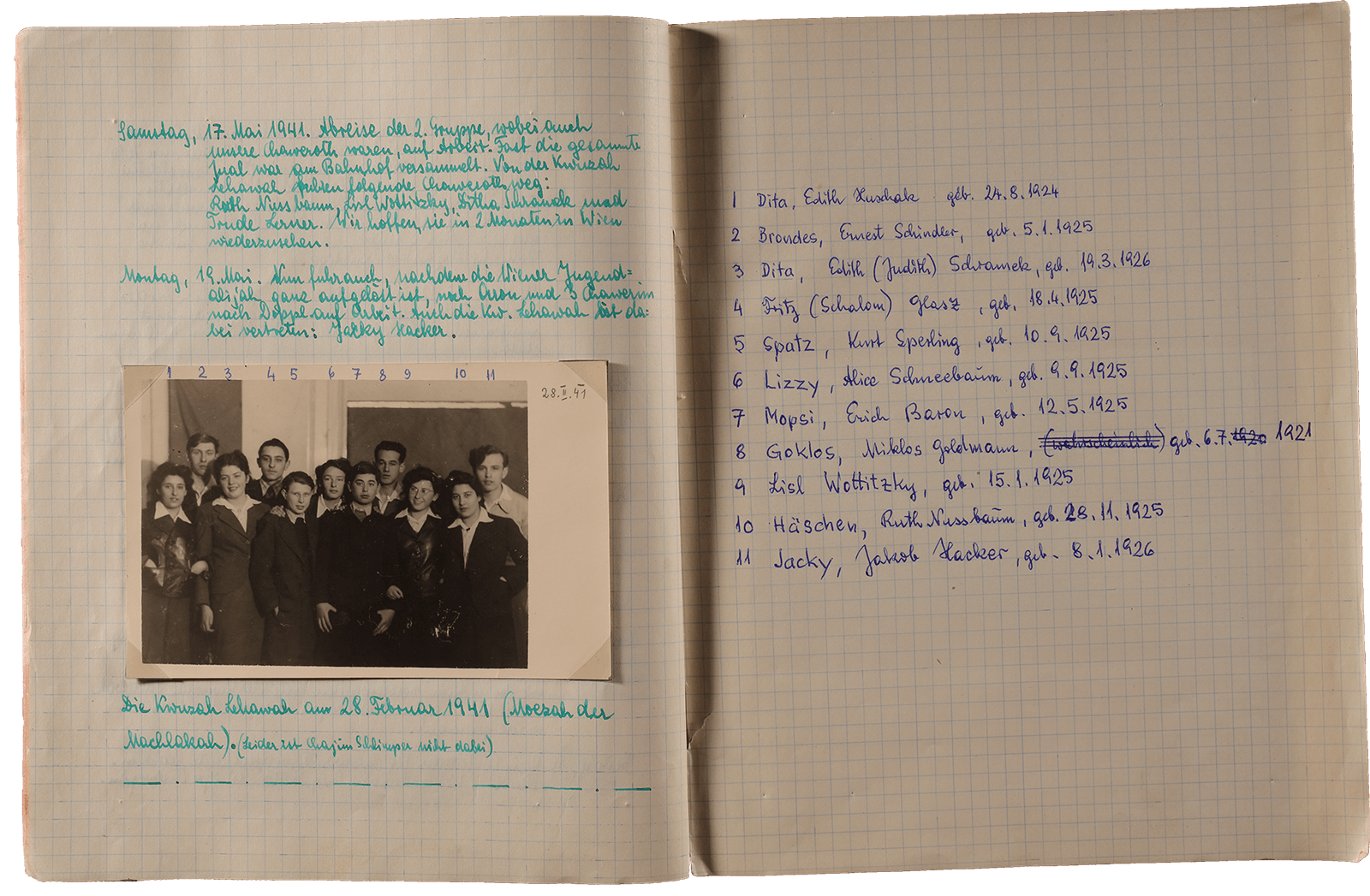

People who did not conform to the system risked persecution themselves. Some decided to put up resistance despite the danger it posed to their lives. Their actions ranged from helping persecuted individuals and distributing anti-Nazi propaganda to putting up armed resistance. There were many fatalities, especially among the members of the Communist resistance. The Socialist resistance also suffered many fatal casualties. Following the defeat of the German Wehrmacht at Stalingrad in 1943, some sections of the war-weary and disillusioned population began question the certainty of a German victory. This being so, the resistance movement against the Nazi regime also proliferated in the final months of the war.

