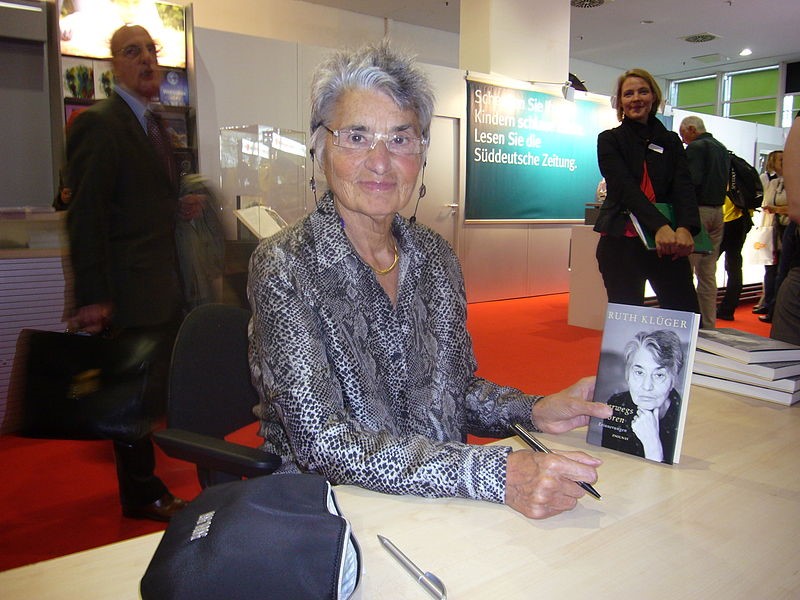

Ruth Klüger

(Vienna 1931 – Irvine, California 2020): Being an adolescent at Auschwitz

The art of survival

Ruth Klüger was a renowned German scholar who worked at several American and European universities. When she wrote down her recollections of her childhood and early adolescent years, she had no idea that they would become a bestseller and be translated into several languages. After all, the book “weiter leben” (published in English under the title “Still Alive”), first released in 1992, is not an easy read; it is challenging in literary terms and describes her experiences in numerous concentration camps, including the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. In 2008, her memoirs were selected for the campaign Eine Stadt. Ein Buch (“One city. One book”) and the City of Vienna distributed 100,000 free copies.

Ruth Klüger's father, Viktor Klüger (1899–1944), was a gynaecologist in Vienna. After the “Anschluss” he was arrested; he fled to Italy in the summer of 1938 and then later to southern France. His wife and daughter had to stay behind because the family could not afford the Reich Flight Tax imposed on those leaving the country. His escape proved futile: Viktor Klüger was arrested in April 1944 and deported from Drancy collection camp to the Baltic States in May 1944, where he was murdered.

In September 1942, Ruth Klüger and her mother Alma were deported from Vienna to Theresienstadt and on 16 May 1944 they were transferred from there to Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp, where they were interned in the so-called Theresienstadt family camp. In her memoirs, she debates the fact that the wagons used in these deportations were often described as cattle wagons, but they were actually freight cars. If animals had been transported in this way, it would have been deemed animal cruelty. She refutes the image often portrayed in films of a “hero” holding a child gasping for air to the hatch in the wagon. Those who stood by the hatch used their elbows and did not surrender their position. The wagon reeked of urine and faeces. An elderly woman lost her composure, sat on Ruth’s mother’s lap and urinated. Her mother pushed the old woman away, overcome with anger and indignation. Following their arrival at Auschwitz her mother suggested that they go together to the electrically charged barbed wire and take their own lives. That went beyond the comprehension of a twelve-year-old. In the days that followed came the hunger, the thirst, the smoke of the crematoria, stench, boredom, brutality, overcrowding, helplessness, corpses, bouts of anxiety.

Fantasies were a comfort to Ruth Klüger; she wanted to document everything in a book one day and began to write poetry. She memorised the poems because she had nothing to write with. It was not until 1945 that she wrote down the poetry, such as this verse from the poem “Auschwitz”:

God, you alone may give,

the great, sacred human life,

You give existence and you give death.

And you, you see this endless killing,

you see the bloody, savage hordes,

and people scorn your highest commandment.

Casting the trauma into verse and regularity was for her a counterbalance to the chaos, a therapeutic attempt to counter the senselessly destructive.

In June 1944 her life was saved by a stroke of luck. Women were wanted for work and they had to line up naked in two rows in a barrack. Then, two SS men decided who they thought was fit to work and who was not. Her mother was deemed fit to work, Ruth was rejected as too young. Outside the barrack, her mother tried to persuade her to sneak past the guard, join the queue again and claim she was 15 years old. The daughter felt unable to lie like that; she would say was that she was 13 at most. She actually managed to sneak into the barracks and queue up in the other line. Next to the SS officer, who was in good spirits, sat a young female inmate who was taking down his decisions. The inmate got up, went up to her and asked how old she was: “Thirteen.” Insistently the woman urged her, “Say you are fifteen.” The female inmate helped her again as she stood in front of the undecided SS officer. Ruth had muscles in her legs and could work, she declared. So Ruth Klüger was put on the list of those fit to work and was deported with her mother to the next concentration camp, Christianstadt, a subcamp of the Groß-Rosen concentration camp. The Theresienstadt family camp was dissolved in early July 1944. Those who were fit to work were selected, the rest were murdered.

Literature

Ruth Klüger, weiter leben. Eine Jugend, Göttingen 1992.

Ruth Klüger, unterwegs verloren. Erinnerungen, Vienna 2008.

Ruth Klüger, Zerreißproben. Kommentierte Gedichte, Munich 2016.

Renata Schmidtkunz, Das Weiterleben der Ruth Klüger, documentary, 2013.