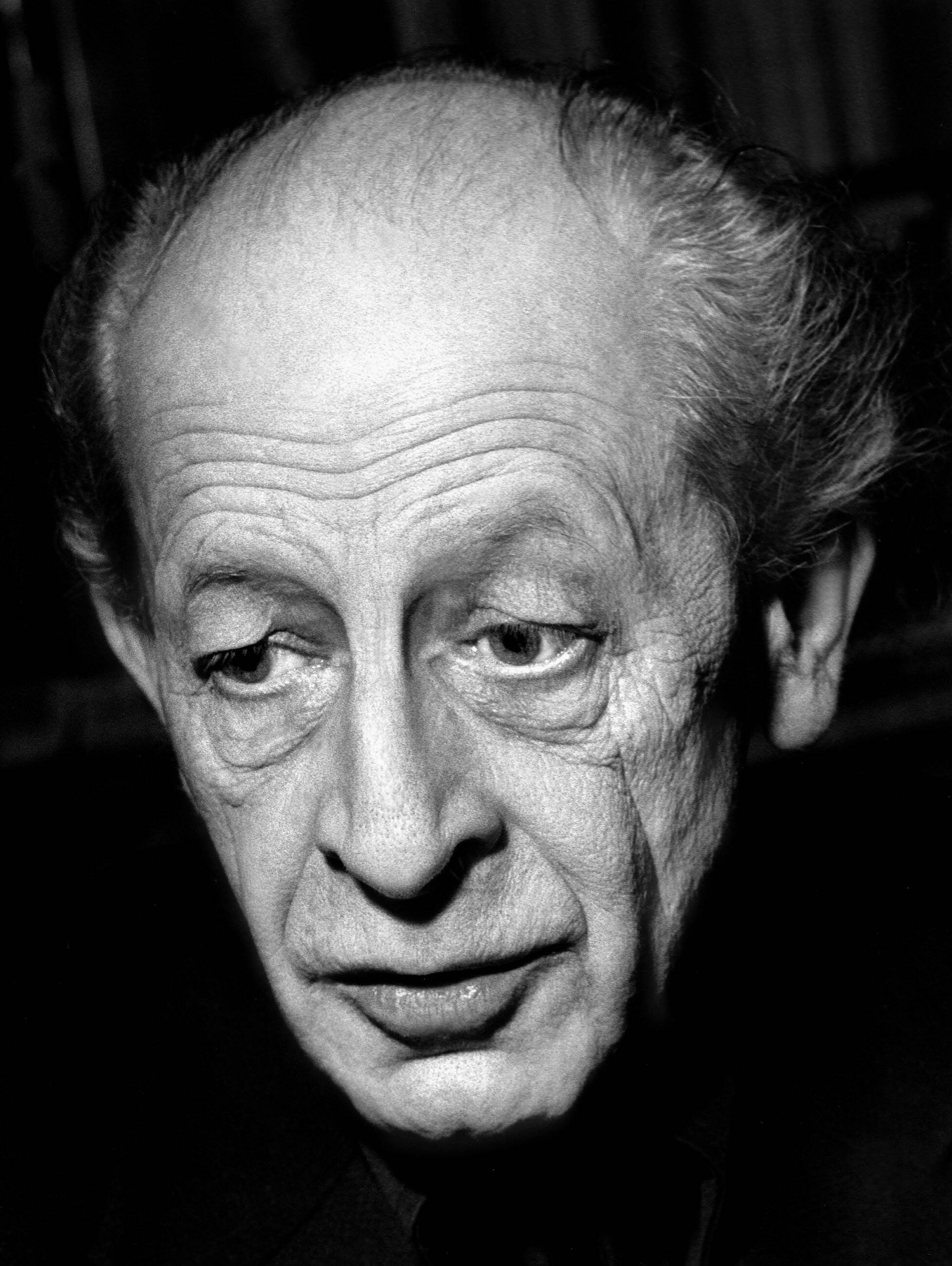

Jean Améry (Hans Mayer)

(Wien 1912 – Salzburg 1978): “As far as language goes”.

The literary legacy of an Auschwitz survivor

Jean Améry was born Hans Mayer in Vienna on 31 October 1912, into an assimilated Jewish family that considered itself more Austrian than Jewish: his father came from a traditional Jewish family in Hohenems, his mother’s family had converted to the Catholic faith. After a few years in Hohenems, Améry, whose father had fallen in the First World War, spent his youth with his mother in a Catholic environment in the Salzkammergut region and in Vienna. He had dreamed of becoming a writer since his schooldays, and went on to complete an apprenticeship as a bookseller in Vienna, where he also studied and attended lectures on literature and philosophy. He also published the literary magazine Die Brücke and wrote his first novel Die Schiffbrüchigen in 1934/35.