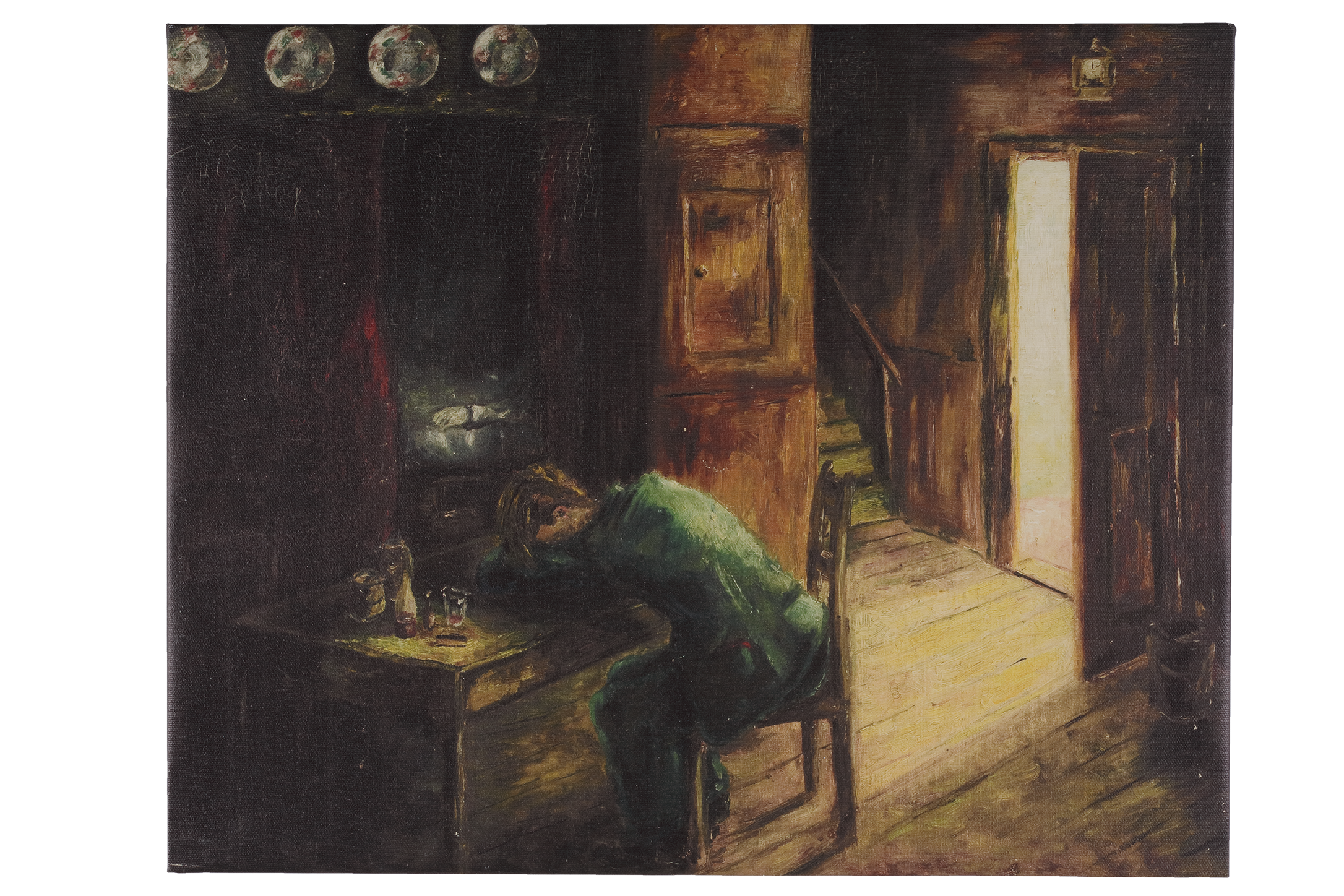

Those persecuted by the Nazi regime were increasingly marginalised and their possible courses of action diminished as time went on. While, at first, escape was still legally an option for many Jews – subject to the extorted surrender of their assets – with the outbreak of war it became impossible. The only options were to attempt to leave the country illegally or go into hiding as an “U-boat”. Some chose suicide as a last resort.

Following the occupation of Belgium, the Netherlands and France by the German Wehrmacht, Jews and other victims of political persecution who had fled there from Austria were under threat once more. Many were subsequently interned in interim camps such as Drancy, Gurs or Westerbork and deported from there to the concentration and extermination camps in the German Reich. Only a few managed to escape and continue their flight or survive in hiding.

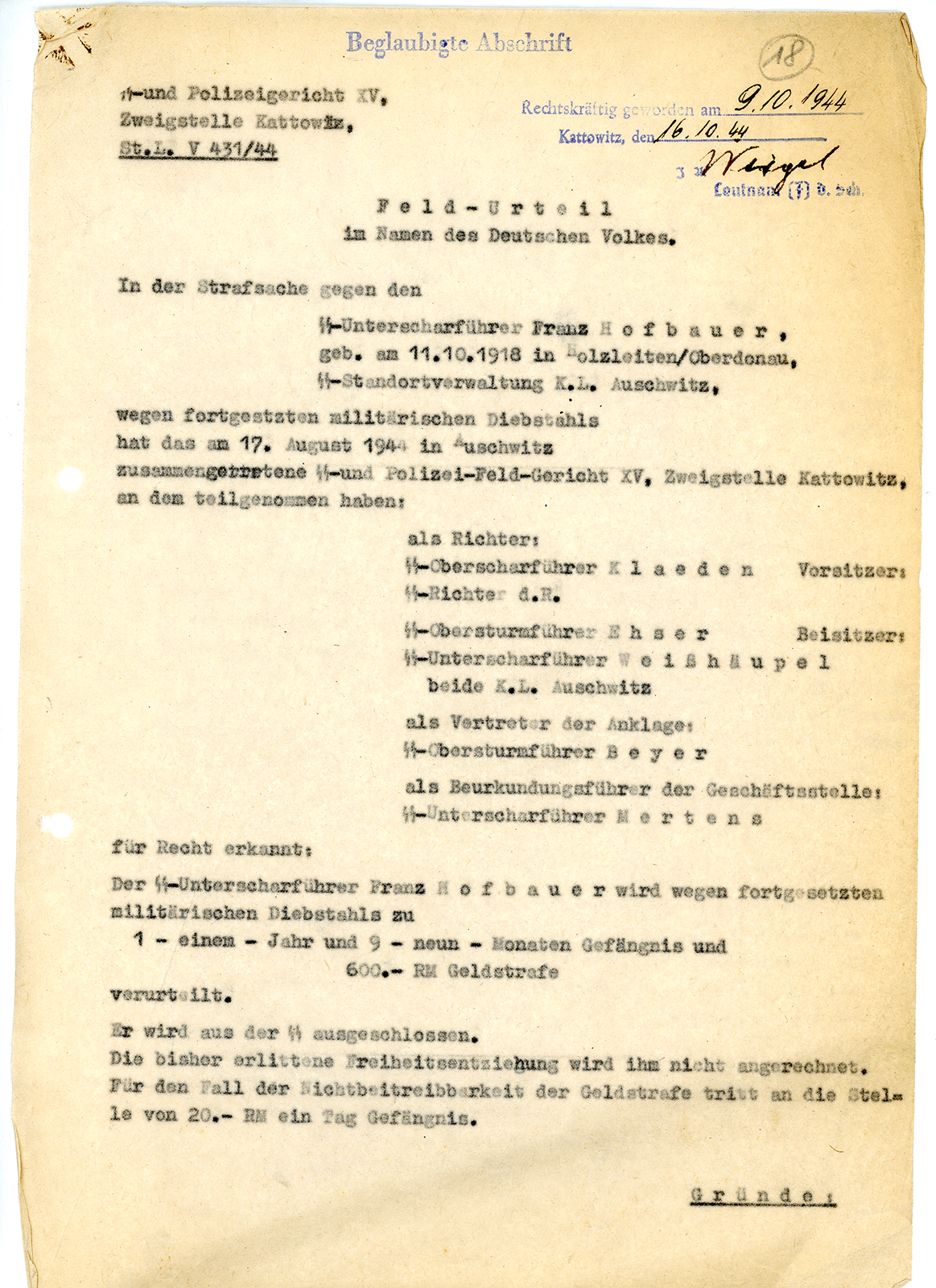

The hierarchical system at Auschwitz not only assigned certain areas of responsibility and tasks to the camp staff, but also allowed individual staff members to act with relative autonomy. Many took advantage of their positions of power to torture, punish or even kill prisoners but, above all, they did so to enrich themselves personally. Prosecutions were rare.

