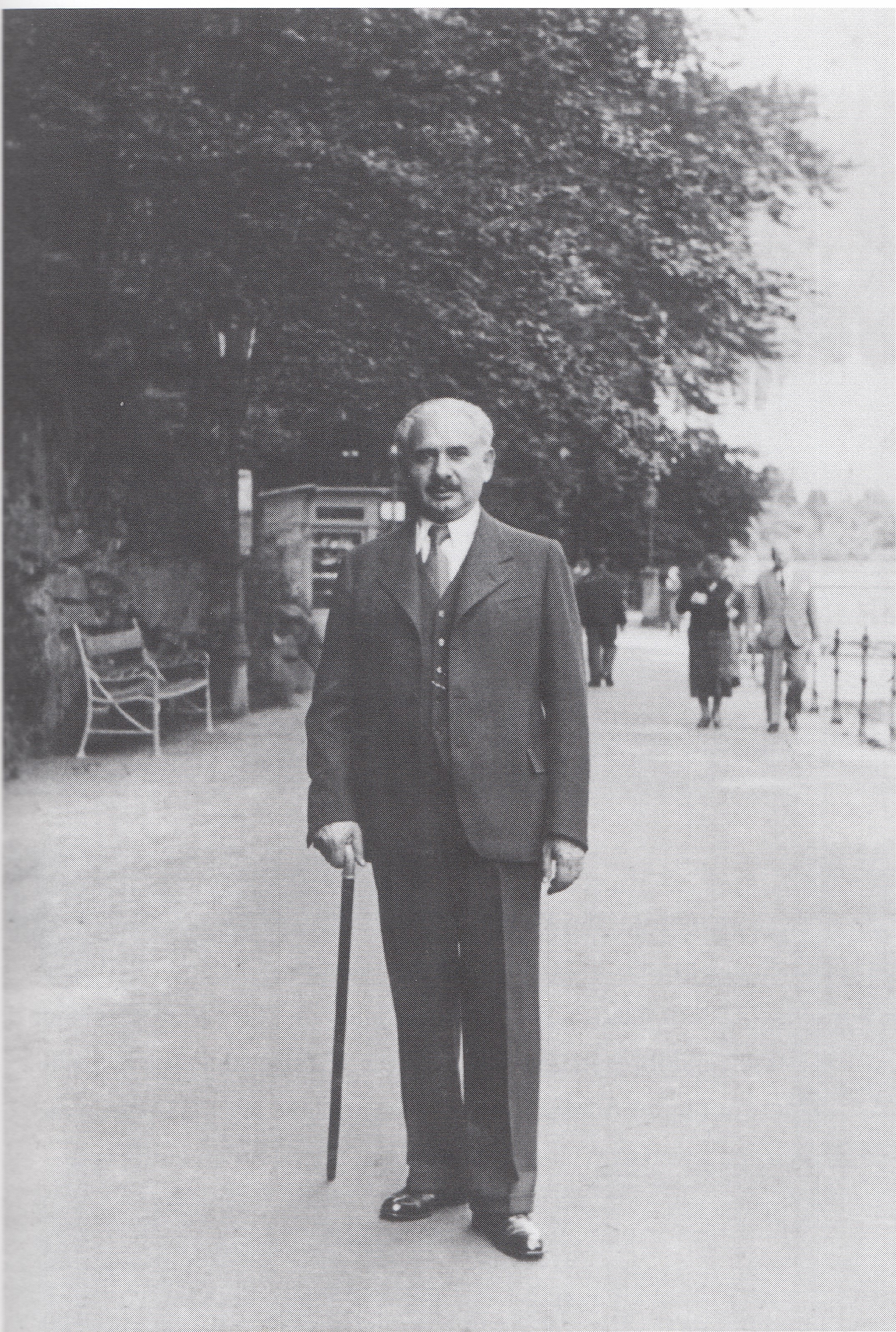

Berthold Storfer

(Cernowitz 1880 – Auschwitz 1944): The Jewish Rescuer of Jews

Adolf Eichmann’s visit to Auschwitz

Some concentration camp stories seem so grotesque as to sound almost implausible – this is one of them. One of the main architects of the deportations of European Jews to the extermination sites, Adolf Eichmann, paid a visit to the Jewish prisoner Berthold Storfer at Auschwitz concentration camp. The two were acquainted from Eichmann’s time in Vienna, when he had set up the Central Office for Jewish Emigration to organise the expulsions. Storfer had already offered his services to the SS at the beginning of the Nazi period to support the escape – i.e. the expulsion – of the Jews. The former top manager apparently also had the ear of the SS because of his knowledge of Eastern Europe, and the “Committee for Jewish Overseas Transports” that he ran became a driving force in planning the transports to Palestine, the largely illegal escape to British-controlled Palestine. At the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann in Israel, the latter claimed that he had had Storfer brought to him at Auschwitz: “Yes, my dear good fellow, what bad luck have we had?”, he asked Storfer. He was alluding to the fact that Storfer had gone into hiding in Vienna in 1943 for fear of deportation – a “stupid thing to do” according to Eichmann. Hanna Arendt observed the trial against Eichmann in which he made this statement. In her book Eichmann in Jerusalem. Ein Bericht von der Banalität des Bösen (“Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil”), Arendt asked, in view of the statements about Storfer, whether Eichmann was a classic case of pathological mendacity coupled with abysmal stupidity or just ordinary criminal obduracy.

The historian Gabriele Anderl estimates that Storfer facilitated the rescue of 9,096 Jews. In February 1939 Eichmann instructed him to organise the illegal transports to Palestine, and in March 1940 the SS put him in charge of transports from the so-called “Altreich” and the “Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia”. He thus became the key Jewish organiser of this escape route. His role was not without controversy, since Zionist organisations also oversaw legal and illegal transports to Palestine and were motivated in their selection by the political orientation of those they rescued, i.e. they preferred young, healthy, Zionist-leaning people. Organising the transports was elaborate and nerve-wracking in the face of the ongoing war. There was the delicate issue of selecting people for the transport, the procurement of foreign currency and ships, supplies for the fugitives and much more. In addition, there was the problem of illegal immigration. In October 1940, three ships with refugees left the Romanian Danube port of Tulcea. In Palestine, the British authorities picked up the refugees, seeking to prevent them from immigrating illegally. The British put the refugees on board a ship called Patria to be deported to Mauritius. On 25 November 1940, as passengers were being transferred from the last of the three ships, an explosion occurred. The attack, carried out by the armed Zionist underground organisation Haganah, inadvertently caused the ship to sink rapidly, killing 267 people. Those rescued were then allowed to remain in Palestine; those still aboard the third ship were interned in Mauritius.

Eichmann claimed at the trial that Storfer had asked him during their Auschwitz encounter to see to it that he would no longer have to work, but this was refused by the Auschwitz Commandant, Rudolf Höß. However, he, Eichmann, could have arranged for him to be given easier work. The phrase “my dear good fellow” is indicative of the feigned politeness of Eichmann, the SS man. Whether these words were ever actually uttered remains to be seen. A few weeks after Eichmann’s visit Storfer was dead. As a holder of secrets, he had barely had a chance at survival anyway.

Literature

Gabriele Anderl, 9096 Leben. Der unbekannte Judenretter Berthold Storfer, Berlin 2012.