Walter Fantl-Brumlik

(Bischofstetten 1924 – Vienna 2019): Forced labour at the Gleiwitz I satellite camp

“As long as I had the belt, I could survive”

-

Walter Fantl-Brumlik and his sister Gertrude with their parents, ca. 1930 -

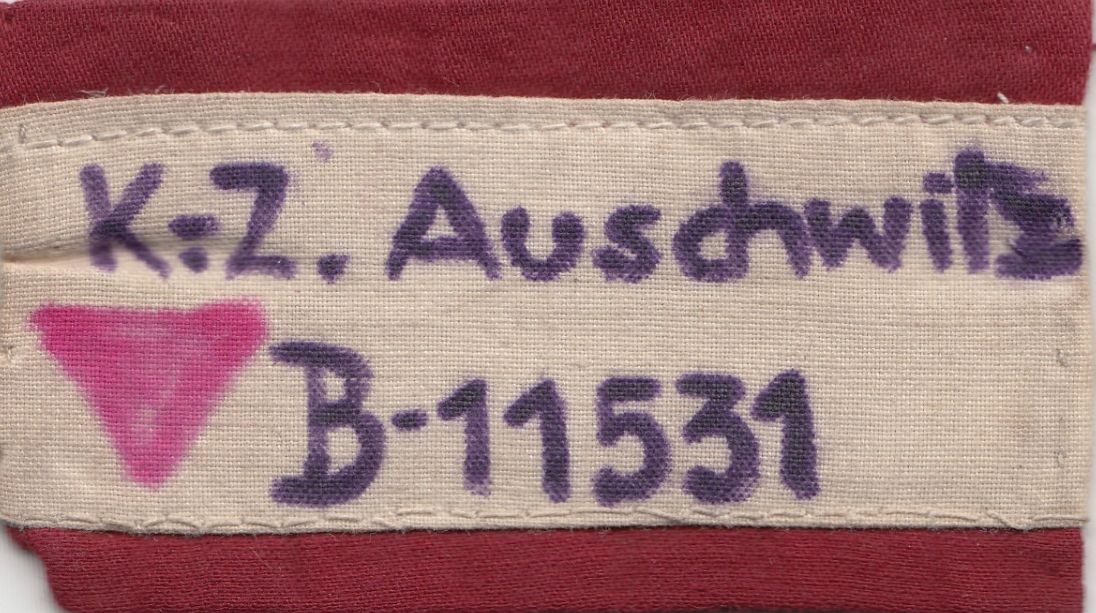

Patch for Walter Fantl-Brumlik’s clothing so that he would be recognised as a concentration camp survivor by the Russian soldiers -

Walter Fantl-Brumlik‘s belt, his “survival object” -

Film clip with Walter Fantl-Brumlik showing his belt

Bischofstetten, where Walter Fantl-Brumlik grew up, is situated not far away from St. Pölten. His mother Hilda and father Arthur ran a general store there. Walter Fantl-Brumlik says he has no recollection of any antisemitism until Austrofascism arrived. His was the only Jewish family living in the small town, where they lived religiously as best they could. After finishing primary school, Walter went on to attend secondary school in St. Pölten, where he was also confirmed.

When the Nazis came to power, the family was shocked to discover that many of their friends had been illegal Nazis. The more educated illegal Nazi Party members had not behaved “improperly” towards them. The “primitive” among them were different; they immediately put up a sign on the shop saying “Do not buy from Jews”. The two rival shops joined in with the anti-Jewish boycott. Walter was “subjected to verbal abuse by a few youths, that is, by our competitors. But we had a dog... it was trained and when I went out on the street with it, none of these youths who wanted to accost me came too close.”

Attempts to flee to the USA failed due to bureaucratic hurdles. Following the November pogrom in 1938, the business was closed down, his father was temporarily arrested, and the house with the business premises was expropriated. The family of four was forced to move to Vienna. After retraining as a locksmith and precision mechanic, Walter Fantl-Brumlik worked in the technical department of the Jewish Community in Vienna. In October 1942, the family was deported to Theresienstadt concentration camp. His parents and sister shared living quarters, Walter was put up in the home for adolescents, only later were the family accommodated together. He worked as a locksmith and, later on, in the kitchen. After two years, Walter and his father were transported to the “East”. Unlike the deportation to Theresienstadt, this time the deportees were transported in cattle cars. A nightmare began that would stay with Walter Fantl-Brumlik forever. After reaching Auschwitz-Birkenau, arrivals were subjected to the “selection”, his father was sent to one side, Walter to the other. He tried to go with his father, but it was not permitted. The doctor carrying out the selection had deemed his father unfit to work and he was subsequently murdered in one of the gas chambers. Walter Fantl-Brumlik was assigned a number. He was sent to Gleiwitz I, one of Auschwitz’s many subcamps, where he had to work shifts performing forced labour for the German Reichsbahn. At that time, he was still convinced that his mother and sister could survive in Theresienstadt. Only after the war was over did he learn that they had both been deported to Auschwitz nine days after him and that his mother had been murdered immediately upon arrival. His sister succumbed to typhus at Bergen-Belsen concentration camp just days before it was liberated.

One of Walter Fantl-Brumlik’s survival strategies was to keep a belt that he had taken with him – it became his survival object: “I usually wore the belt so that no one could take it from me. I also had it on at night, but not on the last hole so that I could still breathe, because otherwise the belt would have been gone. For me, the belt is a memento from the concentration camp. I don't know where I got it, but I couldn’t part with it. My thought was ... as long as I had the belt, I was still alive. I would have got a lot of bread for it, it was a horrendous thing to get bread in the camp, in Auschwitz. I thought that if I lost the belt, I would also lose my life. That may sound superstitious, but at that time it gave me strength.”

In the end, Walter Fantl-Brumlik was so weak that he would barely have survived the death march in the course of the evacuation of the concentration camps without the help of other inmates. The liberation by the Red Army was his last-minute salvation. He later searched Theresienstadt in vain for his mother and sister and following an eventful journey arrived in Vienna. While other survivors emigrated to Palestine or America, Walter Fantl-Brumlik initially wanted to stay in Austria, also because he was not willing to simply accept the expropriation of the family property.

Literature

Johannes Kammerstätter, Heimat zum Mitnehmen. Unsere jüdischen Landsleute und ihr tragbares Vaterland, vol. 2, Wieselburg 2012, p. 80–87.

Gerhard Zeilinger, Überleben. Der Gürtel des Walter Fantl, Vienna 2018.

Dokumentarfilm Walter Fantl-Brumlik, Der Lebensgürtel, 5 min., Salzburg-Vienna 2017 (unitv.org).