The prisoners of Auschwitz, on the other hand, had virtually no chance stopping their dehumanisation or preserving their identity. Even though different courses of action were available to prisoners depending on their position in the camp hierarchy, life in the camp meant a permanent fight for survival for all of them. Nevertheless, some managed to organise themselves, with Polish and Austrian prisoners founding an international resistance group in the camp.

From the camp administration downwards, everyone who worked at Auschwitz was involved in the machinery of murder there to varying degrees. Not only those who sat at the controls, such as the Head of the Political Department, Maximilian Grabner from Vienna, or the Upper Austrian Head Guard of the women’s camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, Maria Mandl, decided who among the prisoners would live and who would die. The entire camp staff was permitted to torture prisoners at will, punish them, murder them or arrange for them to be killed. They were more or less free to treat the inmates as they pleased. The extent to which they were individually guilty of perpetrating crimes for the most part depended on their personal belief systems and dedication. Even the large-scale theft of the deportees’ looted belongings rarely had consequences for the perpetrators. Just a tiny minority chose to protect or help the inmates.

The camp staff's daily routine also included recreation and entertainment; there were organised excursions and a cultural programme. Ensemble members from various Austrian cultural institutions such as the Burgtheater even travelled to Auschwitz for this purpose.

The kapos appointed by the camp administration acted as intermediaries between the prisoners and the camp staff, between victims and perpetrators. Although they were prisoners themselves, the kapos were functionaries: they not only had to help the camp staff oversee and punish the prisoners; at the same time, they had much more autonomy than their fellow prisoners. They were mostly political prisoners or so-called criminals, whose living conditions were superior to those of the Jewish prisoners or those classified as “gypsies”. Because of their position in the camp hierarchy, not to mention their connections to the SS, kapos were also in a position to save prisoners’ lives, such as the Viennese Hans Schorr, who was able to intervene on the ramp to save Norbert Lopper’s mother from the gas chamber. Other kapos, however, took advantage of their position – even to the point of committing sexual assault against other prisoners, or murder. Although kapos could themselves become perpetrators, they were nevertheless also victims who, like everyone else, had to fight against dehumanisation in the camp.

One possible course of action, especially for political prisoners, was to become organised: Heinrich Dürmayer from Vienna, camp elder at the Auschwitz main camp from September 1944 to January 1945, and Hermann Langbein, who worked in the prisoners’ record office, were just two of the Austrian political prisoners who were active in the camp resistance. They founded the international “Auschwitz Combat Group” in association with the Polish camp resistance and were in contact with resistance organisations in Poland and Austria. The group organised escapes and transmitted information about the extermination camp to the outside world in the hope it would incite the Allies to intervene. Above all, the resistance movement provided a sense of solidarity and mutual aid among its members and was one way of counteracting the inhumanity of Auschwitz.