Améry was an opponent of Hitler’s regime in Germany from the outset, but it was only after the “Anschluss” of Austria to the German Reich and the ensuing persecution by the Nazis that he became aware of his other, Jewish identity, which the Nazis had conferred upon him through the Nuremberg Laws. “When the thunderclap came on 11 March 1938, when my country exulted and threw its arms around the neck of the Führer of the Greater German Reich, I was prepared.” Immediately after the “Anschluss”, Améry and his wife Regine fled to Belgium. In 1940 he was arrested in Antwerp as an “enemy alien” and deported to Camp Gurs in southern France. A year later, he managed to escape from the camp. He fled back to Belgium, where he went into hiding and joined the Belgian resistance movement.

“My Auschwitz number is shorter than the Pentateuch or the Talmud but provides much more thorough information.”

On 23 July 1943, he was caught distributing anti-Nazi propaganda leaflets and arrested. He was interrogated and tortured for several days at Fort Breendonk. Finally, on 15 January 1944, he was deported to Auschwitz via the Malines (Mechelen) assembly camp and transferred to Auschwitz III-Monowitz where he was given the prisoner number 172364 and sent to perform forced labour in the Buna factories. From June of the same year, he worked in the typing pool at the Buna works. When Auschwitz concentration camp was evacuated, Améry was first taken via Gleiwitz II to Mittelbau-Dora, a subcamp of Buchenwald concentration camp, and then to Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated by the British army in April 1945. “Back in the world with a live weight of forty-five kilograms and a zebra suit.”

When the war was over, Améry lived in Brussels where he worked as a cultural journalist and writer and was initially published in various German-language Swiss newspapers. He categorically rejected the publication of his work in Germany. From the 1950s onwards, he began to use the anagram of Mayer, “Améry” and eventually abandoned his German name. It was the first Frankfurt Auschwitz trial in 1963 that finally provided him with the necessary impetus to deal with his survival in literary form. In 1966 he published the essay collection Jenseits von Schuld und Sühne. Bewältigungsversuche eines Überwältigten (“At the Mind’s Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor of Auschwitz and Its Realities.”), in which he reflected on his exile, torture and concentration camp experiences as well as his identity as a Jewish victim. The volume, although initially rejected by renowned publishers, made him famous overnight and became a central text of German-language Holocaust literature.

“The ordeal, the most terrible event that a human being can keep within himself (...). Whoever was tortured, stays tortured. Whoever succumbed to torture can no longer feel at home in the world. The trust in the world, which was already partly collapsed with the first blow, but to the full extent finally in the ordeal, is not regained.”

Améry, as he himself professed, was no longer able to feel at home in the world. In addition to many reading tours through Germany and radio and television appearances, he continued to publish, but his reception by the public remained limited to his victim status. Finally, in 1976, he published the essay Hand an sich legen. Discourse über den Freitod (“On Suicide: A Discourse on Voluntary Death”) in which he advocated so-called rational suicide, i.e. the more or less rationally justified suicide. “The inclination to suicide is not a disease that can be cured, like the measles. (...) Suicide is a privilege of the humane.” On 17 October 1978, Jean Améry took his own life in the Hotel Österreichischer Hof in Salzburg. He is buried at the Vienna Central Cemetery in a grave of honour (group 40, no. 132).

Literature and sources

Jean Améry , Jenseits von Schuld und Sühne. Bewältigungsversuche eines Überwältigten. Essays, Munich 1966.

Jean Améry, Hand an sich legen. Diskurs über den Freitod, Stuttgart 142012.

Interview: Zeugen des Jahrhunderts – Jean Améry (ZDF, 1978); online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lvtAvs-4JBs

Der Grenzgänger. Jean Améry im Gespräch mit Ingo Hermann, Göttingen 1992.

Wilfried F. Schoeller, Gegen sich denken können. Zum 90. Geburtstag von Jean Amery. In: Deutschlandfunk, 3.11.2002; online: https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/gegen-sich-denken-koennen-zum-90-geburtstag-von-jean-amery-100.html

Lukas Brandl, Philosophie nach Auschwitz: Jean Amérys Verteidigung des Subjekts, Vienna/Berlin 2018.

Irene Heidelberger-Leonard, Jean Améry. Revolte in der Resignation, Stuttgart 2004.