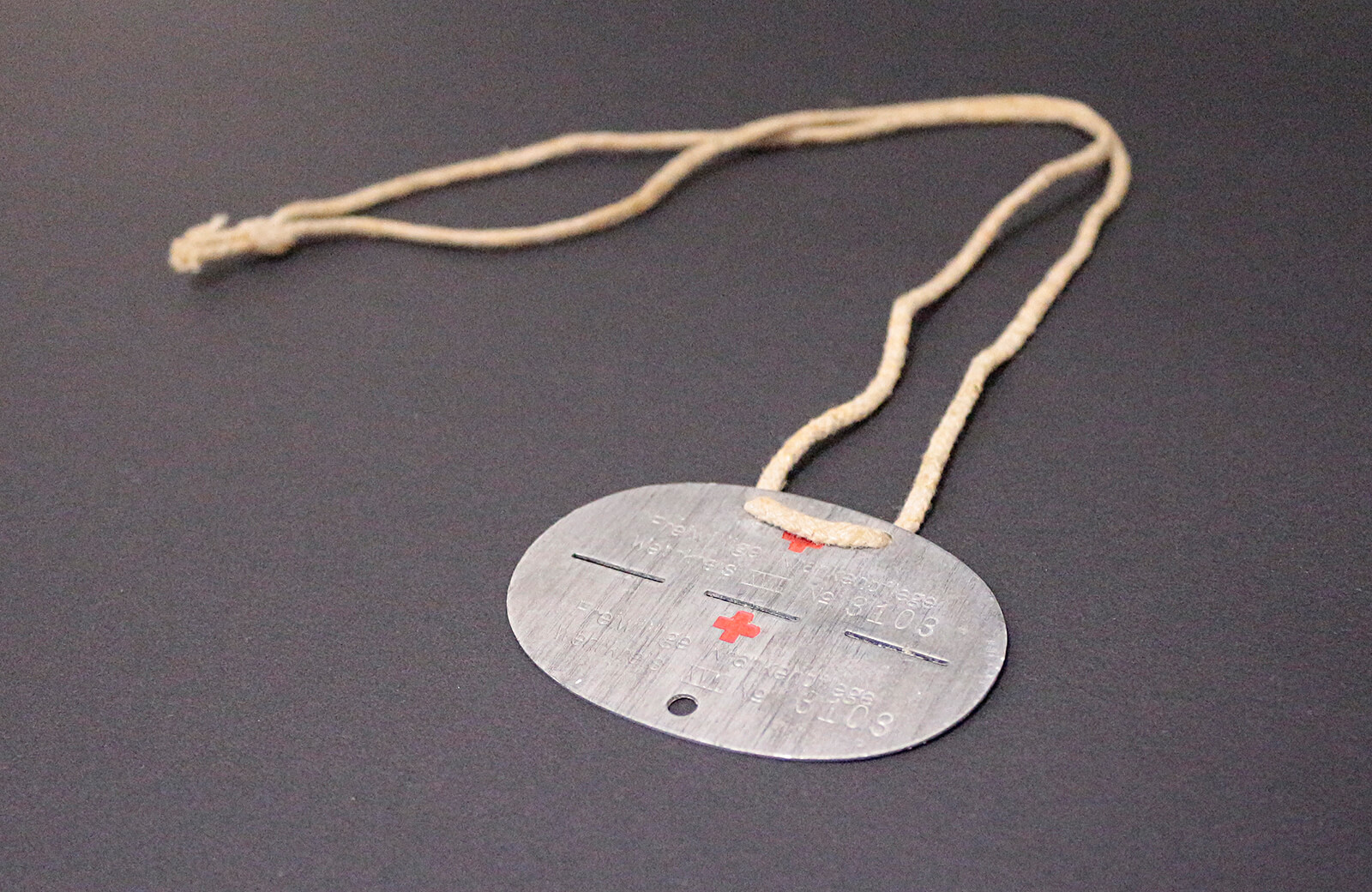

In contrast, the Jewish prisoners and Roma and Sinti had far fewer options. A few managed to smuggle a keepsake from their former life into the camp with them, others were kept alive by love and friendship, for example, by religion, or even the determination to be able to bear witness to the atrocities later on.

The different conditions in the separate parts of the camp essentially determined the options available to those imprisoned there. Those who did not manage to secure a privileged position, such as in the record office, or who did not have an education that enabled them to be of use to the camp SS; those who did not have connections to other prisoners or to the guards, or those who were simply less fortunate were barely able to survive the inhumane conditions in Auschwitz.

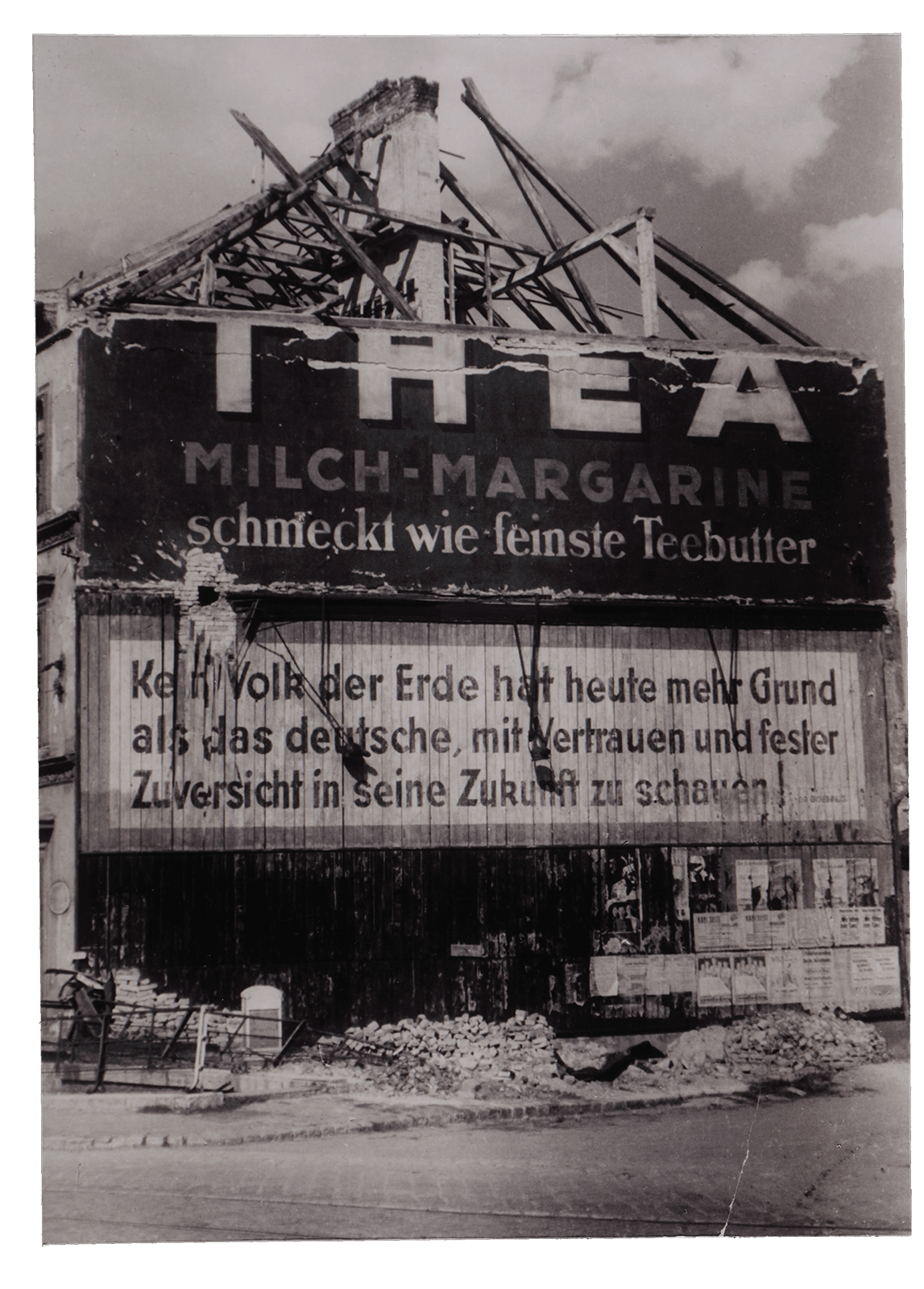

The defeat of the German Wehrmacht at the Battle of Stalingrad in the winter of 1942/43 marked a turning point in World War II. Hereinafter, the military successes of the Allies began to accumulate, and the war’s battlegrounds began to edge closer to the former Austrian territory. In the cities especially, food and heating material were in increasingly short supply. The Volkssturm (“People’s Storm”) and the Hitler Youth became the last line of defence mobilised by the Nazi Party to fight the war.

With the Red Army on the advance, the SS dissolved the camps in the East and evacuated the prisoners. Many of them were sent to Mauthausen concentration camp or one of its numerous subcamps. In addition, vast numbers of prisoners and Jewish slave labourers were driven through Austria on death marches. Right up until the end of the war, atrocities and massacres were perpetrated in many places as the civil population looked on, or sometimes even participated. Civilians only provided help and assistance in isolated cases.

In May 1945, the Allies had taken control of the entire Austrian territory.

After the defeat at Stalingrad in the winter of 1942/43, the military successes of the Allies started to mount up. From August 1943, the Allied Air Force also carried out air raids on targets in Austria. In November of the same year, the Foreign Ministers of the Soviet Union, Great Britain and the USA adopted the Moscow Declaration, which declared the “Anschluss” of Austria to the German Reich “null and void”.

With the German Reich rapidly running out of provisions, the Nazi regime declared “Total War”. The Volkssturm from October 1944 and then the Hitler Youth were mobilised as the last line of defence. The poorly-equipped and inadequately trained elderly, adolescents and children were expected to demonstrate a fanatical readiness for combat.

Upon the retreat of the German Wehrmacht, the camps in the East were "evacuated" and dissolved, and the remaining prisoners were forced to join “death marches” heading westward, also through Austria. For many, the destination was Mauthausen concentration camp or one of its numerous subcamps. On one death march to Mauthausen, SS men murdered 228 Hungarian Jews at the reception camp in Hofamt Priel near Persenbeug in Lower Austria on the night of 2 to 3 May 1945. Right up until the end of the war atrocities and massacres were also perpetrated at many other locations as the civil population looked on, or sometimes even participated. Civilians only provided help and assistance in isolated cases, sometimes to avoid risking punishment.

While the Red Army crossed the Hungarian-Austrian border in March 1945 and fought its way towards Vienna, the American and British Allies were taking control of the western provinces. From 5 to 8 May 1945 the US Army liberated Mauthausen concentration camp and its remaining subcamps. On 8 May, the German Wehrmacht capitulated.

Part of the Austrian population perceived the collapse of the Nazi regime as a defeat and an occupation. For others, the capitulation meant liberation from Nazi tyranny. While the battles for Vienna were still raging, the Socialist and Communist Parties were re-established, and the Austrian People’s Party took the place of the former Christian Social Party. All parties signed the Declaration of Independence of the Republic of Austria on 27 April 1945. On the same day, the first Provisional State Government was constituted under the control of the Allied Military Administration.

In autumn 1944, the transport of prisoners from Auschwitz to the concentration camps in the inner parts of the German Reich territory commenced. Despite this, the mass killings at Auschwitz continued.

At the same time, the SS did everything in its power to eliminate all traces of the genocide by setting alight the administrative files and destroying the gas chambers, detonating the extermination facilities and burning the written documents that evidenced the atrocities committed at Auschwitz. In an attempt to thwart these efforts, remaining inmates collected and secured evidence of the crimes committed there. On 27 January 1945 Auschwitz was liberated by the Red Army. At that time, around 35 Austrian inmates were still in the camp.

Despite the imminent collapse of the Nazi regime, the killings continued at Auschwitz. Trains carrying deportees continued to arrive, for the most part their occupants were killed immediately. On 5 October 1944, the last direct transport left Vienna for Auschwitz carrying 100 Jews. Some elements of the extermination facilities at Auschwitz had already been dismantled, with the plan to get them up and running elsewhere. At the same time, the prisoners who remained in the camp were forced to go on so-called death marches to the concentration camps further inside the German Reich. Many of them were killed by their guards or died of exhaustion, either en route or upon arriving in other concentration camps.

In the final phase of the war, the SS also did everything in its power to eliminate all traces of the genocide at Auschwitz: the extermination facilities at Auschwitz-Birkenau were detonated, and the majority of the written documentation was incinerated or taken away. To prevent them from succeeding, prisoners secured evidence of the atrocities committed there. The Viennese doctor Otto Wolken, for example, concealed his clandestine records of selections and death rates. He hid in the Auschwitz camp area until the SS had withdrawn and then he took care of sick prisoners.

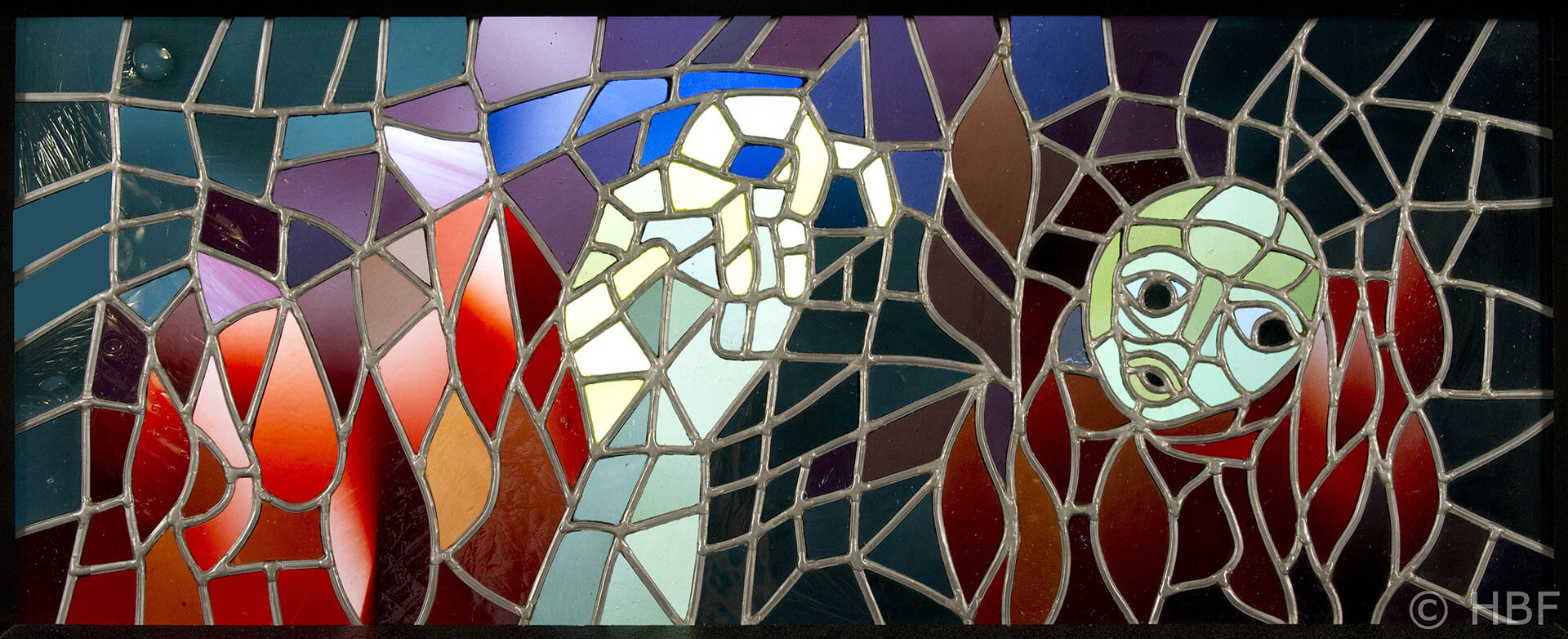

On 27 January 1945 Auschwitz was liberated by the Red Army. Around 35 Austrian prisoners were still in the camp at that time. Some political prisoners, among them Franz Danimann and Kurt Hacker, set up an “Austrian block” in Block 8 of the main camp and Heinrich Sussmann painted a large flag in Austria’s red-white-red on its inside wall. All remaining prisoners were cared for by the Red Army and the Red Cross, which had arrived shortly afterwards, and preparations were made for them to be repatriated to their home countries. Leftover materials from the camp, clothing, wood and building materials were distributed to needy Poles, and by summer 1947 the camp itself had already been declared a memorial site.

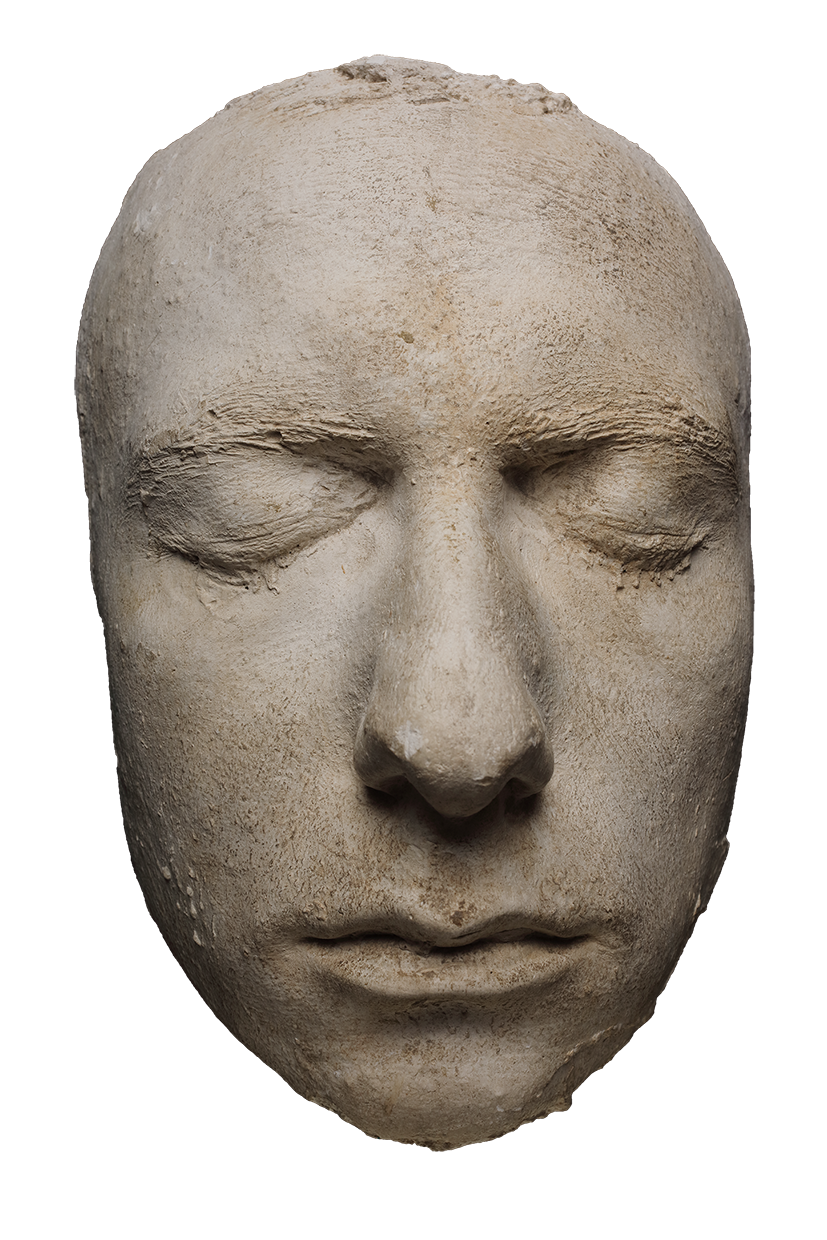

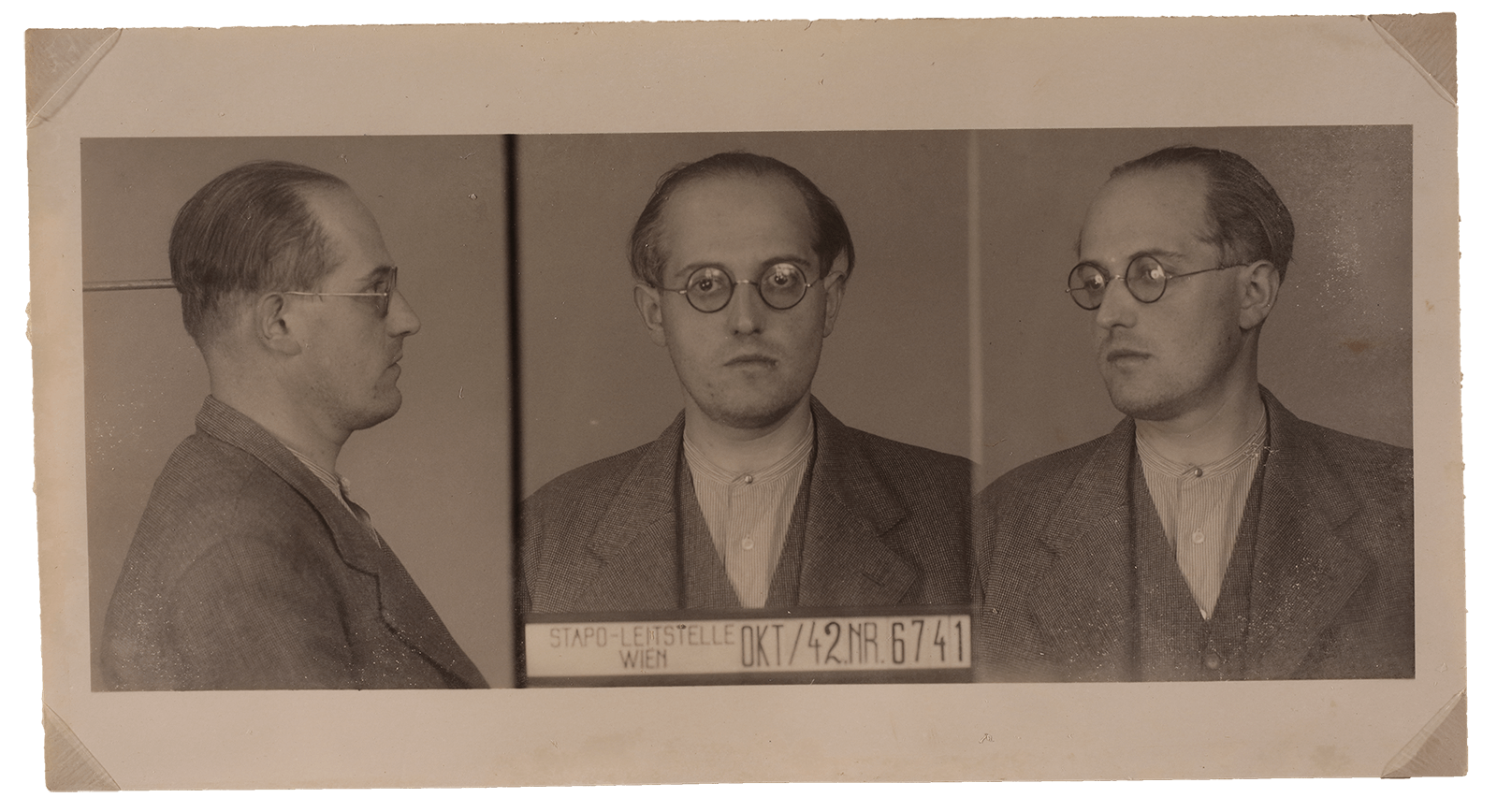

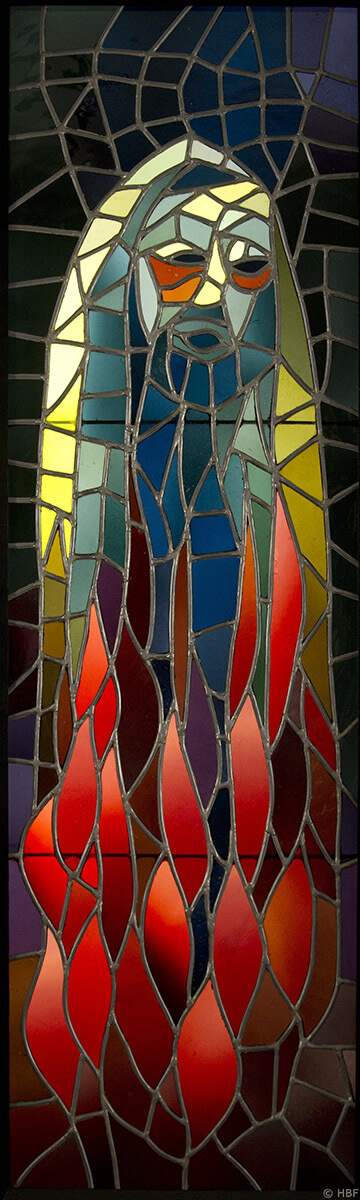

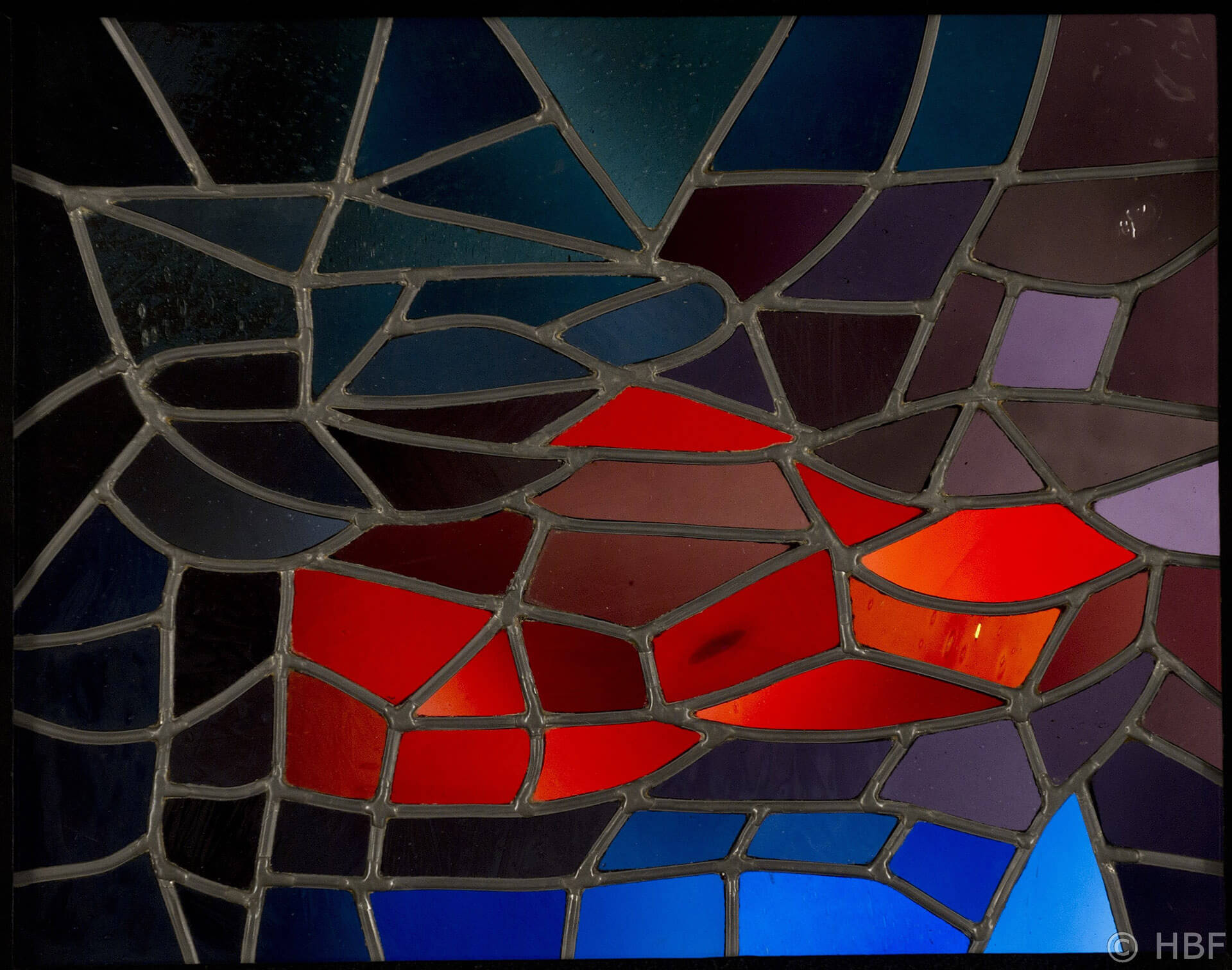

Glass windows created for the 1978 Austrian exhibition at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial, designed by Heinrich Sussmann

“The idea behind the glass windows was actually to portray those people who had been maltreated, dismembered, cremated, pulled apart to remove gold teeth (…) as whole once more. Not dismembered. Not pieces of flesh, but as the whole, intact beings that they had once been.”

Heinrich Sussmann in a 1985 interview

National Fund of the Republic of Austria for Victims of National Socialism

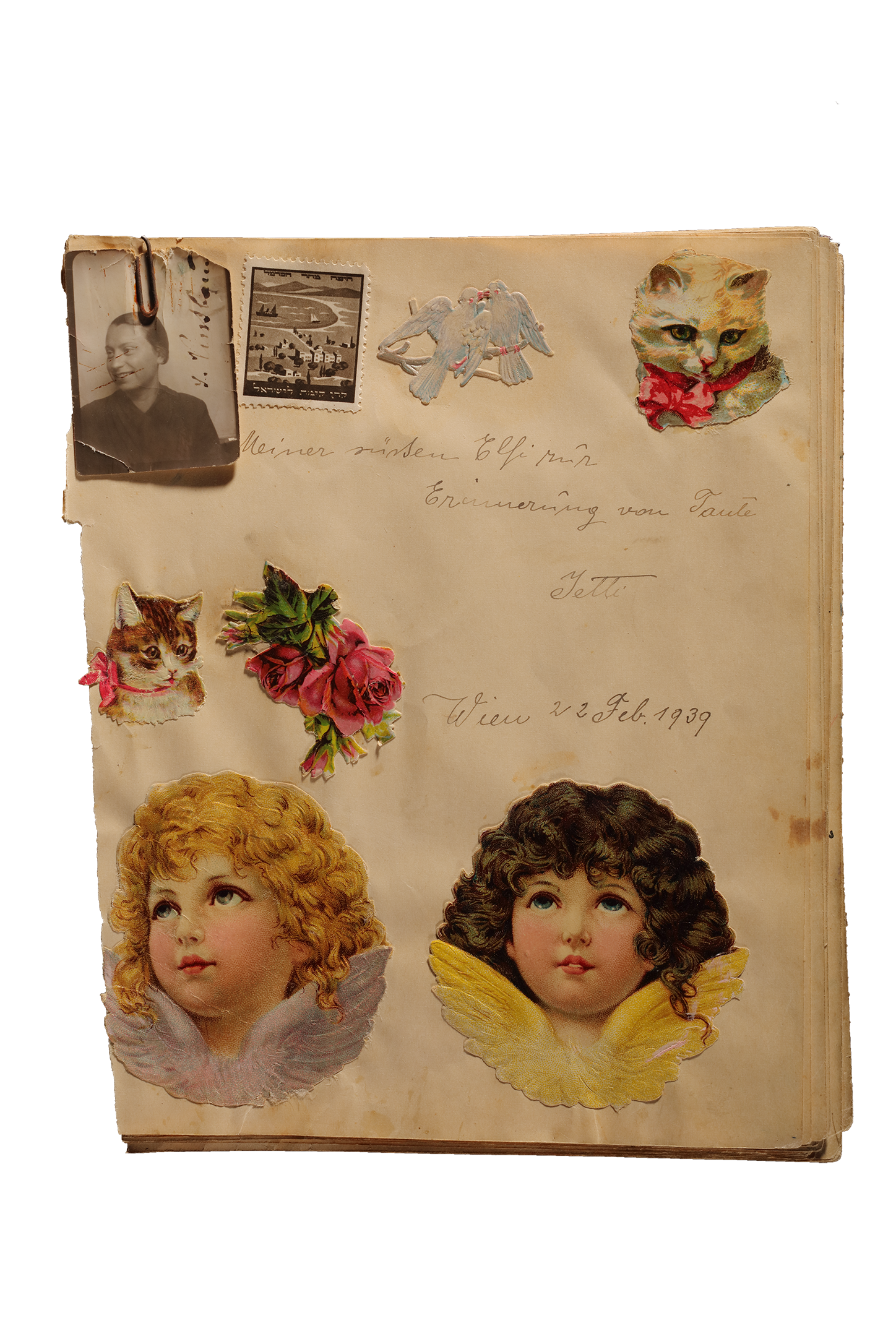

Heinrich and Anna Sussmann were persecuted for being Jewish. They married in Paris in 1937 and joined the Communist Resistance there. In June 1944 the pair was captured by the Gestapo and deported to Auschwitz. Anna Sussman had been in the late stages of pregnancy at the time; she gave birth to a son in the woman’s camp. He was murdered at birth. In the interviews, the couple recounts their sufferings in the concentration camp.

Interview with Heinrich (1904 – 1986) and Anna Sussmann (1909 – 1985)

Interview material (audio) by Hugo Portisch, 1983

Archive of the Austrian Broadcasting Corporation, Vienna

Interview with Heinrich Sussmann

Interview with Anna Sussmann